In an earlier phase of my life, I worked as a professional astronomer, and I've loved space and astronomy since before I could pronounce the words. So naturally, I've gotten a lot of personal pleasure from the free software astronomy tools that are included in my Debian GNU/Linux system. But ironically, I haven't written about them much. Recently, though, I was asked a question which I used KStars to answer, so this is a good chance to talk about how to use it.

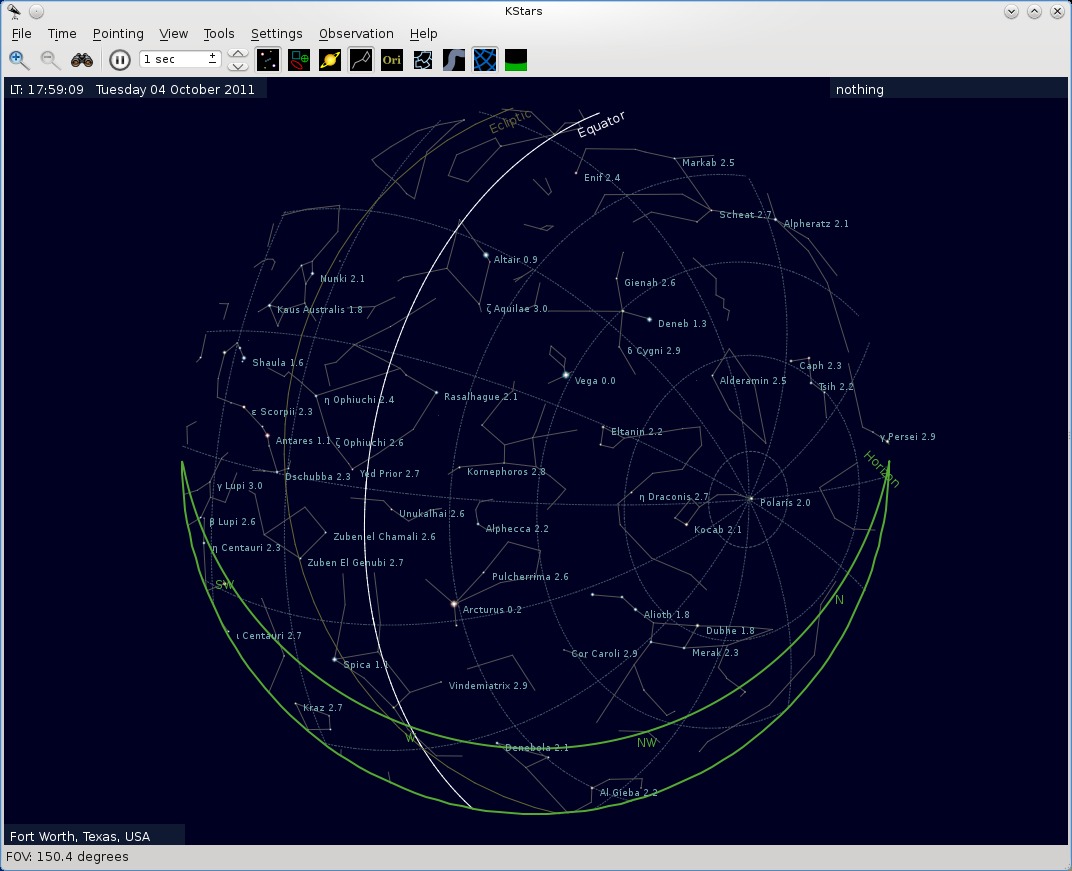

KStars is a "planetarium" software for KDE. This means that it is designed to show you what the night sky will look like on a particular night at a particular time in a particular location on the Earth. As you probably know, we are living on a rotating spherical Earth, tilted about 23 degrees from the plane of its orbit around the Sun. And of course, the other seven major planets, five dwarf planets, and zillion minor planets in our solar system are doing much the same.

With all of that motion, it's relatively complicated to keep track of where everything will be relative to your position. Working it out in your head or on paper is not too productive (and I have a bad habit of dropping minus signs which has gotten me into trouble on more than one occasion), so this is an ideal job for a computer.

Recently, a friend of mine who is an editor for a science-fiction publisher and a space activist asked me an interesting question, which I paraphrase: "Of the stars visible to the naked eye in the early evening in Summer (from a viewing location near Dallas, Texas), which is the closest (not the brightest)?" I don't really know why he wanted to know this. Perhaps he anticipates using the information in a public lecture or at a star party. But I was intrigued by the challenge.

The Distances of Stars

You might wonder how it is that we even know the distances to the stars. Like many things in science, it's not easy to work out, but there is a way.

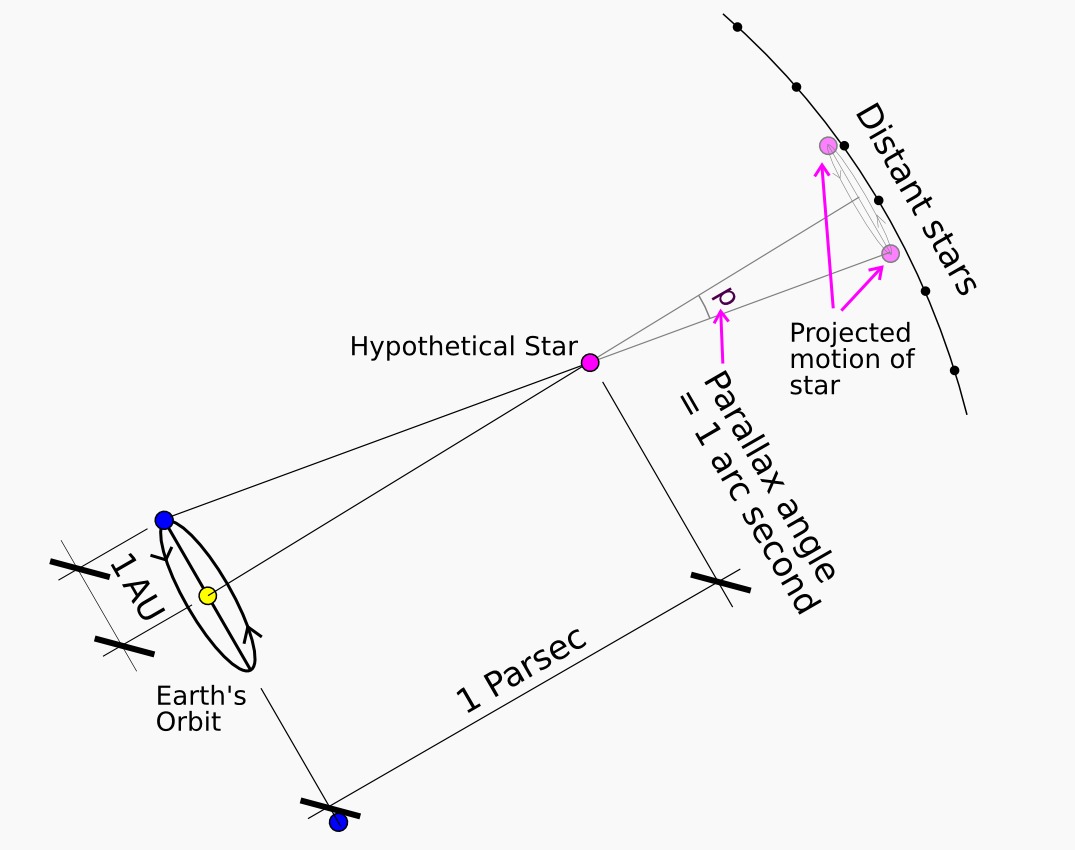

As long as every large telescope we have available is located on (or even orbiting) the Earth, we have a severe depth-perception problem with the stars. Even the nearest are so very far away that there isn't enough parallax available to us to accurately compute their distances -- unless we employ some very clever techniques. Which of course, we do. For a few hundred of the nearest stars, it's possible to get a direct measurement of their distance by using the Earth's orbit around the Sun as a stereoscopic baseline.

For a few hundred of the nearest stars, it's possible to get a direct measurement of their distance by using the Earth's orbit around the Sun as a stereoscopic baseline

Once you subtract out other effects, measurements from different points along the orbit result in slightly different projected positions of the stars. This apparent motion is called "parallax". For a dozen or so of the very nearest stars, it is a sizable fraction of an arcsecond (the parallax for Alpha Centauri is about 0.75 arcsecond). Of course, the parallax gets smaller as the distance increases.

For a hypothetical star with a parallax ellipse exactly one arcsecond across (though none are actually that close), the distance would be called "one parallax-second" or "one parsec" -- a unit of interstellar distance that is preferred by professional astronomers. A parsec is about 3.26 "light years" -- a more popular unit outside of professional astronomy, which is simply how far light will travel in one Earth year.

Practical measurements for astronomical parallax have required extremely careful measurements. The best to date are those provided by the ESA's Hipparcos orbiting telescope. Hipparcos pushed the limit down to about 0.001" ("one milli-arcsecond"), which means it could measure parallax to about a 10% error at 100 parsecs.

There are ways of estimating distances for further objects, using the so-called astronomical "distance ladder", but parallax distances are sufficient to cover my near-stars problem.

Enter KStars

So, getting back to my friend's question -- I did what I usually do when I want to know where something is in the sky, I started up KStars. Fortunately, one of the nice features of KStars is that it allows rapid access to its database information about the stars it displays, and distance is one of the fields.

So now all I have to do is to figure out which stars would be visible and check their distances. So that's what I did.

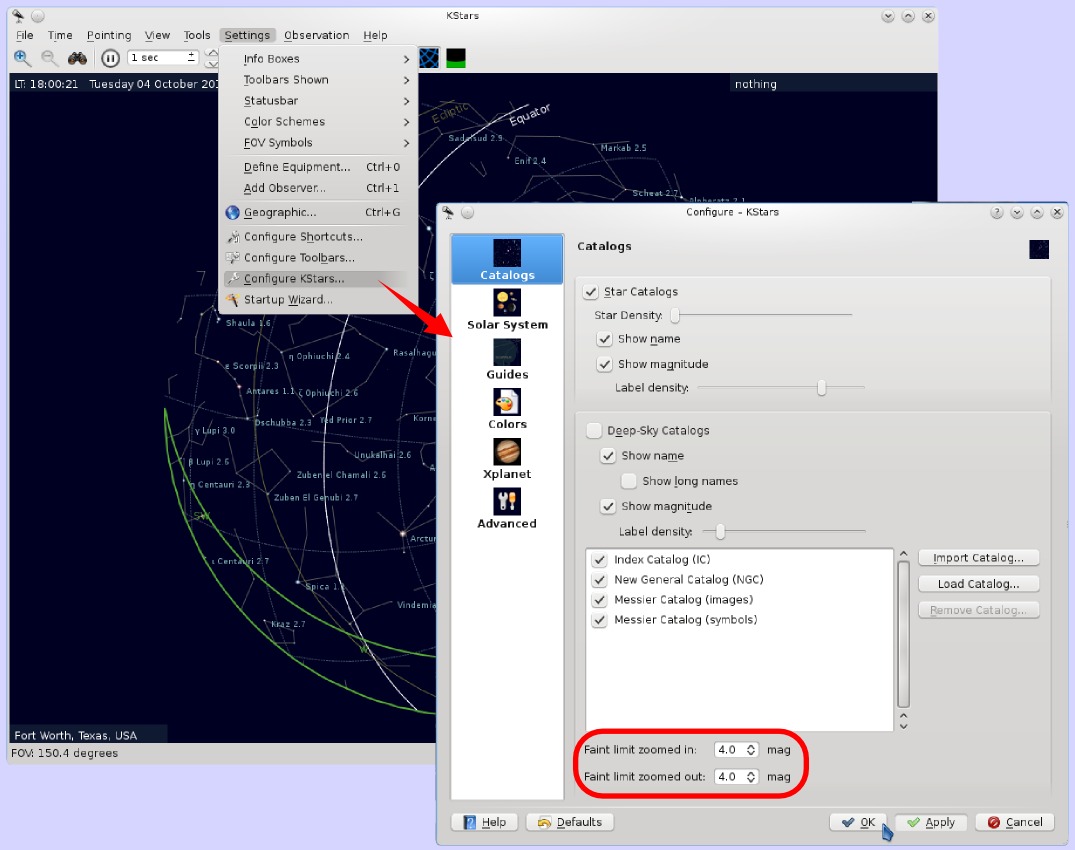

Step 1 - Set the Magnitude Limit

My first step was to limit the search to stars that would be clearly visible. The books usually say that's about magnitude 5 or even 6, but that's under very good conditions that most people -- certainly most city-dwellers won't have easy access to. I chose magnitude 4, because this is the brightness of one of the dimmer stars in Cygnus that I can almost always pick out on a clear night. Even so, considering that my friend lives in Dallas, that might be pushing it a little -- maybe I should have used 3.

To set this, you have to go to the Settings->Configure KStars dialog and adjust the magnitude limits. Technically, there are two different limits, one for when you're zoomed out and one for when you're zoomed in. I'm not sure what it does in the middle -- split the difference, probably. Anyway, I just set both of them to 4.0.

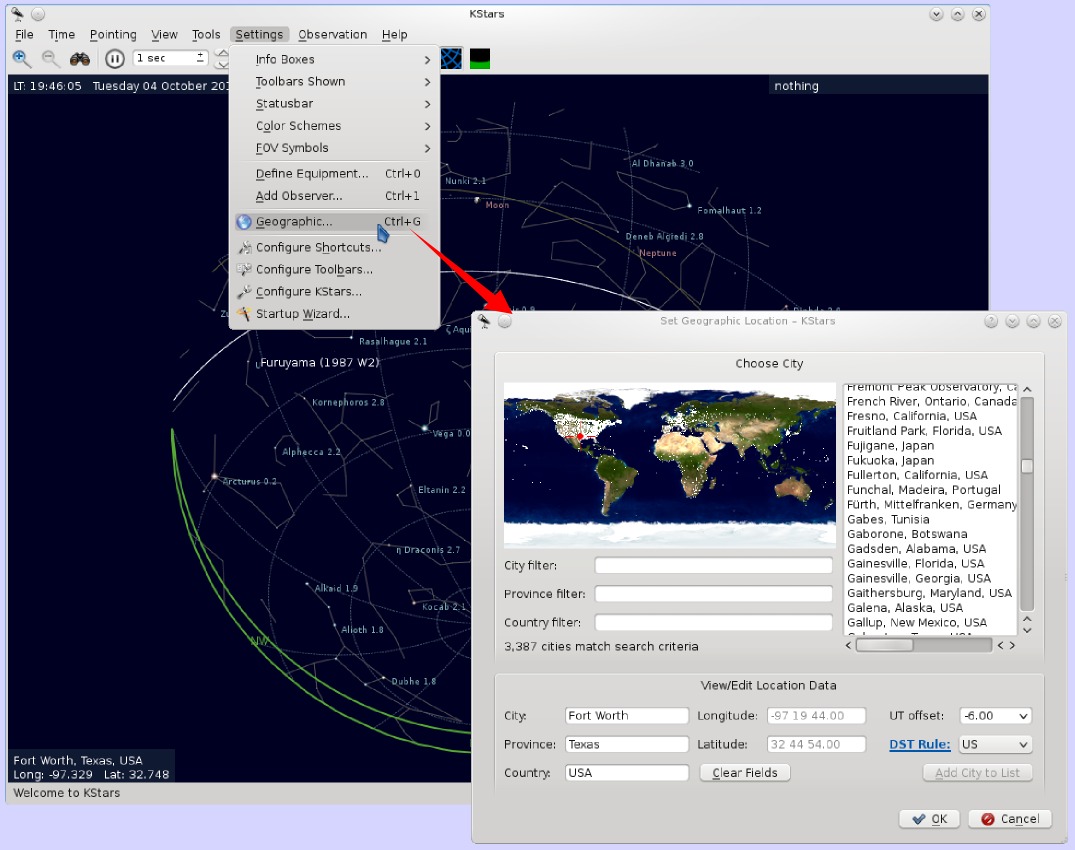

Step 2 - Set the Observer's Location

I actually didn't have to do this, because my friend lives close enough to me that we see pretty much the same stars, but in general, you do need to set the coordinates for your observing location.

Go to Settings->Geographic... to find your location. The easiest way is probably by selecting a nearby city from the database that KStars provides, although you can also enter coordinates directly.

Step 3 - Set the Time and Date

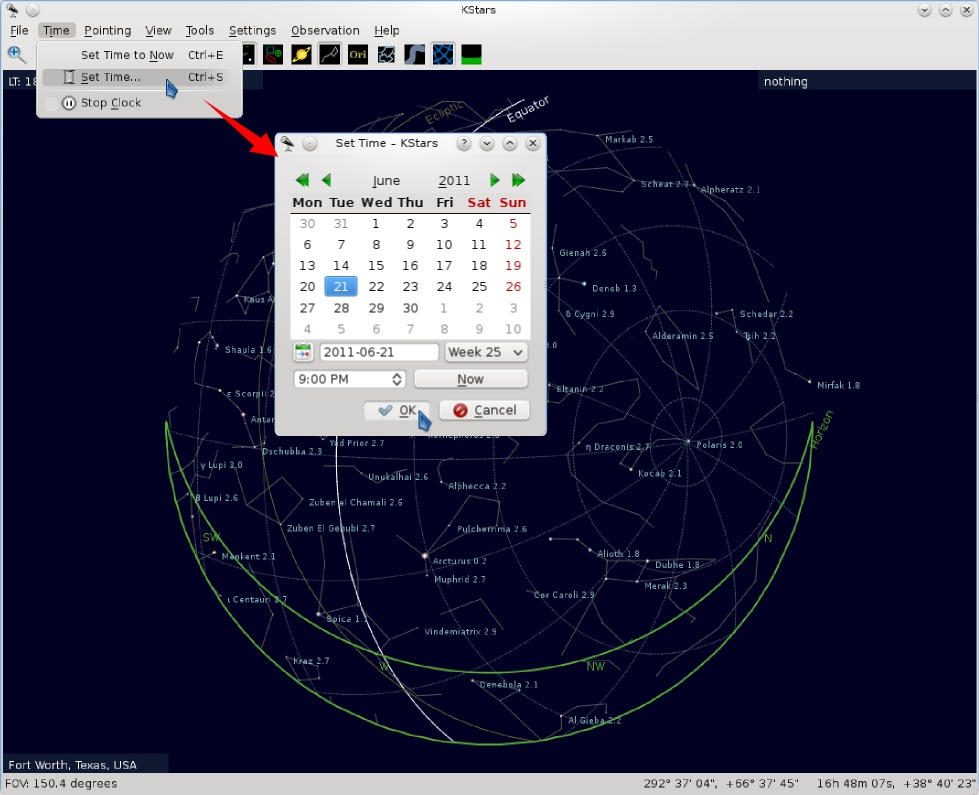

The next step is to pick the observing time. There's a separate menu for Time, because it's used frequently, go to Time->Set Time... and you'll get a dialog box with a calendar for setting the date and a time widget.

The time widget is a little weird, in my opinion, because it won't just let you type in the time you want. Instead, I have to select the hours and minutes fields separately then click the arrows (or use my mouse's scroll wheel) to set the time. Odd, but it works.

Once you set the time, it will start ticking forward in real time by default. This won't really hurt anything, but if you want to be a purist, you can stop it by checking the "Stop Clock" option in the time menu.

Step 4 - Lookup Data on Stars

At this point, I now have a window showing me what the sky will look like for my friend, observing in the middle of the Summer (in fact, I've selected a time very close to the Summer solstice, just after sunset). I suppose, it would be more accurate to have picked next year's, since my friend will not be time-traveling, but the year is pretty much immaterial for this search.

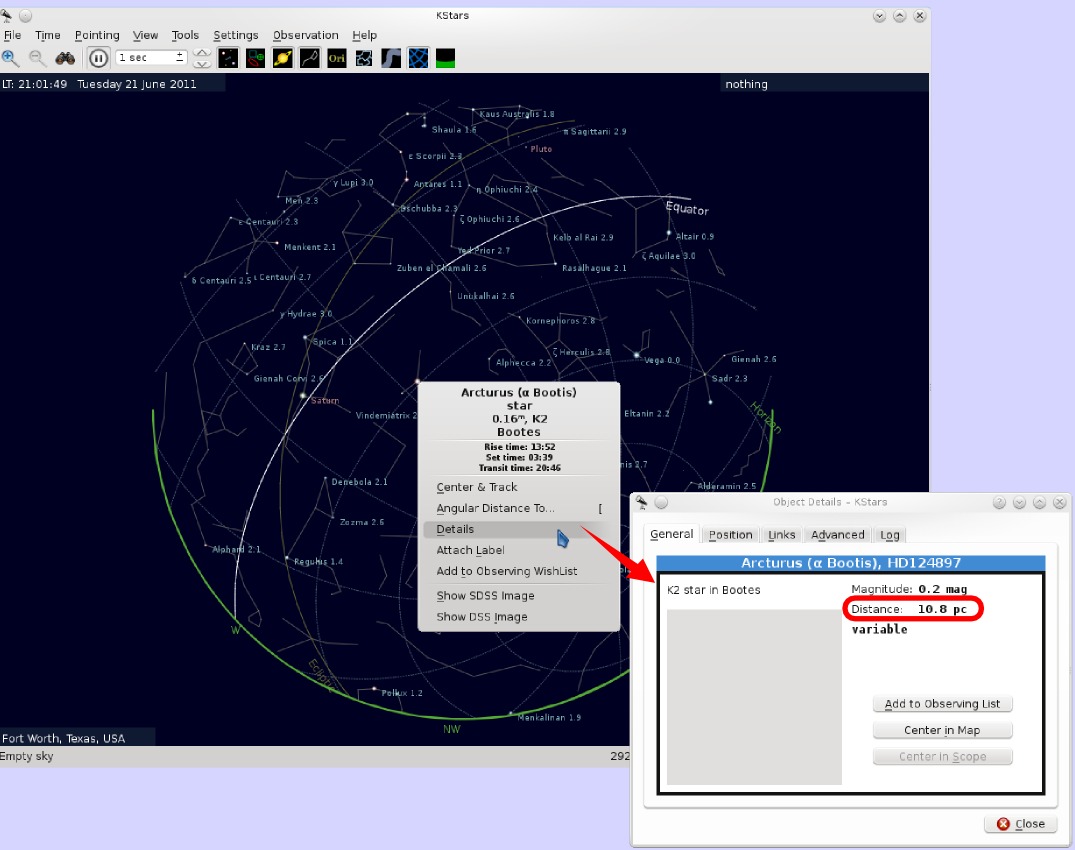

Now, the number of stars is fairly manageable, and I just search for the ones I think are possible, and I click on them with the mouse. This brings up a brief description, and by clicking on details, I will get the rest of the database record, which includes the distance in parsecs.

A few searches like this reveals that the answer is probably Altair, which, at magnitude 0.9 is also one of the brightest stars up at this time, so that should be no problem for my friend to point out even in the city. Altair is an A7 star (which means it's somewhat brighter and hotter than our Sun) about 4.95pc or just over 16 light years away.

Licensing Notice

This work may be distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License, version 3.0, with attribution to "Terry Hancock, first published in Free Software Magazine". Illustrations and modifications to illustrations are under the same license and attribution, except as noted in their captions (all images in this article are CC By-SA 3.0 compatible).