Some weeks ago I (Marco) was looking for new things to learn in Perl. I took a look at my library and reviewed the titles of the books I read less, and after some consideration found two topics: GUIs and threads. But since I hate the “hello world” kind of programs, I decided to start this exploration of the (for me) unknown parts of Perl with a somewhat meaningful application: a chat.

The chat project

This article has downloads!

When I do this sort of thing, I like to discuss my ideas with other people, and that’s where Stefano always comes in. Stefano is a Java programmer, and knows very well how to deal with GUIs and threads. We talked about the project, and he gave me some structural advice for the program. Besides, we thought, doing things with a standard protocol like HTTP would greatly simplify the design, since there were a lot of ready-to-use modules on the CPAN to handle it, and it would help to make the application interoperable.

Essentially, I had two sources from which to study Perl threads: the chapter about them in the “Camel Book”, that is “Programming Perl” by Wall, Christiansen and Orwant; and the “perlthrtut” document, which is bundled with all recent Perl distributions. Other information was spread across the documentation of the threads, threads::shared and Thread::Queue modules.

It’s a peer-to-peer application: you run it specifying the address and port you want to contact another instance of the application, and you are given a GUI where you can type text and read replies

After experimenting a bit with the new things that I was learning, I decided that it was time to go for the real thing. I then picked up the “Learning Perl/tk” book, which I had read a while ago but never applied in practice, and reviewed those parts that allowed me to create a simple interface: a window with a big textbox to display the conversation in, a text field for the input, and a button to submit the typed text to the chat application.

The design of the application was fairly simple. First, it’s a peer-to-peer application: you run it specifying the address and port you want to contact another instance of the application, and you are given a GUI where you can type text and read replies (a bit like what happens with the old UN*X talk application that you may be familiar with). The communication takes place by means of POST HTTP connections: to send a message to your peer, you submit a POST request to the other peer at the /message URI; the POST request contains two variables: name, set to your nickname, and message, which contains the message to be sent. To receive a message, the application acts as an HTTP server that handles POST requests to the / message URI, formatted as just described above.

The problem with threads

Modern applications perform many operations at the same time. Internet browsers, for example, need to show update information about internal processing while managing multiple connections. Word processors have to assure fast response to user input and, if needed, safely create snapshots of current state for unexpected crashes. Internet browsers and word processors (and multimedia players, games, instant messengers...) are examples of applications that have multithreading capabilities.

Multithreading refers to the ability of an application to divide execution in threads that run simultaneously (or, at least, they appear to). While in the multiprocess model each process runs in its own private (and hence safe) environment, threads share the same memory area.

Memory sharing requires from the developer an extra effort to manage concurrent access to the same location. Moreover, a thread may have to wait for another thread to complete before continuing with its execution.

Data structures and classes are called thread-safe when they are able to serialize concurrent access to their internal data. They provide mechanisms to assure that, in a certain time slice, only one thread has read and write access to the shared memory. Vice-versa, non thread-safe structures may have unpredictable, time-dependent behaviour and it’s the programmer’s responsibility to arbitrate data access from concurrent threads. Therefore, depending on the language and library in use, multithreading programming becomes easier or more complex, easy to be adopted or harder to get running. At the same time, libraries can be totally or partially thread-safe, leaving it up to the developer to write their own safe structures.

Depending on the language and library in use, multithreading programming becomes easier or more complex, easy to be adopted or harder to get running

The multithreading approach simplifies the design and implementation of applications in all those cases where they can be described as a set of co-ordinated, parallel tasks. There are even cases when programming in a non-multithreaded model is not an option. In the Java2 Micro Edition runtime, for example, you are required to manage network connections using a separate thread for communication routines.

The problem with Perl threads

Besides all of the caveats that are typical of threads programming, Perl adds some more that are specific to the language. For example, in recent versions of Perl, no data is shared by default between threads, which means that you must specify what you want to share explicitly. Besides, if you want to share objects then you know that you are going to run into trouble, and if you want to share objects that contain globs in their data structures (that means, for example, objects that contain filehandles and sockets) you are going to run into big trouble! This forces everybody that is going to design a threaded Perl application using objects to be very careful, or to use one of the alternatives around, like POE, and give up with Perl threads.

Oh and instead, a Thread::Queue object can be shared between threads, but no: you can’t share objects using it!

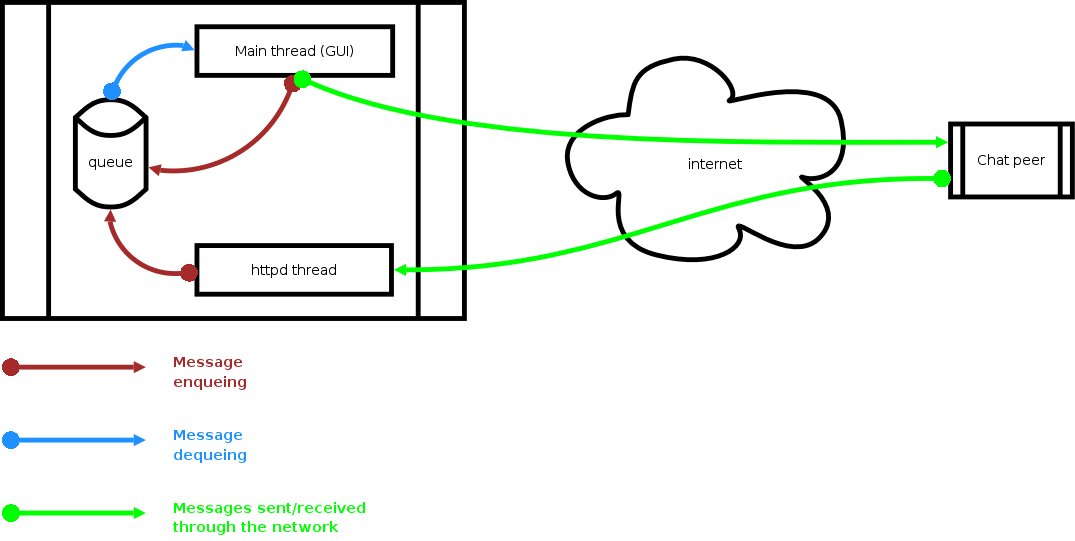

These problems probably led to the misbelief that Tk GUIs and threads don’t work nicely together. However they do, as long as you don’t try to share GUI objects around. The application we are going to describe does just that. Essentially, there is a main thread where the GUI and its objects live, and a second httpd thread that waits for incoming messages. When a new message is received, the httpd thread enqueues it for the GUI to read and display it in the chat window. In a similar fashion, when a message is sent to the peer, it is also queued and shows up in the chat window, so that there is only one way to update it. The GUI objects in the main thread and the httpd object in the other thread don’t need to know anything about each other: when the httpd has messages to export outside, it queues them; in turn, the GUI checks regularly if there are any messages waiting in the queue and acts accordingly. The GUI doesn’t need to know where the messages come from, and it avoids the complications of multiple threads acting on the chat textbox simultaneously by having just a subroutine that reads from the queue and updates it.

The Perl application

For this application, I used many modules. Some of them, like threads, threads::shared, Tk and Thread::Queue to name a few, are indispensable; some are just useful and may well be considered overkill, but they had at least one interesting feature that I wanted to use: AppConfig, CGI and Time::HiRes fall into this category; others were just convenient to get the job done: HTTP::Daemon and HTTP::Status for the server side and LWP::UserAgent for the client side. You may well want to trim down the application and its resource usage by eliminating the need for some of them: feel free to do anything you like with it, it’s free software!

You can run the application using its built-in default values; in that case, it will connect to localhost, port 1080 and listen on the very same port, so that you end up in talking to yourself. If you want to try something a bit more interesting, try to connect to another instance of the chat by passing some meaningful value to the -peerhost, -peerport, -localport command-line parameters. For example, if you want to play with two windows just run something like this:

bronto@marmotta:$ perl chath.pl -peerport 1081 -mynick bronto &

bronto@marmotta:$ perl chath.pl -localport 1081 -mynick maroon &

That will create two windows that talk to each other. Note that you can let the application guess your username or you can whisper one in its ear by means of the -mynick option.

After setting up the required infrastructure (like the queue for exchanging messages and the user agent object to send the messages) we start the httpd thread and let it run free:

my $httpdt = threads->new(\&httpd) ;

$httpdt->detach ;

The internals of the thread, that is the httpd subroutine, are quite simple: it tries to create an HTTP::Daemon object and sits there awaiting for incoming connection; the accept() call timeouts every ten seconds, so that it can check if the main thread requested it to exit. When a new connection is accepted, it is checked for safety (it must be a POST request to the /message URL), the message is decoded by means of the CGI module and the incoming message is queued.

Back to the main thread, all components of the GUI are created, configured and finally packed into the main window. Just before running the MainLoop of the GUI and letting Tk go, we also set up the chat textbox so that it looks for updates every 300 milliseconds (that is: 3 tenths of second):

$tbox->repeat(300,\&update_chat_window) ;

MainLoop ;

Everything from this point on runs smoothly. Each time a message is sent or received, it is also queued; every 300 milliseconds, the GUI runs the update_chat_window and checks if it has any messages to dequeue and print.

This lasts until you close the main window. When you do it, the MainLoop ends, and the main thread follows its race down the program: it updates the shared variable $keep_running, signalling the httpd thread to terminate as soon as possible, and waits for a while. If, after ten seconds, the httpd thread is still running, the main thread raises an exception and the whole application terminates (well, hopefully!).

Java Threads

Java offers a good support for multithreading programming. Although it is not the best on the market, it allows developers to write multithreading code with little effort. Threads are “embedded” in the Java language and the standard class library. The “Tiger” (codename for the last JDK, version 5.0) provides enhanced support for concurrent programming. Basically, writing a thread in Java means either extending the standard Thread class or implementing the Runnable interface and assigning it to a Thread. Usually, you have to use the second approach when your threaded class needs to extend an existing one: since Java does not support multiple inheritance, implementing the Runnable interface is mandatory. Whatever we choose to do, the core of the thread lives in the run() method. Java provides constructs to synchronize concurrent data access. The wait-notify construct used in the chat example allows the developer to synchronize thread’s routine: the thread is paused (wait()) when a message has been sent and it is resumed (notify()) when a new message is ready to be sent.

The Java application

The chat example described above uses threads to manage incoming messages. In the Java example we will see how to use thread effectively to implement message dispatching.

Java offers a good support for multithreading programming. Although it is not the best on the market, it allows developers to write multithreading code with little effort

Before exploring it, let’s have a look at server-side. The Java platform provides the Servlet application model, which is state-of-the-art technology for business services. That’s an overkill approach for our needs anyway, so we chose the Simple project’s web server. It is both a powerful (and actually simple!) web server and a Servlet container that can be easily embedded into other applications.

For web server functionalities, Simple architecture requires you to extend the BasicService class. Our subclass has just to implement the process() method, which receives request and response objects used to deal with current connection. Simple manages its own threads for incoming connection, so that multithreading is hidden within the library! We have only to deal with outgoing messages.

For the client part, we can choose between three different implementations: blocking, multithreaded and singlethreaded. We wrote the doSend() method, which receives the String being sent to the remote peer. doSend() obtains an HttpURLConnection instance from the URL factory, sets the connection method (POST), encodes all parameters and, finally, writes the data through the connection and closes it.

doSend() is a blocking method: it does not return until data has been transferred and connection has been closed. Therefore, if we don’t want it to block the whole interface, we have to wrap it around with a multithreaded method. That’s why we have doSyncSend, doMultiThreadSend, and doSingleThreadSend().

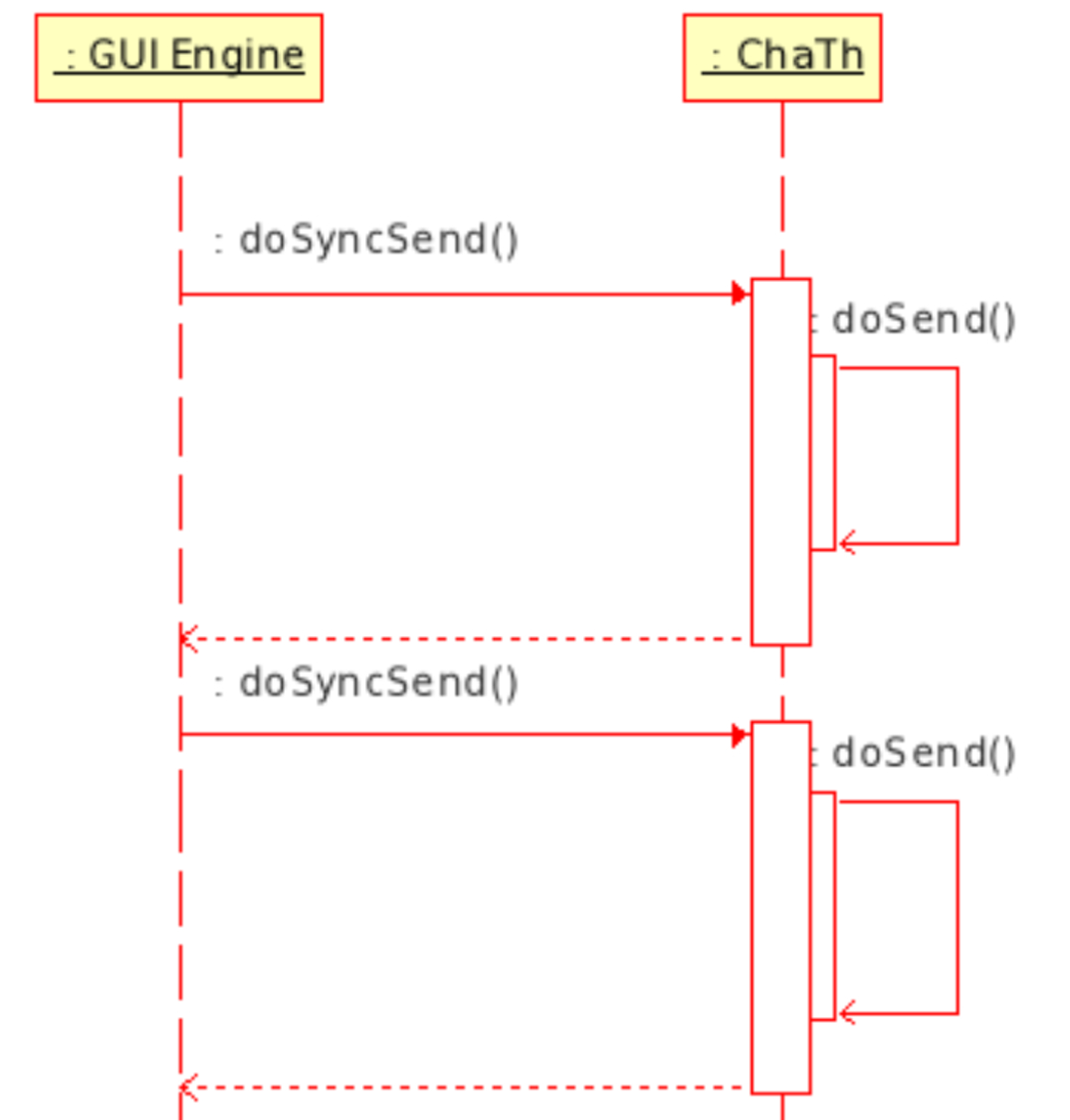

The first approach is very similar to the Perl solution: when the user clicks on the button, doSyncSend() just invokes doSend(), therefore the GUI is blocked until doSyncSend() returns. It is not critical for our application, but you must be aware that the GUI will not be updated until message has been actually sent.

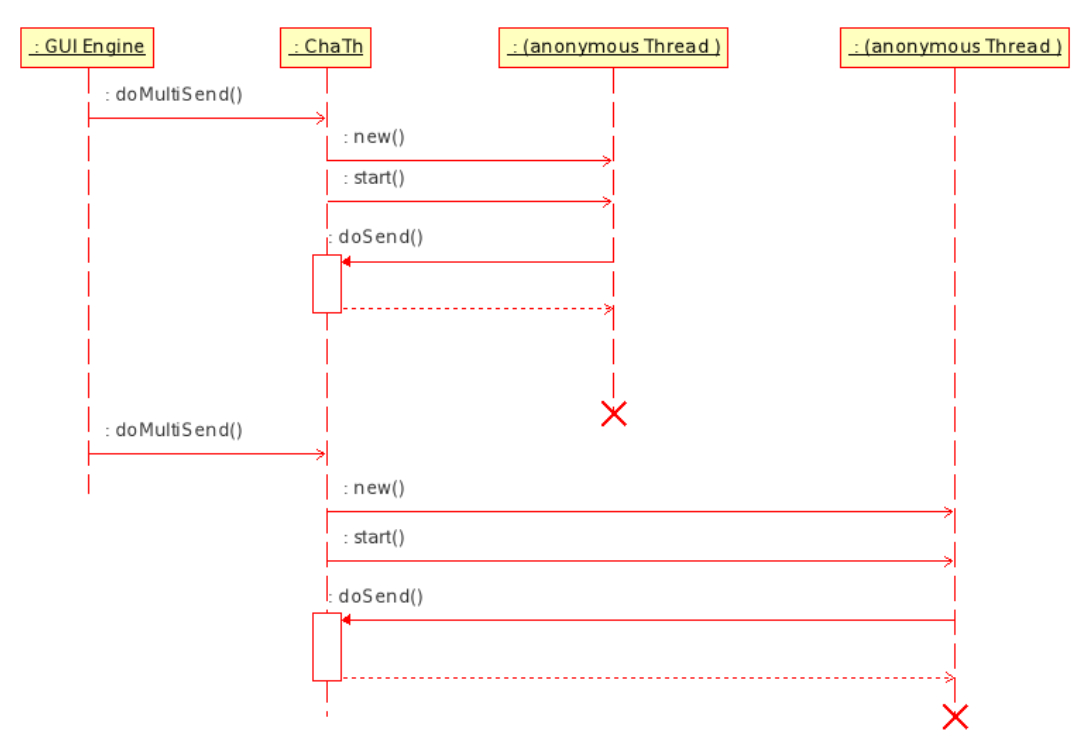

The second approach, doMultiThreadSend() method defines and instantiates an inner anonymous class which extends standard Thread. Its run() method invokes the doSend() method. However, since it is being executed in a separate thread, doMultiThreadSend() returns immediately, so that the GUI won’t block. In short: to avoid GUI blocking, we create a multithreaded sender procedure where a new thread is created every time the user needs to send a message.

Creating and destroying threads could be very resource consuming. It’s a suitable approach for our simple chat, but its usage is generally discouraged for more complex applications

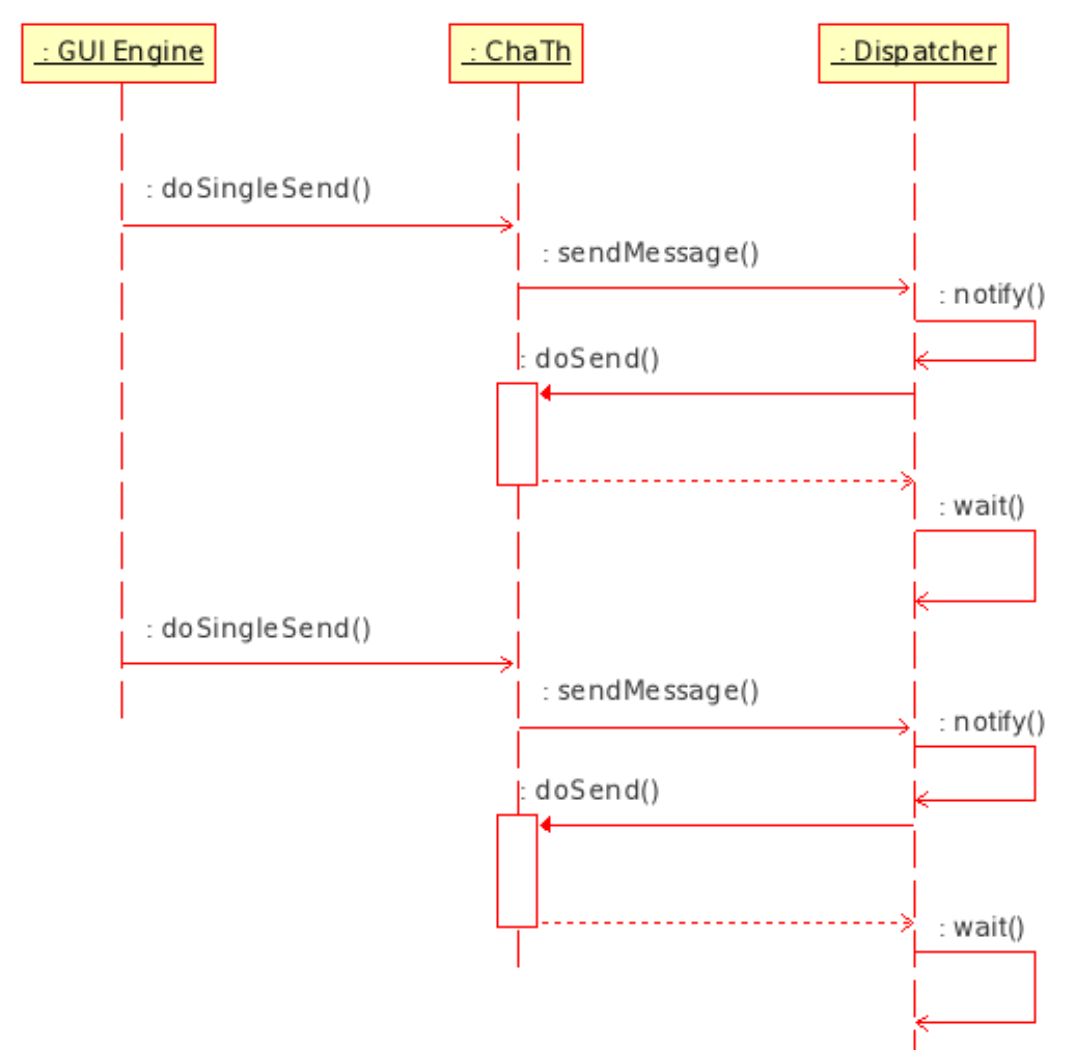

Creating and destroying threads could be very resource consuming. It’s a suitable approach for our simple chat, but its usage is generally discouraged for more complex applications. That’s why we implemented a third approach, the most popular in real-world applications. A separate, single thread (or a thread pool) is used to manage outgoing messages. Such a thread maintains a queue of messages and dispatches them serially.

In our example, the Dispatcher class receives just one outgoing message at a time using a wait-notify scheme. Delivery of the message takes place inside the run() method, which sends a message and then stops in a wait(); when a new message is provided by the send() method, it notifies the object which unblocks run().

Conclusion

We have just scratched the surface: designing and implementing a multithreaded application requires deeper knowledge of both concurrent programming paradigms and programming techniques of the language in use. In the specific case of Perl, the implementation of threads is far from being satisfactory and production-ready, but as with other things in the language, you can get used to them and prepare for when Perl 6 finally comes out.

Bibliography

Wall, Christiansen, Orwant “Programming Perl”, 3rd Edition, O’Reilly and Associates, 2000

Walsh, Nancy “Learning Perl/Tk”, O’Reilly and Associates, 1999

Lea “Concurrent Programming in Java: Design Principles and Patterns”, Addison-Wesley 1999

Harold “Java Network Programming”, 3rd Edition, O’Reilly and Associates, October 2004