Have you ever felt that warm fuzzy feeling of knowing that your code is error-free and complies with the latest standards? In terms of programming skill, web authors are too-often seen as the bottom of the barrel (you will notice I didn't call them 'web programmers') due to the apparent forgiveness and limitations of the platform. However, they are required to cover a large array of programming expertise and, even worse, they must ensure that their code runs the same on various platforms–something "real" programmers consider a challenge.

The "bottom of the barrel" indeed!

During the first browser war, from 1997 to 2001, being a web coder was interesting, with the gap between Internet Explorer (IE) 4 and Netscape Navigator 4. The former used "advanced" CSS (how things have changed!) while the latter had interesting scripting capabilities (but its frequent releases were so quirky that they discouraged developers from using them).

But when Netscape was sidelined, web authors were required to write for a single platform (IE) which had a proprietary model–and this sad state of affairs lasted for half a decade. During that time, web coding required you to know very little: Visual Studio (or Frontpage, or Dreamweaver) and the twisted view of the Internet that IE 5/6 gave you.

Recently though, due to the rise of "alternative" browsers (such as KHTML/Webkit-based Safari, Mozilla Firefox, and Opera), writing code only for IE would make any website automatically loose 20% (or more) of the market; and this trend isn't reversing (even IE, with version 7, is getting slightly more standards-compliant). So web authors must change their habits and code for more platforms. And what's common between most of these alternatives? Conformance with standards.

Which, authors find out, are quite a challenge to use correctly.

Now, some web authors may try to keep creating "tag soup". It is perfectly possible to output atrocious code that all current rendering engines will treat the same way–or choke on similarly. However, one may very soon find out that actually creating "good" code is much less of a hassle than tinkering with "tag soup" is.

It is perfectly possible to output atrocious code that all current rendering engines will treat the same way–or choke on similarly

Creating good mark-up

The basis of a web page still is hypertext mark-up language (HTML). It has seen several variations, with HTML 4.01 and XHTML 1.0 (each further divided into Transitional, Frameset, and Strict versions) being the most interesting to look at. The main difference between these two is that XHTML 1.0 is equivalent in functionality to HTML 4, but makes use of XML syntax instead of HTML.

Moreover, while HTML 4.01 doesn't care about the case of tags and parameters, XHTML is case sensitive: all tags and parameters must be in lowercase. In the present document, when talking about a specific tag, I will write it uppercase for easier reading. However, they will be written in lowercase inside code samples.

The three sub-divisions are the same for both languages:

-

Transitional takes HTML 3.2 (the Frankenstein's Monster of web specifications) and tries to give it some order: several duplicate functionalities are removed, and some parameters are unified. It is also the first HTML specification that allows you to build a standardized Document Object Model (DOM).

-

Frameset removes most of what made HTML 3.2 a Frankenstein language: anything that is geared towards making HTML something other than a mark-up language was removed (specific style options, tags that required actions from the browser, etc.), apart from frames. Those used to be useful for early "dynamic" websites, and were kept for a time.

-

Strict is similar to Frameset, but removes frames from the specifications. Indeed, they are actually redundant and harmful since frames break navigation models and can be advantageously replaced with more generic OBJECT tags (except that those are still not correctly supported under IE 7).

Strict versions of XHTML and HTML are the easiest to learn, and the most similar–but I would personally recommend the use of XHTML 1.0 Strict for authoring your pages because several web browsers are, now, able to notice incorrect code and report it directly.

Once you are done, you'll be better off (at least for now) with HTML 4.01 Strict–which requires very little in terms of modification over XHTML 1.0 to validate: indeed, making XHTML code into valid HTML code merely requires slashes (/) to be removed from self-contained tags (like BR), and image maps (rarely used nowadays) to change their syntax slightly (and this was, actually, an error when establishing XHTML syntax–most browsers today use the HTML 4.0 syntax for image maps on XHTML 1.0 documents anyway).

For example, while in HTML 4.01 a horizontal ruler (HR) could be written as <HR> or <hr>, in XHTML 1.0 it must be written as <hr/> (or <hr />; note that extra space, so that browsers like IE 4 or Netscape 4 can still understand it).

Validation, why it will help you

What is validation? Well, it is ensuring that no tags are used that don't belong into the document type. Here follow a few notable examples:

-

FRAME is no longer allowed in Strict documents; this tag allowed you to load another HTML document inside a frame. It wouldn't appear in the browser's history, and implied a graphical representation. The OBJECT tag is more versatile, as it can open HTML documents, but also images, movies, and applets. It can also be nested so as to provide fall-back content. For example, if a browser can't open a movie; it might try to open a Flash applet; and if Flash is not supported, it might open an animated SVG; and if that's not supported, then it might open an animated GIF, and so on.

-

MARQUEE is no longer allowed in Strict documents; this tag allowed you to put a lot of content and have it scroll inside a block element. Parameters defined how fast the scrolling went and in what direction. This required HTML to describe actions, which is contrary to the format's purpose. It can be replaced with CSS and JavaScript.

-

The

targetparameter inside anchors (A) is no longer valid in XHTML 1.0: instead, you must userel(which defines the relationship of the anchor'shrefdesignated document in relation with the current document). Opening a new window must be made specifically through JavaScript, makingtarget="_blank"illegal. However, due to its heavy use,targetwill remain part of HTML 5.

To generalize, elements that entail an action from the browser or that have more efficient alternatives are being phased out of HTML.

Elements that entail an action from the browser or that have more efficient alternatives are being phased out of HTML

HTML 5, which is in the planning stage, will use HTML 4.01 Strict as a basis. Thus, it is worth your while learning about HTML 4.01 Strict. But this is only one advantage of validation. Next comes proper tag chaining and proper tag nesting.

What's wrong with badly nested tags? Well, here's an example:

<b><i>some stuff</b>

some other stuff</i>.

The correct form would be:

<i><b>some stuff</b>

some other stuff</i>

Nothing too hard! However, you may sometimes want text styled like this:

<b>bold text

<i>italicized and bold text</b>

italicized text</i>

And what's wrong here? Well, it is very troublesome.

The DOM is supposed to be a tree. This means that an element can contain several elements, but elements can't overlap. In the example used above, closing the bold tag should make the italic tag automatically close (and the closing tag is, thus, a coding error), but since italics must be explicitly closed, we have here two coding errors: an unclosed italic tag, and an unexpected italic closure.

How do browsers deal with this wrong mark-up?

-

Mozilla Firefox/Gecko considers that bold and italics are closed at the same time on a DOM level, but may apply CSS styles until it reaches the italic closure tag. This helps to get the required appearance and creates a valid DOM tree, but makes some styled elements unreachable through the DOM

-

KHTML/Webkit acts pretty much the same way as Gecko

-

Opera closes both tags when the bold node is closed, but then opens a 'phantom' italic node until it reaches the italic closure. This creates a valid DOM tree and applies styles similarly to Firefox, but creates unnamed nodes

-

IE makes the tags overlap: italic is considered both a child and a sibling to bold. This makes any recursive operation on the DOM tree circle endlessly

Of all, Opera's is probably the closest to the 'proper' solution':

<b>bold text

<i>italicized and bold text</i>

</b><i> italicized text</i>

You could also do:

<b>bold text</b>

<b><i>italicized and bold text</i></b>

<i> italicized text</i>

for a more semantically correct display.

You could also use CSS for styling (the STYLE tag must be in the document's header). Remember, I'm using uppercase letters to name tags in my explanations, but writing them in lowercase in actual code. Writing them in lowercase is recommended in HTML 4 and CSS, and you must do so for XHTML:

<style type='text/css'>

.fat {font-weight:bold}

.bent {font-style:italic}

</style>

...

<span class='fat'>bold text </span>

<span class='fat bent'> italicized and bold text</span>

<span class='bent'> italicized text</span>

That's the cleanest implementation I know (notice that there are only 3 nodes, all on the same tree level, and that the second one uses multiple CSS classes). Instead of spans, you could also use EM and STRONG tags, allowing screen readers to change voice intonation for disabled users.

Obviously, properly nesting tags removes a lot of headaches–and explicitly closing all tags (as required by XHTML) helps to remove a great deal of confusion over tag scopes: there's no more need to remember what tags must be explicitly closed, as all of them must be.

Now, nobody is safe from making mistakes. Generating content (as when you use PHP, ASP, Perl, Python or Ruby to generate web pages) can make predicting a page's structure difficult. I won't deal with these languages here; I will just say that following the guidelines and advice herein may help you organize your generated documents better, and make the process clearer.

One very simple way to prevent problems is to ensure that as much content as possible is generated as complete nodes, for example by generating mark-up starting with an opened tag and ending with that same tag closed, or insert generated content inside a properly closed tag.

Then, while testing, XHTML on a modern browser will make errors stand out right away (provided said XHTML is sent with a proper MIME-type: application/xhtml+xml): browsers will ask for explicitly closed tags all the time; will require tags and parameters to be case sensitive; and will demand a correct DOM tree. Once a browser detects no more structural errors, you can send the code to a validator that will ensure compliance of the code with its header's signature.

In short, this will make sure that you're not using Frankenstein-ish HTML 3.2 code in an XHTML 1.0 Strict document. One of the best validators out there is the W3C's automatic validator: http://validator.w3.org.

A validator will also ensure that your document's encoding matches its header's encoding (great for testing that your server does respect your encoding instructions, which can be a pain if your content includes non-ASCII characters).

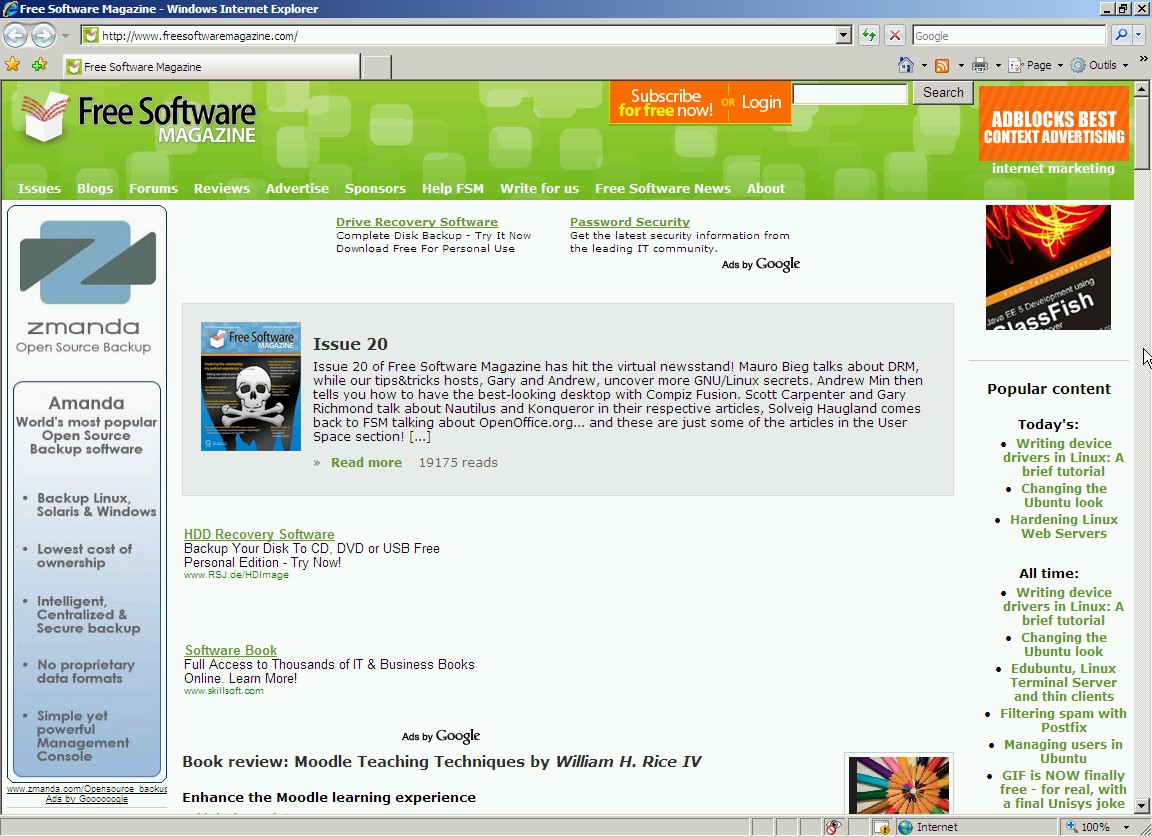

Validating your page has, at the very least, the advantage of ensuring the least discrepancy between browsers: if browsers don't deal with incorrect mark-up in the same way, they at least mostly agree on how to interpret correct code. Since XHTML 1.0 Strict has stronger syntax requirements than HTML, it leaves even less room for misinterpretation.

If browsers don't deal with incorrect mark-up in the same way, they at least mostly agree on how to interpret correct code

Structuring, why it throws you

I previously mentioned proper tag ordering: some tags can only contain some other tags, and some tags must have a specific parent before they can be used. The most obvious case is, for example, that a table row (TR) must be inside a table (TABLE); and a table cell (TD), inside a table row. Less well-known, the table header (THEAD) and table footer (TFOOT) must be located before the table body (TBODY).

In the same vein, a table must not be in a paragraph (P), and a division (DIV) can't be inside a list element (LI); a list element can only be found inside an ordered list (OL) or bullet list (UL). Validators will pick up on these, and also on missing attributes: most famously, an image (IMG) must include all of these to be considered valid:

srcor "source" (that seems obvious)heightandwidth(they allow document layout tracing before the image is loaded)altfor alternative parameters (for disabled users, text-only browsers, or broken source)

Harder to spot (but some validators, especially accessibility-oriented ones, will help), headings (H1, H2 etc.) must be properly ordered. This brings us to a point that seems like mere nitpicking, but is actually at the crux of today's problems.

Many web authors seem to have forgotten that HTML isn't a presentation language: it's a mark-up language, used to give sense to elements. But since H3 tags (for example) are usually displayed by browsers as written in a bigger font and as a block element (meaning, an element that is represented with a carriage return before and after its content), they sometimes use it to mark big text paragraphs instead of paragraphs containing styled SPAN or (semantically better) STRONG tags.

Similarly, using tables with 1px-wide images as spacers to center some content on a browser's window, is not what HTML is for–and not all browsers will deal with such tricks in the same way! Not to mention the overhead on download time! Since tables contain lots of mark-up and you need an external element (with an HTTP request) for this trick to work, it makes pages unnecessarily bloated and, even worse, unreadable to screen readers.

How should you do it, then?

If you want to change the appearance of a web page, first structure it correctly: use headings to mark heading levels—and chain them correctly! No H4 right after an H1, use tables to present tabular data, use lists for enumerations; and DIVs to divide data into significant blocks (content, menu, etc.), instead of table cells. You'll use CSS later on to position them.

Now, even though those Strict guidelines seem restrictive, many tags exist that allow you to structure your page very precisely, and at the same time make it easier and more clear to navigate: heading levels, address blocks, field sets, table heads and foots linked with table bodies and captions, column groups, option groups, and so on. Merely using these when appropriate will make your page easier to read–especially with a screen reader (like Orca), so accessibility benefits from this work (and, incidentally, some search engines enjoy well structured pages, and give them a slight bonus).

One thing that happens quite often, for example, is using tables to present forms: input on the right column, input label on the left column. What many web authors seem to forget, is that forms and inputs have a set of tags that work much better:

-

Group inputs with a

FIELDSET, which gets labelled with aLEGENDtag -

Dedicate a

LABELto an identifiedINPUT: this allows better selection, since a click on the label will select the input (useful with hard to hit check boxes) -

Use lists and sub-lists on those field sets, you can organize them in a tree fashion, making them more readable. Numbered lists also allow you to keep your hands off said numbering

-

With a few CSS tricks, you can also make certain that all inputs remain aligned

With a content generator, a well-structured page is essential. Since all elements are given a place and a level in a document's flow, changing any part of the page is reasonably dynamic: content will flow as ordered without any unpredictable behavior.

However, non-styled tags look a bit dry (think "word processor" dry), so you may want to style these so as to make your page look nicer–and that's the role of CSS.

Living in style

Content (or "Cascading") Style Sheets are the most-used means of giving style to your page, and date back to Netscape 3, while IE 4 and 5 were off to a very good start with them. Using them makes stuff like FONT tags or "border" parameters pretty much useless, and bases itself on an elegant method: in a correctly organized HTML document, the significance of an HTML element should be pretty much self-explanatory, so all you have to do is say "all paragraphs should be written in a bold, serif font with a 16-point font size" and that's it.

Still, you may require a bit more control than this.

Paint a target

CSS is based on classes and identifiers. The more precisely you refer to an object, the more likely it will get a style applied. CSS is case sensitive: steer clear of uppercase letters for minimum trouble (even though IE up to 7 doesn't respect case sensitivity at all).

'Generic' classes are simply the tag's name. For example,

p {font-weight:bold}

will write all paragraphs in bold, wherever they are on the document. However,

div p {font-weight:bold}

will only style paragraphs located somewhere in a DIV. Even better,

div > p {font-weight:bold}

will only write paragraphs which are direct children of DIVs in bold. '>' is called a "selector" here.

But, what happens if you want to style both paragraphs and list elements (LI) the same way?

p, li {font-weight:bold}

will do that for you. If (even better) you want to style only some of these, you could also create classes (as we've seen before):

p.fat, li.fat {font-weight:bold}

which will apply only to those P and LI tags that have a class='fat' parameter defined. A shorter way to write this previous rule would be:

.fat {font-weight:bold}

Finally, if you have given a unique identity to an element on your page (say, a <DIV id='menu'>), you could also target it directly with:

#menu {font-weight:bold}

Or, if you want to ensure that only DIVs identified as 'menu' get the style, you can use:

div#menu {font-weight:bold}

Which can be useful if your pages' structures are different, and you want to keep the same style sheet across all your pages.

Now, these are merely examples of how to style text, but CSS allows you to deal with element padding, borders, colors, decoration, font spacing, margins and positioning, document flow, layer positioning, layer depth, display media, backgrounds, generated content, and even some basic events.

If you have two conflicting rules (for example, two rules defining a paragraph's border), the priority is defined like this:

-

The best-identified description gets precedence (p.fat has precedence over .fat)

-

On identical identification, the rule written last in the style sheet has precedence (you may get a warning on CSS validators that a property has been redefined)

-

Depending on browser,

!importantafter the rule overcomes the preceding rules

CSS does have some strict rules, coming right from how HTML elements are defined: for example, an in-line element should not contain a block element, a proportional size is always calculated versus its parents' dimensions, you shouldn't have the same color for font and for background. It also has a strict syntax–so, you should validate it too.

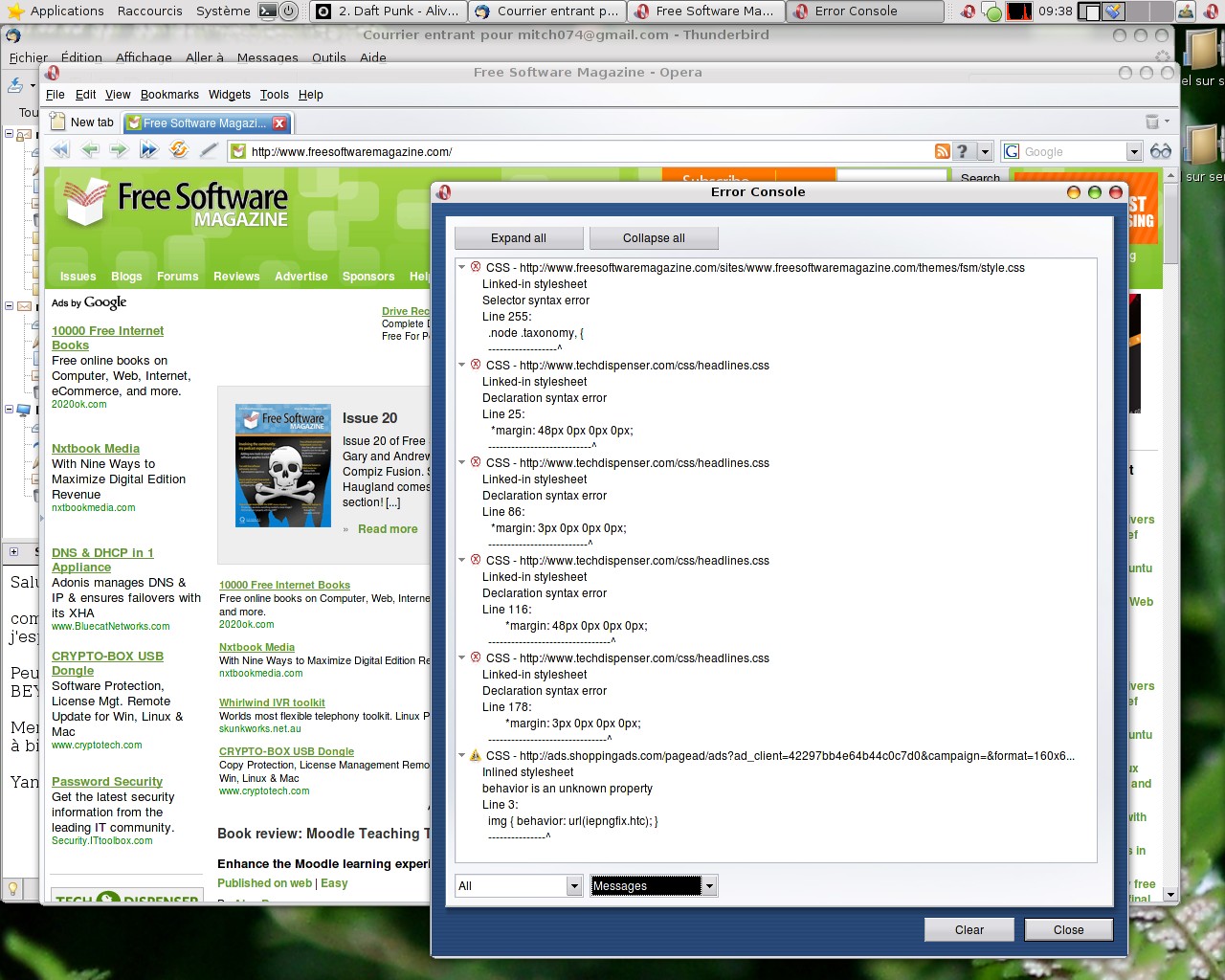

But syntax and design isn't CSS' biggest problem: while most modern browsers handle basic CSS (also known as CSS 1) very well, they all present unique behaviors; may not support a property or all of its options; or may deal with some lack of precision in later CSS specifications (currently 2.0 and 2.1) in a way that doesn't agree with another browser's behavior.

Misfires!

Of all currently supported browsers, Mozilla's Gecko engine is fairly well regarded (version 1.9, coming with Firefox 3, improves CSS support in many ways and makes it on par with Presto), Opera's Presto is pretty much a reference implementation (although not quite perfect), KHTML/Webkit is very good, W3C's Amaya can at least understand advanced CSS without getting too distracted, and as you guessed, IE chokes (though version 7 does a bit better and version 8 may just work—let's hope it gets better after its first beta!).

IE can be made to behave with some proprietary syntax and layering bugs one on top of the other:

-

IE 5/Win32 has a faulty box model: it doesn't handle block and in-line elements correctly; it deals with overflow in a non compliant manner; and it uses incorrect dimensions when dealing with element width and height. You can however use conditional comments and parsing errors to pass it settings other browsers won't see. Quite often, it's a matter of using one bug to correct another

-

IE 5/Mac OS was very good at the time, but it has been discontinued

-

IE 6 supports some 'Strict' CSS parsing that solves the box-sizing problem. Yet, most problems found in version 5 remained unfixed, meaning you can still stack bugs to obtain the desired results

-

IE 7 deals with the most obvious IE 5/6 bugs and limitations, and adds support for some selectors, along with some unique bugs, and retains the infamous

hasLayoutproperty that makes HTML objects behave differently from one second to the next -

IE 8 should be a great improvement, though. It currently passes the Acid2 test and supposedly gets rid of

hasLayout. My own tests done on Beta 1 were far from conclusive though: with a design I'm working on it shows no real support for pseudo-elements, and introduces a bunch of weird positioning bugs

I won't make a more complete list of those bugs: ( http://www.positioniseverything.net is a great resource, and Dean Edward's IE7 script makes IE 5/6 almost standards-compliant). Even Microsoft has recognized that its Trident engine sucks eggs when parsing CSS 2.

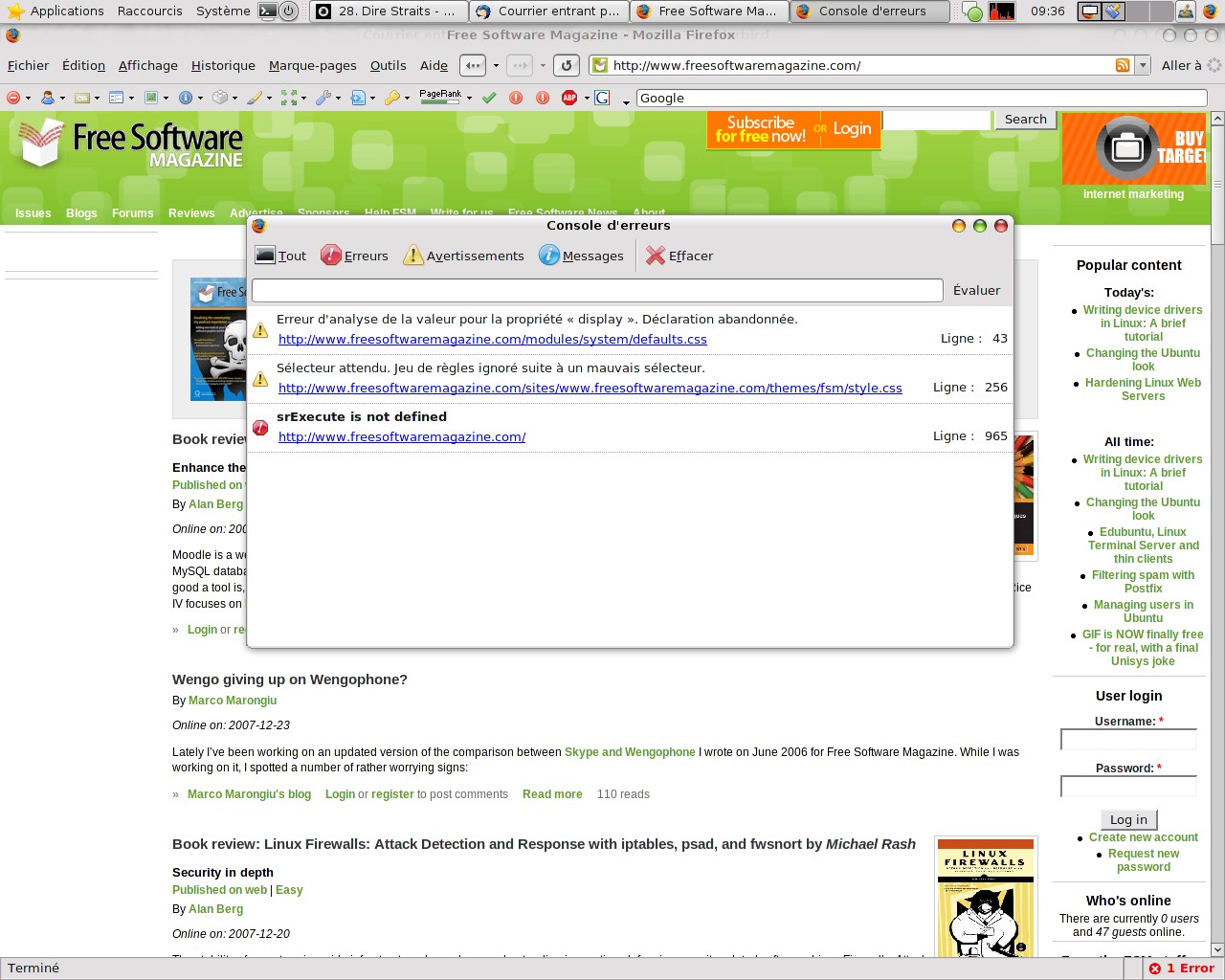

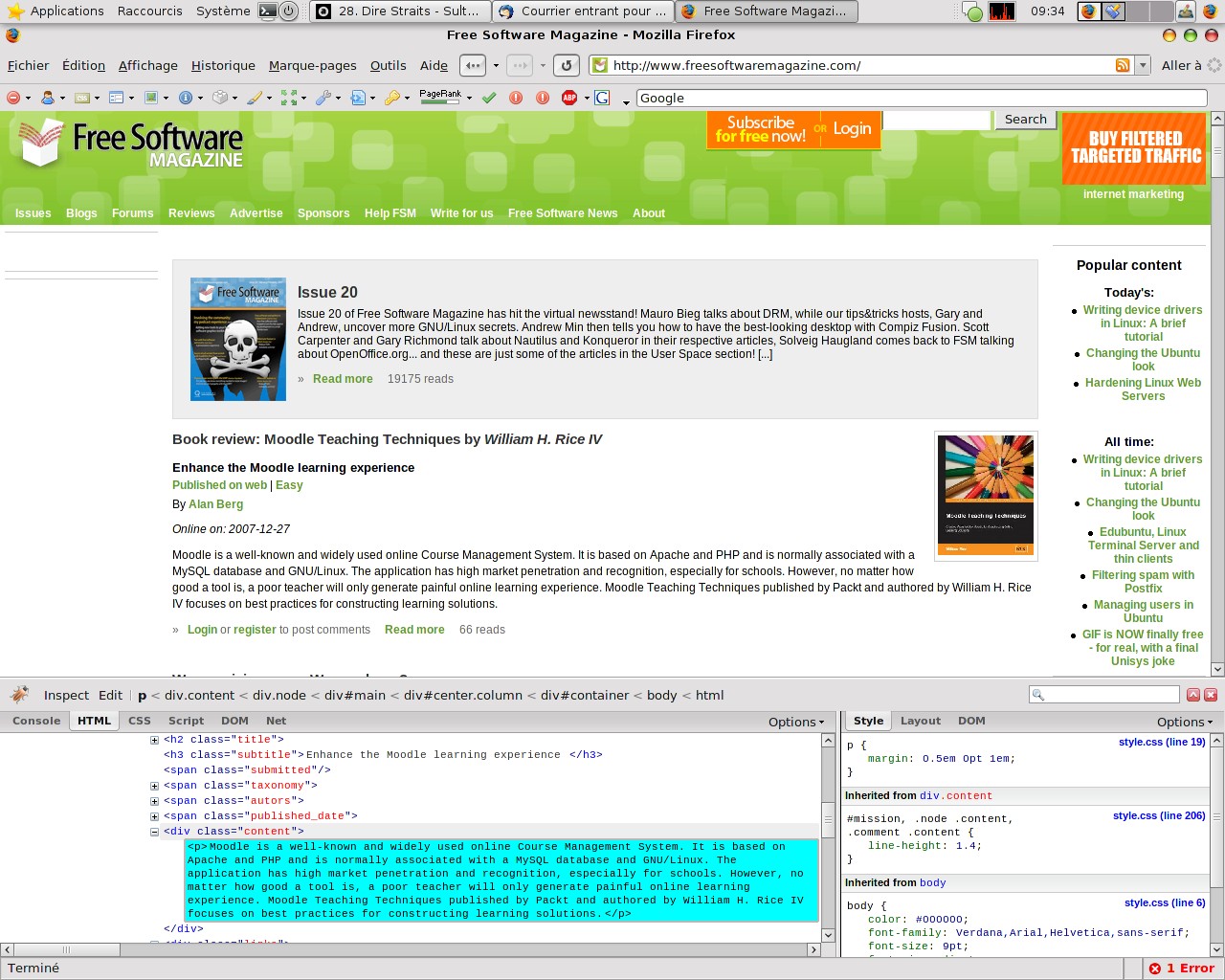

Validate objective

Firefox's developer toolbar contains a CSS debugger, but the most complete CSS validator out there is the W3C's CSS validator: http://jigsaw.w3.org/css-validator will not only tell you if your code is valid, but also give you notices on where it is correct but may be troublesome. If sent along with the document to which it should apply, this validator can also tell you what otherwise correct rules are not valid in the document's context. In this case though, you should load the page twice: sometimes the validator misfires on some elements on first load, but will then read them correctly on the second.

Using external style sheets is an excellent way to ensure that your whole web site has a consistent appearance. Allied with similarly-structured HTML documents, it makes maintaining a complex website with many pages quite easy, even with only a text editor, and reduces overall download times by reducing page sizes. Indeed, external CSS files are often well-cached by browsers. Thus integrating style in the page's content isn't always the best solution.

Some browsers are also able to apply different style sheets depending on media, making 'printer-ready' or 'hand-held ready' versions of your pages redundant (this is done through the media parameter of the STYLE tag. For example, specifying media='screen' will make the printed page look very dry in Firefox and Opera). You can also create alternative CSS files, and allow ultimate customization for your user (a 'large size' file for near-sighted people, an elevated contrast one, or just different looks).

CSS can also be used to present users with simple behaviors: small pop ups, hover effects, roll-over menus, pseudo-frames, and so on can be made with some CSS and absolutely no "active" code–making your website quite safe and perfectly usable with a browser that has JavaScript disabled (and many people, in these days of Trojans and worms, do disable JavaScript).

Still, if you want to give more user interaction on your web pages, you'll need to start scripting.

JavaScript, Jscript, and ECMAscript

When I mention web pages scripting, I do mean client-side interaction programming. While a lot of scripting happens server-side and actually represents the most basic way to create web sites that allow interaction, client-side scripting is stuff that is run directly in the browser: opening a new window, automatically correcting a form field's content, starting complex behaviors depending on user actions or on server events (think AJAX), showing or hiding page elements depending on mouse or keyboard events, or providing some page animation. All of this requires some form of client-side programming.

Historically, client-side programming has been done through two methods: integrated applets running in virtual machines which manipulate the document's content or direct manipulation of the page's content by the browser itself, through the use of a script.

The former method is the category into which Java applets, ActiveX controls, and Flash objects fall. They are powerful in their own ways, but require virtual machines. Since not everybody has Java or Flash installed, they are not reliable for a broad audience. ActiveX controls are IE/Win32 only.

The latter method is basically the realm of ECMAscript, also known as JavaScript (all W3C-friendly browsers use this name) or Jscript/Active Scripting (IE). Luckily, VBscript was put to death some time ago.

The HTML document is your base of operation: while it is perfectly possible to create page elements purely through scripting, it is often tedious, performance-killing, and much heavier than creating a complete (and correct) HTML document that you will then modify through scripting. The same thing applies to styling: creating different classes for the different appearances an element may take and using scripting to switch an element's class is faster, lighter, and simpler than rewriting an element's style through scripting.

Here is an example:

var paragraph = document.getElementById('test');

paragraph.onmouseover = function(){

paragraph.style.font-size = '12px';

paragraph.style.font-weight = 'bold';

paragraph.style.color = 'red'; }

paragraph.onmouseout = function(){

paragraph.style.font-size = '8px';

paragraph.style.font-weight = 'normal';

paragraph.style.color = 'black'; }

This would make a paragraph identified as test become red, bigger, and bolder when the mouse cursor hovers over it, and return to the original black, slim, and small appearance when the mouse cursor leaves it.

Although it would be perfectly valid to look up test every time you use it (with document.getElementById('test')), it would be very wasteful—just as if you were to close a book after each page you've read and look for the next page by counting from the beginning of the book.

Even without the redundant lookup (herein avoided through the use of the paragraph variable), though, you'd still get a rather large CPU spike, and (on slower machines) some display lag caused by several direct DOM manipulations.

Or, you could create two CSS classes:

.bigred {font: 12px bold; color: red}

.normal {font: 8px normal; color: black}

and have these lines of script to switch them:

var paragraph = document.getElementById('test');

paragraph.onmouseover = function(){paragraph.className = 'bigred';}

paragraph.onmouseout = function(){this.className = 'normal';}

This would behave identically to the first example, but use radically less CPU time (around 75% less!) and take effect without delay. Also, in case the user has disabled the use of CSS, you don't need to disable the JavaScript part to prevent strange happenings: it will merely switch a class that does nothing to a class that also does nothing.

You may notice that I used the this keyword for the second option; I could have used it for the first too, and saved a few bytes.

Note that, for this particular example, no JavaScript is actually needed, as CSS knows a few events like hover, select and visited. Indeed, you could declare your CSS like this:

#test {font: 8px normal; color: black}

#test:hover {font: 12px bold; color: red}

However, this approach wouldn't work with IE 6 or lower without the use of some glue if #test isn't a link with an href parameter. You may want to, for example, add or remove some text from #test or use a different event, which CSS doesn't cover.

This works in most situations, and even in the rare case where you want to specify your CSS through JavaScript (because said style is dynamically generated, for example), the first situation is still valid when you modify only one style property. However, if you have to set up two or more, another method is preferred:

paragraph.onmouseover = function(){

paragraph.setAttribute('style','

font: 12px bold;

color: red');}

paragraph.onmouseout = function(){

paragraph.setAttribute('style','

font: 8px normal;

color: black');}

This is the W3C-friendly method. While IE doesn't throw an error, it doesn't apply styles when set this way. However, a proprietary property (which doesn't disturb other browsers) is object.style.cssText (this is, if you want, the CSS equivalent of innerHTML). As you may guess, it works the same way:

paragraph.onmouseover = function(){

paragraph.style.cssText='

font: 12px bold;

color: red';}

paragraph.onmouseout = function(){

paragraph.style.cssText='

font: 8px normal;

color: black';}

With these methods you can thus specify inline-level CSS styles with a single DOM operation, achieving the same effect as lengthy direct DOM modifications.

To recap on HTML and CSS correct use and validity: if your HTML is correct, you will have less trouble with different Document Object Model interpretations from one browser to another (IE's unique ability to graft DOM tree branches back onto badly nested tags has created enough endless loops as it is). If you have already created classes and styled them well in CSS, changing the appearance of a page element will require a single line of script code instead of a long, complex, risky, and CPU-intensive DOM manipulation.

An eventful document

For those of you already familiar with JavaScript, you must have noticed that I used the legacy Netscape event model in the previous example. It is the best supported of all, with the lowest overhead, and is really easy to use for simple actions. Basically, you take an object and (after the '.') add on plus the name of an event to it, and associate a function to this method. Easy, fast, simple. It is, however, a bit limited:

- you can't associate several functions to the object unless you group them inside another function

- you can't manage these multiple functions dynamically

- you can only use predefined event listeners

- and even when you use the grouping trick, functions will only start sequentially

More advanced event management, like dynamically associating several actions to the same event listener and firing them all simultaneously, can be done in two ways:

-

W3C's event model: it expands upon both Netscape's and IE's models and uses the addEventListener method to add one or several actions to different events happening to an object. It detects events on both capturing and bubbling phases

-

Microsoft's event model: it relies on a proprietary property to the window object, called window.event, to capture events happening to the page. Its structure is similar to the W3C's method (which was created before), but it detects events on the window's level, not the targeted object's, making it effective only on bubbling phases (very annoying when you want to keep an event active on an element that contains other elements, or for detecting the event's origin).

What's "bubbling" and "capturing"? Simply put, when your mouse hovers over an element, it also hovers over its parent.

Capturing means that the browser takes the event through all children's ancestors up to the window level (if an element handles the event, it can "capture" the event and prevent it from going higher up the DOM).

Bubbling happens when an event starts from an object (either from having gotten up to the window object in capturing phase) and goes down through all its children. For a very complete explanation, look at http://www.quirksmode.org/js/events_order.html and http://www.quirksmode.org/js/events_advanced.html.

Opera supports both models, as does KHTML/Webkit. Gecko supports only W3C's, and IE supports only its own.

The biggest problem with IE's method is when you want the event to trigger a function to be run on the object (such as making a button blink when the mouse hovers over it). Let's look at some pseudo code:

ON myButton WHEN mouseover DO paintItRed

where myButton is the object, mouseover is the event, paintItRed the function. Some CSS first:

isRed {color: #F00} /* don't you love those shortened hexadecimal color values? */

The legacy model would put it this way:

function paintItRed(){this.className = 'red'; }

myButton.onmouseover = paintItRed;

The W3C model would put it this way (previous function remains identical):

myButton.addEventListener('mouseover', paintItRed, false);

And IE would need it to be written this way (and also the function will need to be changed):

function paintItRedIE(){window.event.target.className = 'red'; }

myButton.attachEvent('onmouseover', paintItRedIE);

This is a simple example. For bigger functions, having to duplicate them all is a Bad Idea (TM). In practice, people wanting to use the advanced methods create a 'wrapper' function that detects the model in use, switches to a code path depending on the situation, and passes the target object as a parameter to the function. They then call the wrapper function on the object every time they want to attach an event listener to it.

However, using this method makes removing event handlers tricky.

Scripts and variants

JavaScript was first created as a cooperation between Netscape and Sun, to make a browser interact better with a Java applet. It then took on a life of its own. Very soon, several browser vendors started creating half-compatible versions of JavaScript, and in an effort to unify these, the ECMAscript norm was created–with version 3 finalized in 1999.

Version 4 is still being reviewed. With IE having frozen the browser landscape for five years when Netscape went belly up, there was less incentive to keep improving it. Now however, AJAX is pushing the limits of ECMAscript 3, and older engines have started to have trouble with it:

-

Mozilla's JavaScript engine used to leak memory a lot. Things have gotten much better with later revisions though, and its DOM engine is the most compliant of all. It has the best JavaScript debuggers out there, and it's fast, but it doesn't implement many of IE's proprietary elements

-

Adobe currently uses two Javascript Virtual Machines (JSVM): KDE's Kscript (in Safari) and ActionScript (in Flash). The latter is now in Mozilla's custody, so we'll see consolidation in free JavaScript engines

-

Opera's version is (arguably) a bit slower than Mozilla's, and slightly less stable. It adds most of IE's proprietary DOM elements (like its event model) on top of the W3C's

-

IE's Jscript engine is mismatched with the browser's DOM engine, creating orphaned nodes all over the place. It's also unstable and limited: its garbage collector requires supervision bordering on hand-holding, prevents direct memory management, and leaks (see Drip and sIEve)

That's why passing off as much work as possible to correct HTML and CSS can help: it means less JavaScript to type–and less Jscript "glue" to nanny IE.

Performance-wise, the less you directly manipulate the DOM, and instead use existing HTML and CSS constructs, the faster your web application will get. Joseph Smarr of Plaxo, Inc. does a very good demonstration in his OSCON 2007 presentation. Manipulating the DOM is so expensive, in fact, that it is recommended to cache as many DOM manipulations as you can and apply them only when they really are needed: for example, instead of:

document.write('<p>adding a paragraph!</p>');

document.write('<p>adding another paragraph!</p>');

document.write('<p>adding a last paragraph!</p>');

you'd be better off using:

var domAddition = '<p>adding a paragraph!</p>';

domAddition+='<p>adding another paragraph!</p>';

domAddition+='<p>adding a last paragraph!</p>';

document.write(domAddition);

This is all well and good for making your JavaScript work, but is it enough to make it run well?

Tighten your scripts!

Here comes trouble: while HTML is a mark-up language, and CSS is a styling language, web scripting falls into the category of programming languages–with typing trouble, variable vindication, and memory madness.

Now, you should simply forget about using IE to debug your script: its debugger is barely able to find out DOM errors and is simply unable to raise programming problems. Moreover, it is awkward to use, and its interface is a Windows 95 reject.

Mozilla Firefox is more solid here: the "Web Developer" tool bar gives an easy access to the JavaScript console (which has helpful error and warning messages), and debuggers like Venkman or Firebug make it easy to find programming errors and analyze a complete document. They are able to monitor variables and objects, and use breakpoints.

Opera also comes with valuable debugging tools, but their interface is not as intuitive ("your mileage may vary") and add-ons are still considered Alpha quality.

None of these can help you with wrong programming or dumb mistakes (like creating a global variable due to mistyping).

I like fast–fast is good

Depending on how and where you call objects, you can slow down a script to a crawl!

JavaScript is an interpreted language. As such, any mistake or badly-thought-out construct can have dire performance implications: depending on how and where you call objects, you can slow down a script to a crawl! And on the other hand, a single line of code, strategically placed, can make your code run many times faster. In all, several guidelines often come forward:

-

Defining the complete path to an object finds it much faster than merely looking it up by name. For example, calling “input1” is much slower than calling

document.forms.nameOfForm.input1 -

Assigning a variable to an often-used object or property removes the need to look it up

-

Local variables are looked up before global ones are. Within functions, declaring your variables as local boosts the function's execution time (on top of preventing memory leaks)

-

Comparison with zero is faster than comparing with any other number, a nice boost can thus come from using reverse counters

-

Comments are evaluated too, so don't put comments in areas that are often parsed, like loops

For example, if you have a form named myform and want to go through all of its inputs, logically this is what you'd do:

for ( i = 0; i < myform.elements.length; i = i+1){

miscellaneousStuff = 15;

myform.elements[i].value = miscellaneousStuff/i; //do some stuff to an element

myform.elements[i].property = other_stuff;

}

Here, you have one useless global: miscellaneousStuff. Its value won't be freed once the loop is over. Even worse, it will be reset on every loop. Moreover, you ask the browser to look up your form's elements length on every iteration of the loop. And finally, you ask the browser to parse your comment on each and every loop.

You'd get a faster loop by doing this instead:

var miscellaneousStuff = 15;

var currentInputSet = document. myform.elements;

for(var i = currentInputSet.length-1; i >= 0; i-- ){

var currInput = currentInputSet.i;

currInput.value = miscellaneousStuff/i;

currInput.property = other_stuff;

}

// do some stuff to all elements inside myform

First, the counter: we only look up the length of the form's elements array once. Then, we compare with zero (which is faster than comparing with any other integer). Finally, we don't have to refer to i, then operate on i, then change i; instead, we directly change i. Please note, however, that you have to shift i's value range one rank back if you intend to use it inside the loop: the initial construct started with i=0 and ended at i=max value, not performing the action for the latter. Thus you have to start one step lower (i=max-1), then allow the action to proceed one step further (i >=0).

About the comment, an even better location would be inside a PHP, Perl or ASP comment: that way, it wouldn't even be downloaded by the client; for example: <?php /* add comment here */ ?>.

Of course, this is possible only if your JavaScript is generated rather than a static file.

I kept the external variable (because it might be used later on). By caching the form data in currentInputSet, we avoid having to look up every form and then all its elements. Also, we directly access the object we want to use instead of going through all of its parents.

To make it even better, you could access it all at once, and group all properties and methods assigned to the object in one go:

currInput = {value: miscellaneousStuff/i, property: other_stuff } ;

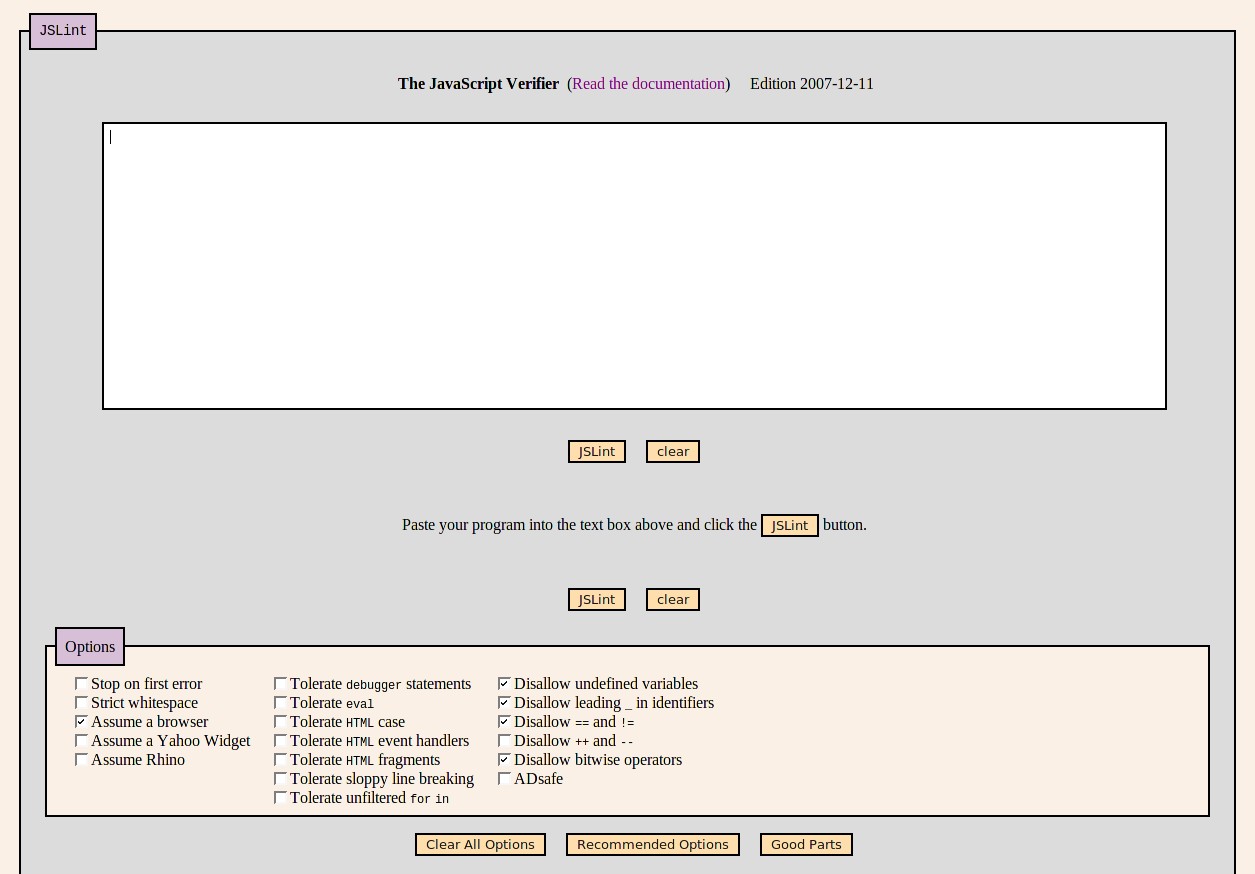

but the current solution is generic enough to be readable. Now, it would be nice to find a way to evaluate all those objects, just to be sure that said unruly globals don't hang around unattended. And here comes "JSLint".

Clean up after use

JSLint is a JavaScript-based JavaScript validator: it will read JavaScript code you submit to it and raise warnings or errors on constructs that are not in themselves incorrect, but which can lead to unpredictable behavior:

- incorrect use of carriage returns, spaces, and commas

- potential type mismatches and false positives or false negatives

- awkward or non-optimal syntax

- globals invasion

- dangerous reliance on default settings

How those may impact your scripts isn't apparent at first, so let's look deeper.

Incorrect use of carriage returns: JavaScript allows you to end a statement with a comma or a carriage return. However, the carriage return can sometimes be considered a space. Only the comma unequivocally delimits statements: JSLint tells you where you should put these.

JavaScript is a typed language that performs automatic type conversions as often as it can; sometimes though, this automatic conversion may fail

JavaScript is a typed language that performs automatic type conversions as often as it can. Sometimes though, this automatic conversion may fail.

Incorrect use of comparison operators

-

'=' means that you associate an element with another, or with a value

-

'==' means that you compare any two elements' values

-

'===' means that you evaluate two same-typed elements' values

Obviously, the last will return false whenever the two compared elements are of a different type. While 1 == '1' is true, 1 == 'two' is too (the first is a number, while the second is a non-null character string, automatically converted to 'true' which is worth 1). The expression 1 === 'one' would fail, and so would 1 === '1', but 1 === 1 would be true.

Because of the previous point, you will have to explicitly convert types; parseInt and parseFloat would then be used quite often, allowing you to do stuff like 1 === parseInt('1') with success.

It's good, because it helps prevent any goofy result you'd get when comparing variables and inputs in a domain you don't always control. It's also bad, because it requires some extra code, yet your code would be much more robust. But then, JSLint would complain that you didn't include the radix. Huh?

Simply put, numbers can be represented differently on a computer: you have "human" base ten (0 to 9), but also hexadecimal (0 to F) and binary (0 to 1).

Now, what happens when you do parseInt('015')? It will consider the leading 0 as an indication that you're going hexadecimal, and instead of a base-10 value "15", you'd get a base-16 value worth "15", which, in base-10 is 21.

The radix is the optional parameter for parseInt that gives it its basis: correct use of parseInt would thus be parseInt('015',10) which would be 15. One thing you can do, is create a small function that takes care of the radix: say,

function getDec(val){return parseInt(val,10);}

and use this instead of parseInt. Now, not everything is perfect, and you will get a performance impact. I iterated all three solutions 30,000 times on a string starting with a non-zero digit, marking start and stop time on all four browsers, then ran them a dozen times and noted average results:

- with no radix, Firefox takes the lead; Opera and Konqueror are 10% slower. IE 7 trails a further 20% behind

- specifying the radix makes Firefox "as slow as" Opera and Konqueror. IE 7 stays slow

- Using the wraparound function adds a 40-50% overhead to Firefox and Opera, and more than doubles the execution time on IE and Konqueror.

Overall, just specifying the radix has the least impact for the safest approach; use the function only if you are very space-constrained.

Regular expressions

JSLint can check regular expressions (RegExp) and prompt you for non-escaped characters. While it can't second-guess you, it can detect when special characters are in a context where they must be used literally, thus they should be escaped.

Some more tips can be given by JSLint, such as not using Perl/PHP-like collection['identifier'] syntax, but collection.identifier instead (Gecko's debugger also hints that it converts the former into the latter on execute, you may want to save it the trouble). This is not absolutely required, but this particular example shows how one can complicate one's life and code for nothing.

Globals

Finally, JSLint will count all global objects used in your script. Using an object before it is declared is bad, as it requires the whole script to be parsed before being interpreted. Declaring a function before using it has it interpreted first, then called and executed (instead of having it called and then interpreted and executed): interpreting adds some lag that can be noticed by the user.

What is absolutely frowned upon though, is using a variable without declaring it first: you need to create it with the var keyword, and then use it. The location of the var keyword defines its scope.

Unfortunately, not using var will make the variable completely global. In a main loop, it's not too much of a problem, but calling it inside a function will make it keep its value across runs of the function. If the variable were a counter, things could go very bad, very fast.

In terms of performance, globals are not good either: most garbage collectors have trouble dealing with them. Abusing globals may thus create memory leaks all over the place.

For that matter, although the consequences are less dire, using a function before declaring it is bad: JSLint will report it, and the solution is very simple: make it a habit to put all your global variables at the top of your JavaScript, then declare all your functions, then start your main program loop.

You know, like when you program Pascal or C.

Personally, I found that the harrowing work of tightening my code yielded good results

It is very discouraging to read "too many errors–parsing stopped at 4%" the first time you feed JSLint your otherwise perfectly running code. Personally though, I found that the harrowing work of tightening my code yielded good results:

- it made me spot potential and real bugs

- it helped me make it more simple and slightly boosted its execution speed

- increased stability prompted me into adding a few features I didn't feel confident about adding before

- tighter type checks helped me remove some other clumsy manual checks I had to do

On something as slow as interpreted code, code clean-up really helps. If you're worried about your code size, just tell yourself that an extra 10% line length may save you some full lines later on, won't alter code compressibility (for gzip encoding) and will give your code up to a 50% boost on execution. Moreover, since the most basic syntax is the one most browsers agree upon, keeping it simple will strongly reduce the time you'll spend debugging this or that browser.

Conclusion

Making your web code extremely strict and tight is not a waste of time. On the contrary, making it high-grade will allow you to cut debugging time to a minimum and reduce testing and compatibility-gluing a great deal. It will also provide basic optimizations and reduce the need for redundant checks.

Moreover, maintaining this code becomes a real pleasure: adding a new page, revamping menus, improving appearance, or adding functionalities becomes so easy (provided you stick to those resolutions) that you won't hesitate any more to add stuff just for the fun of seeing it work perfectly on the first (OK, maybe second) try.

Bibliography

http://www.quirksmode.org/js/events_advanced.html is a complete overview of event models.

http://www.positioniseverything.net describes advanced CSS techniques, and several hacks and techniques one can use to make IE 5/6 behave.

http://blogs.msdn.com/ie/archive/2007/12/19/internet-explorer-8-and-acid2-a-milestone.aspx report on an internal build passing the Acid2 test.

http://home.earthlink.net/~kendrasg/info/js_opt provides some more advanced programming tricks geared towards improving JavaScript performance.

http://www.miislita.com/searchito/javascript-optimization.html contains several other, much more common, performance tricks.