Back in the good old days, when men were men, women were women and the standard way for two computers to talk to each other was through a cable plugged into the serial port, was when I first took the plunge into this “internet” thingy and signed up with an ISP. Then, armed with a modem, a telephone line that doubled as a fax, Netscape 1.1 and a sense of adventure, I surfed web sites, emailed the few others I knew who had also taken the plunge and joined in on worldwide discussions on what we called “News Groups”. I felt at the time I was at the sharp end of technology, that I had arrived at the next millennium early (this was still the nineties) and I had boldly gone into this brave new world of global communications where few had gone before. In a way, I had, when you consider what others around me in the UK were doing at that time.

First virtual experience

Soon after I had joined, my ISP decided to give all of its customers the ability to publish web pages for personal or business use. To announce it they came up with this excellent slogan—“Don’t just surf, make waves!”. They didn’t give us all our own server, of course, but some space on one of their servers they had implemented for the purpose. A staggering 512 kilobytes! An entire half meg! Not only that but they gave us use of a few CGI scripts to enable functionality like the emailing of results from forms that I could write and publish on my website. Wow!

My ISP encouraged us to create web pages with the slogan “Don’t just surf—make waves!”

This was, I suppose, my first experience of virtualization, although I didn’t think of it as such at the time. We (at first) did not have our own domain names, none the less the concept was born: that a large number of people could use an area of a single machine totally independent of others and could treat that area as their own, especially as far as anyone visiting is concerned. In short, the distinction between network and server had been blurred; someone could visit my site and, unless they looked at the URL at the top of the browser, would be unaware that I was sharing the hardware with possibly hundreds of others.

Technical advancements increased and soon the company I helped to run obtained a virtual host, similar to, as we think, one of today. It consisted of our own domain name, shell access to our area of the machine and giving me the ability to create my own web scripts, and perform email forwarding, mailing list management. It also came with all of the other paraphernalia we have come to expect from virtual host suppliers. This suited us perfectly because, for a relatively small financial outlay, we could produce a web site that, as far as most of the world’s population was concerned, was on par with the multi-million dollar sites of the corporations.

Virtual comparisons and progress

As the company grew so did our web requirements, and soon we needed a dedicated machine. We couldn’t justify the cost of getting a fast link to our offices—which were temporary in any case—so we co-located it with a host provider who specialised in that. We finally had “root” administrator access on our own machine and could install whatever software we considered necessary to run our business, without the limitations a virtual host restricted us to. Freedom to do what we wanted to at last! This, however, cost us considerably more money than the shared hosting that we had before.

Recently a significant technical advance has occurred with web servers on the market: onto the scene has come virtual machines. I currently use one of these as my personal web site. In effect a hosting company can give you the functionality of a co-located machine for the price of a virtual host. I have root administrator access to my machine and the facility to reboot it whenever I require. I can even connect to a special server using SSH and have access to the console of my machine, should I mess up the firewall configuration, which I found useful when I put the default firewall policy as “deny” and flushed the rules (oops!). I can install any software I like and even set up virtual hosts on it. I could even, if I wanted, choose which Linux distribution and kernel to use. All of this even though I share this machine with about fifty other people, all of whom are enjoying the same functionality for their own virtual machine, and none of us has access to each other’s machines at all. The distinction between “network” and “machine” is becoming more and more obfuscated. The implications to the small web server writer are enormous. They now have the facility to install whatever databases they like, and provide whatever services they like for the monthly price of a dinner at a mediocre restaurant. An equaliser between the corporations and the one-man bands indeed.

Free software has had an important role to play in this. In fact, more than just important. If the free software model didn’t exist, I can say with near certainty that virtual machines would not exist in the way they do today. Most virtual machines currently only exist in the free software world, on Linux especially. I believe that this is one area where Microsoft cannot claim that they out-perform Linux no matter what “independent” reports they commission for the simple reason that they have yet to produce a viable virtual web-server machine.

If the free software model didn’t exist, I can say with near certainty that virtual machines would not exist in the way we know them today

The way virtualization has advanced is very much on par with the ethos of free software. It is, after all, a tweak and an enhancement of the kernel and operating system. In order to successfully create a virtual machine program you need access to the magical inner workings of the machine and all of associated documentation. For proprietary systems this is often the exclusive knowledge, and always under the control of, the software vendor, and thus there exists an immediate obstacle to the development of such products—and “Why?”. The answer to “Why Not” is obvious. It creates support issues. It could well lead to the sale of fewer licenses, not more, it can create performance issues, and so on. Also, in the proprietary world, one of the major benefits of virtualization disappears. It’s difficult to see how a vendor would permit two instances of the operating system to be sold for any less on a virtual machine than on a real one. With this and the extra licensing they’d charge for the virtualizing software itself, a web hoster may well have to pay as much, or more, to provide a virtual machine as it would to provide a real one.

The free software version doesn’t have these handicaps. This means that when someone needed or simply wanted to write virtualizing software, all of the tools and information were at hand. This means that projects like User-Mode Linux could get off the ground, and be implemented and enjoyed without anyone’s licensing terms being violated, and the only people being harmed are the proprietary operating systems in the market, whose vendors have seen their share of it being reduced slightly more.

Virtualization types and advancements

As often is the case, the free software model doesn’t stop there. Virtualization is about to go to the next level. In the world of virtualization, a new kid has arrived on the block that is getting noticed. And the name of the kid? Xen. To understand why it is so significant we need to examine the different types of virtualizing programs. The names I have given to these categories are my own.

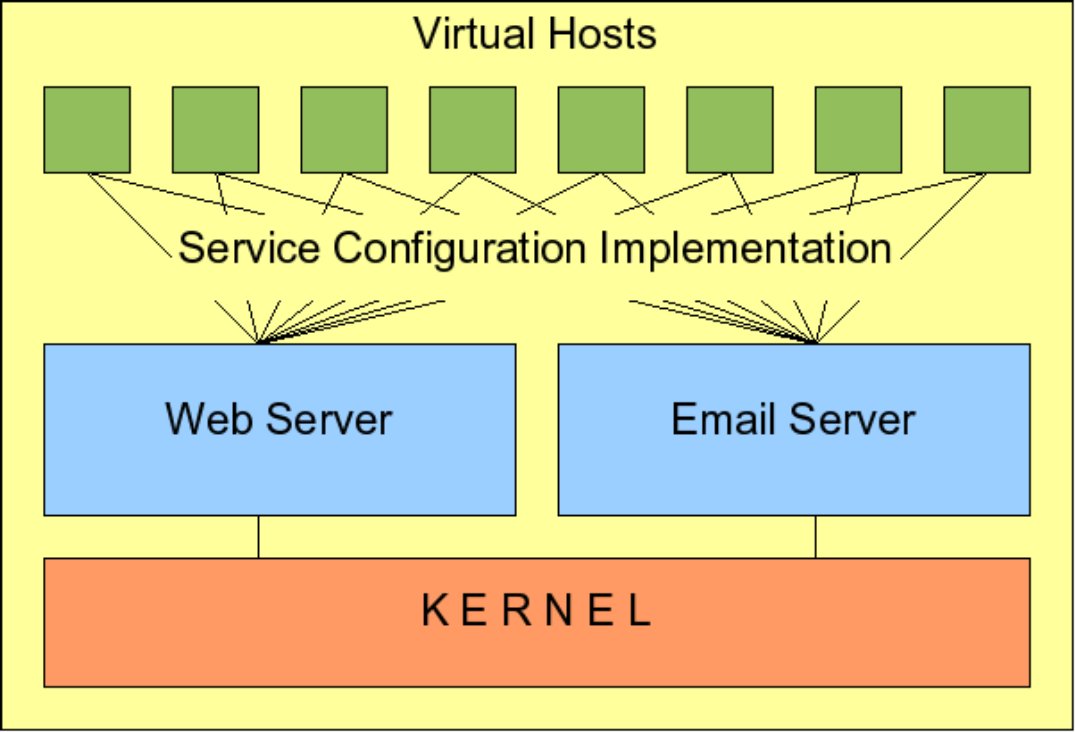

1. Virtual hosts

This is not really a virtual system, just a refinement of service configurations. The web and email services are configured so that more than one domain can be hosted, though each of the virtual areas of the machine are independent of each other, they all share the same kernel. Web modules, database engines and the programs installed are decided by the administrator of the main machine (also known as the “monitor” in virtualization parlance). Also, it’s often the case that all the virtual machines share the same IP address. This is the type of virtualization that most web hosting companies currently supply. The advantage of this is that it is relatively cheap and easy to set up—you can even do this on Microsoft’s Servers—also there’s no resource or performance hit from the virtualization itself, mainly because there isn’t really any. The disadvantage of this is that, although you have the cost savings of virtualization, the virtual machine owners do not have the benefits of their own machine. You cannot control what software goes on it. You do not have administrator or root access at all, so you can’t even change the time. Often, for these machines, you don’t even have command-line shell access. You are, to all intents and purposes, totally at the mercy of the web hosting company.

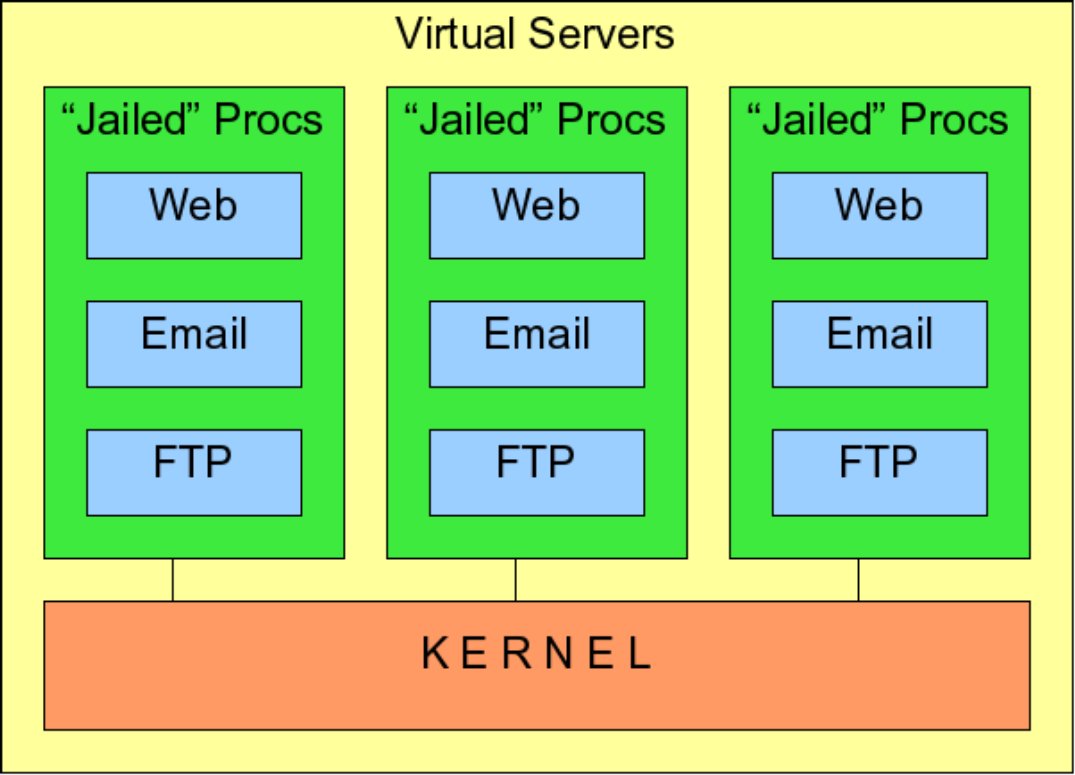

2. Virtual servers

Although the mechanics of this are similar to the “Virtual Host”, described above, it offers a far greater level of virtualization. The Linux Vserver project is an example of this. The basis of this is the ability POSIX operating systems, such as Linux, have for a process to be “chrooted”, or to run in “jails”. That is, a process can be started in a particular directory, in a manner that it thinks that the directory is “root”, or the top of the entire file system. It cannot even see the rest of the file system, let alone access it. An analogy of this is for a boss of a large company giving an employee access to only one floor of an office block and telling him that the building only has one floor—that one. And him believing it! Each virtual server has a directory—or a floor if you like—and sub directories (offices) containing the necessary programs and configuration files required for it. For each “floor” a master process is created and “chroot”ed into its very own directory, and all services for that virtual server—such as web and email—are “forked” or started by that master process, thus inheriting the same restrictions. This means that each virtual machine can run its own web, email, ftp and database server independently. However, they share the same kernel, so as with the “Virtual Host” model, their is no performance hit in the virtualization itself. Each virtual server owner does have the benefit of much more control over their own “server” by comparison with the “virtual hosts” above, in so far as they can install and configure their own software. Although the control is often enough, it is not extensive. As a “virtual server” owner, it is difficult to configure your own firewall, and there is no way to mess about with the kernel or its parameters either. And you still can’t change the time.

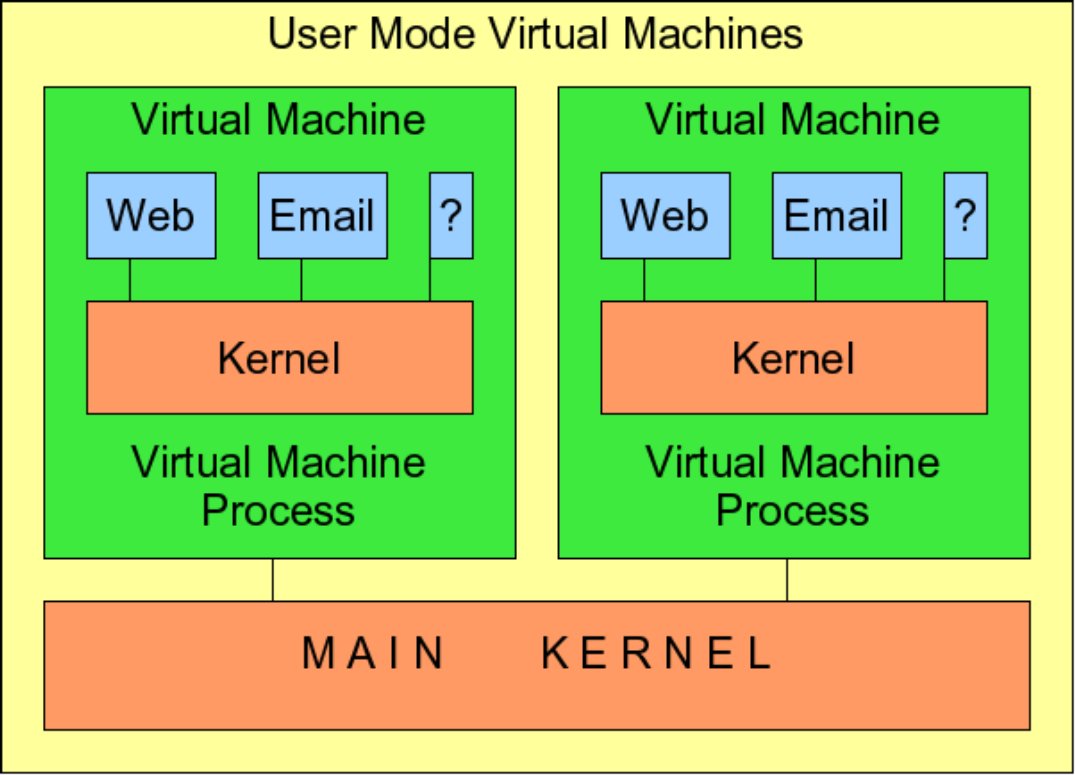

3. User mode virtual machines

An example of this is User Mode Linux. Here, certain resources, such as the amount of memory, disk space and so on, are assigned to each machine in a configuration file. The main machine, or “monitor”, fires off a process for each virtual machine. This process is a wrapper that runs a kernel resident on the virtual machine itself. This means that the owner of each virtual machine has, more or less, complete control of that machine, down to which kernel is used.

Virtual hosts have low administration overhead, Virtual Servers have more virtual functionality, both enjoy minimal performance hit, neither offers complete virtual control

Functionally, it is almost identical to having your own co-located real machine, with the added benefit of the web hoster being able to provide a special URL where you can SSH to perform administration tasks such as rebooting and grant you access to your virtual system consoles. Also, finally you can change the time on your virtual machine! All of this comes at a price however. Your virtual machine’s kernel is in fact running as a user process on the master machine. This means there is a severe performance hit in the virtualization itself. Although this is often easily counteracted with fast hardware being relatively cheap, it none the less is an unwelcome attribute. On a side note Cooperative Linux also falls into this category, this is where you can run a number of Linux virtual machines as processes on a master Microsoft Windows machine.

4. Emulated virtual machines

I am thinking specifically about products like QEMU and Bochs. This type of virtualization, or emulation, is unlikely to be used in a web hosting environment, which is the crux of this article, but more in a development type installation where more than one operating system needs to be run. However, I am including it for completeness sake. This operates in a similar way to the “user mode virtual machine” described above except that the “wrapper process” the master machine runs is, in this case, more of a hardware emulator. This allows for more diverse uses of the virtualizing features, such as the ability to run Microsoft’s Operating Systems and Linux Systems, in separate virtual machines, simultaneously. The advantages of this is its versatility, the disadvantage is that it suffers a major performance hit in its virtualization, or emulation, process.

Virtual Machines offer the functionality and more of a co-located machine for the price of a virtual host though at a performance cost

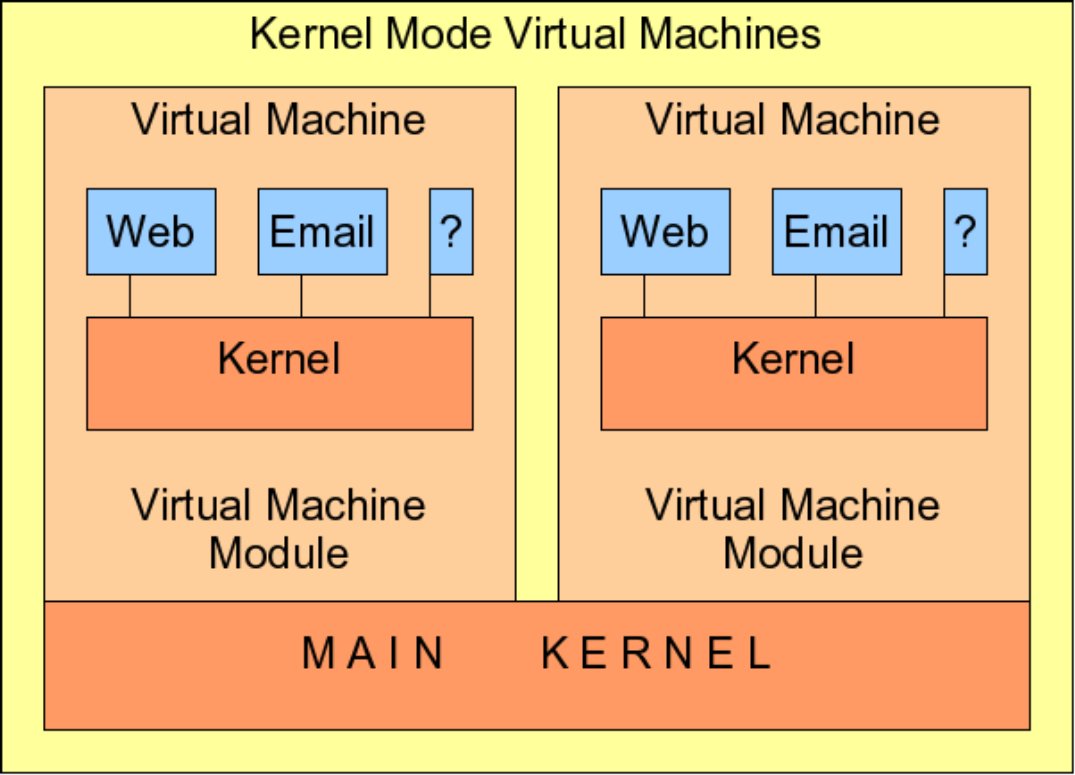

5. Kernel mode virtual machines

This is Xen, and what I am so excited about. The overall concept is similar to the “user mode virtual machine” described above. However, in this case, the “wrapper process” is not a user process, but is built into the kernel of the master machine. This means that all of the advantages of the “user mode virtual machine” exist, but there is hardly any performance loss from the virtualization process. In short, a process running on a virtual machine runs almost as fast as a process running on the main machine itself. Also, in Xen, it is possible to control further resources on the virtual machines more easily, such as the number of processes to use for each node and so on.

Xen is still in its infancy, even so, distributions are beginning to ship it as standard, and web hosters are beginning to put their toe in the water to see how well it will do (the Xen software that is, not the toe). First impressions are that it is performing well, and I believe it will soon be seen as a standard option for web hosting. This, I believe, will have major implications in the web hosting market. No longer would an owner of a web hosting company choose between “virtual hosts with not much virtualization” and “virtual machines and a major performance hit”. The virtual machine no longer has that performance hit! More memory may be required, but that is now a minor investment. This also enables hardware costs to be consolidated into large “big iron” servers. Therefore, virtual machines could outperform dedicated co-located machines by several factors but be supplied at a tiny fraction of the cost. To run that passed you again, currently you can get the functionality of a co-located machine, as well as administration features, for the price of a virtual host. Soon, I believe, you would not only get the functionality and the administration features, but also the performance of one. In fact, it would not surprise me if the norm was for a cheap virtual machine to significantly out perform a far more expensive dedicated co-located machine. I believe the distinction between network and machine will not only be blurred and obfuscated, but will be totally and utterly distorted.

Xen—Kernel Mode Virtual Machines—means that now not only can virtual machines match usefulness and performance of dedicated ones, but they can also outmatch them

Conclusion

Few of us can justify the cost of having our own machine, even a co-located one. The vast majority of us who have web sites use one kind of virtualization or another. The type most used is the “virtual host”. This is the one that most of the web hosters provide, and is the one currently the easiest for administrators and end users to administer. However, technology over the internet is exploding. New innovations are being implemented daily—if not hourly! Where they didn’t start as free software, versions of them are being written. Often, simply having a “virtual host” is not sufficient to benefit from the innovations. New web hosting companies—as well as some old ones—have smelled the coffee and are providing virtual machines at what would, in the past, be considered as idiotically low prices, often giving functionality and performance far greater than that of an expensive dedicated machine. For those stuck in a “virtual host” who want to make use of this new technology it is time to bite the bullet, grit your teeth, put on your running shoes, pull your socks up, place your inhibitions to one side, charge in and make that leap.