Space is open to us now; and our eagerness to share its meaning is not governed by the efforts of others. We go into space because whatever mankind must undertake, free men must fully share.—John. F. Kennedy

The beginning of this series presented the motivations behind creating a protocol for creating a free-licensed design marketplace for material products. Now, I hope to detail the design concept of a specific package: “Narya Bazaar”[1] is to be a web e-commerce application designed for a free-licensed economy. It will need to have many features in common with other e-commerce systems (shopping carts, credit card payments, and so on), but here I want to explain the unique part of the design, which is the “Bargain Protocol” that links our three principle actors: projects, donors and vendors.

Actors

Projects in the Narya system are more-or-less as they are in the GForge2 free software project incubator. They may be run by single individuals or groups of people. Groups might be affiliated only through common interest, or be co-workers funded by a commercial institution, though the former is much more likely.

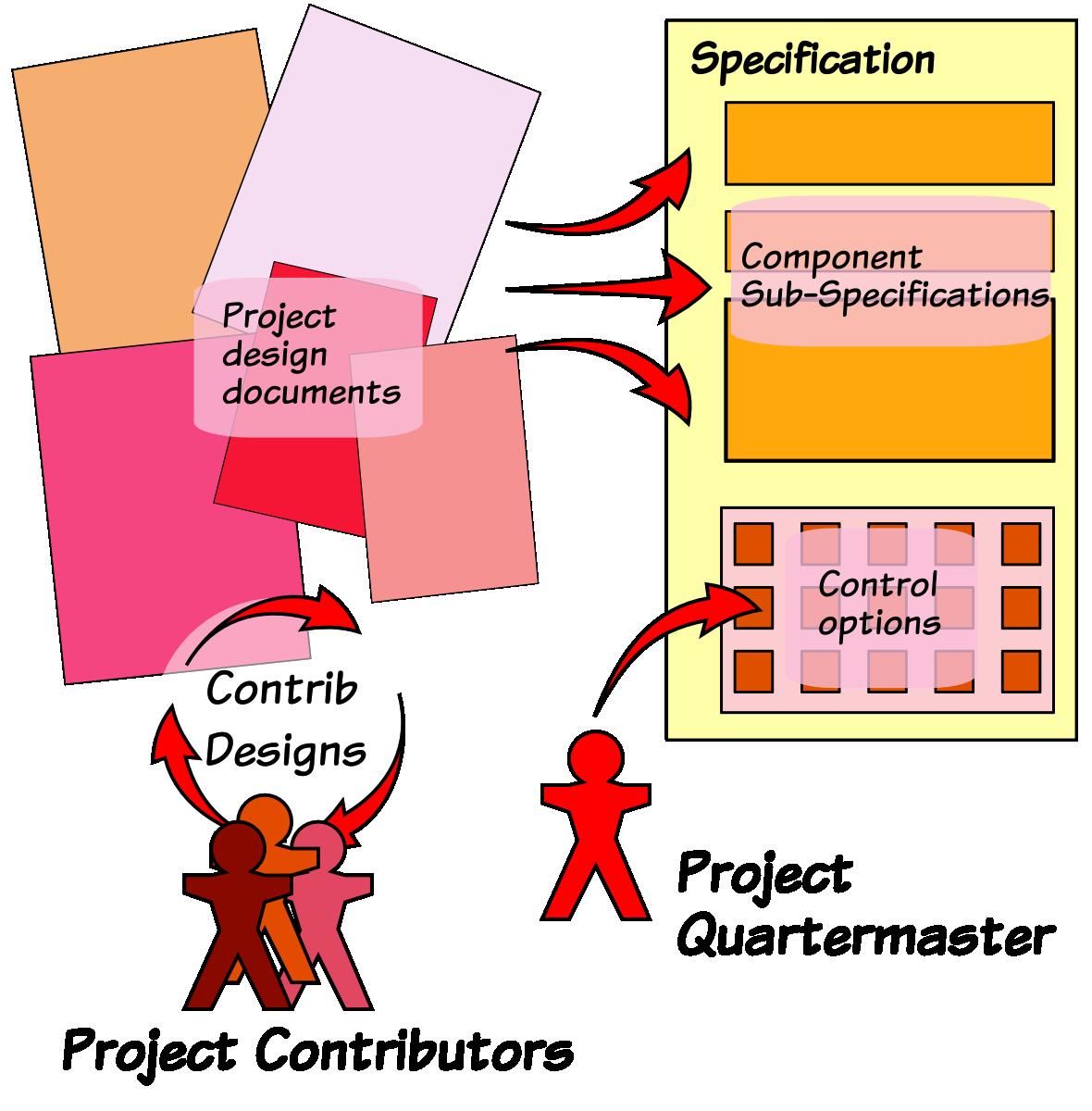

There are particular roles within the project that are common to other project systems, such as the “project leader”, but Narya Bazaar introduces another particular role, which I call the “quartermaster” (QM). Like a real quartermaster, the project QM is in charge of the project’s material stores, and is trusted by project members with this role. Furthermore, in order to interact with the Bazaar system, the QM must have a physical mailing address and account information on file at the site. Since this represents some loss of privacy, it’s understandable that projects will not want all of their members to have to agree to these terms, but at least one member needs to if they want to take advantage of Bazaar’s provision of materials and services.

Like a real quartermaster, the project QM is in charge of the project’s material stores

Donors, are the wonderful people who have money to spend on seeing that projects of interest to them succeed. Without them, of course, there would be no point in designing Bazaar at all. We do not treat them as a magic source of funding here, however, but as customers who expect to see value for the money they contribute. This value comes in the form of newly available technologies that they can use, and in the manufactured incarnations of those technologies as provided by vendors.

Finally, vendors, are the commercial providers of the materials and services that are needed by projects to complete their development work, and who must be paid using funds that come from donors. These are fairly well-understood commercial entities, although they may take any commercial form from a self-employed consultant to a large contract manufacturer or commodity supplier. In some cases, the “vendor” in the Bazaar system will actually be a reseller of services procured by external means.

Vendors sell to donors in essentially two modes: the first is direct sales in which the “donor” is more-properly called simply the “customer”; and the second is providing services to projects that the donor is supporting. In a successful free-matter economy, the former kind of sale will dominate in sales figures, although the latter will probably be the main form of sale at the beginning, and may always be the largest in number of unique transactions. However, since the former case is handled by standard e-commerce solutions, I will not expand further on it. It is the latter mode that most needs explanation here.

Project needs

In the previous two articles, I have outlined the fears and needs of the donors and vendors by way of outlining the requirements of this protocol. The one remaining class of actors is probably the most obvious one—the project developers. Fortunately, the fears and resulting needs that project developers have from the Bazaar system are pretty straightforward:

Funding

- Fears: that project will be impossible to complete because of materials costs.

- Wants: a fundraising system that allows interested parties to help them with costs.

This is the whole point of the Bazaar system.

Services

- Fears: project will require work that participants are unable to do for themselves.

- Wants: way to purchase necessary services.

In short, we need to have vendors available to provide the services. Given the difficulty of sourcing, ordering, and receiving high-tech components in prototype quantities and the difficulty of finding testing services which are normally only marketed to commercial organizations, this would be a problem even if money were no object.

Commercialization

- Fears: commercial needs will overwhelm project participants and steal control of project goals.

- Wants: to control project without the threat of “takeover” by donors or vendors.

Project developers have chosen the free-design route for a reason. Any design which tends to destroy the free-market of ideas surrounding free-licensed development must be avoided. Although Bazaar will undoubtedly include a “tip-barrel” much as SourceForge now does, the focus will be on “provision” funding rather than “grant” funding for this reason (projects wishing to operate on a direct-payment basis can always function as vendors in the Bazaar system, of course).

Combined with the needs outlined in parts 1 and 2, this gives us the requirements that drive the design of the Narya Bazaar Bargain Protocol.

CMS and design tools

Most project developer needs are not for the funding system described here, but the content creation and management systems that will be needed to collaborate with developers on a global (or even interplanetary) scale. Fortunately, this is one area where there is much support from the free software world already.

In the simplest case we could simply use the GForge application (the free branch of the SourceForge web application). Or we can extend upon any of a wide variety of CMS systems. For Narya3 I have chosen to develop a content system based on Zope[5], which provides very useful structural abstractions for the job. I’m hedging my bet though, by providing “application views” that allow me to window other services inside the Narya framework. This would, for example, allow running GForge at least as a transitional measure.

Unfortunately, there are some gaping holes in the available free design tools for serious hardware design. I hope to cover the most important ones in the next installment of this series.

Resolving trust faults

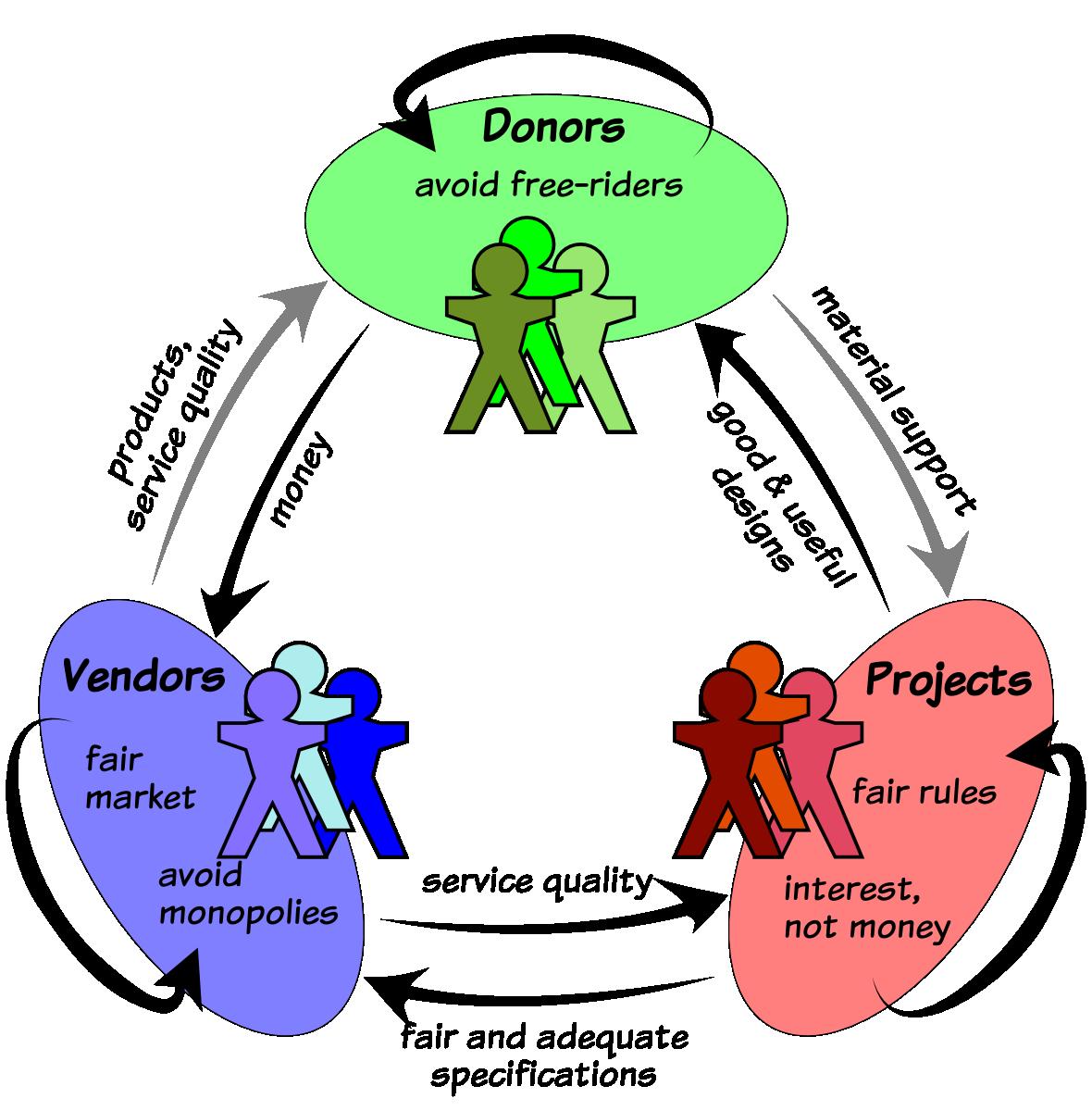

Most of the needs outlined for these three actors are types of assurances that need to be made to resolve the natural trust faults of the bargain arrangement, as diagrammed in Figure 1. Note that faults exist not only between the classes of parties involved in the bargain, but also among the individual actors within each group. Indeed, these include some of the most serious problems to be solved.

Most of the needs outlined for these three actors are types of assurances that need to be made to resolve the natural trust faults of the bargain arrangement

The “free-rider” problem is the classic “tragedy of the commons” problem, in which donors fear that other donors will not “ante up” to support projects that they do, thus resulting in wasted funds. On the other hand, if the donor has some assurance that their contributions will leverage or control other people’s contributions, they will be more likely to spend (since there is an amplification of utility involved). Naturally, of course, such control of others’ funds must not exceed the willingness of those others to participate. There are proven methods of solving these problems, such as “matching funds” and “spending caps”. In fact, there is an electronic protocol called the “Rational Street Performer Protocol” (RSPP)[6] which seeks to maximize funding from such sources, using conditional pledges. These pledges outline the basic facts about a particular contribution: an amount the donor is willing to spend unconditionally, a fraction indicating how much leverage they want to insist on, and finally a cap on how much they can afford to spend.

The internal problems among vendors are the same old problems as with all commercial free-markets. Essentially the playing field must be kept level enough, and individual players have to be kept from monopolizing the field through winner-take-all tactics. Furthermore, there must be penalties for rule-breaking to keep dishonest businesses out and to protect the honest ones (as well as to keep them honest). In an electronic marketplace, anonymity and distance heighten the threat of fly-by-night operators, so a means of automating the word-of-mouth knowledge that protects smaller communities is needed. Fortunately, good examples of this kind of strategy can be found in pre-existing applications including moderated forums and E-Bay’s rating systems[7].

The “free-rider” problem is the classic “tragedy of the commons” problem, in which donors fear that other donors will not support projects that they do

Projects have similar problems to vendors in terms of ensuring fair competition, even if money is not involved. Fair assessment of projects on an objective basis, and fair sharing of site resources are necessary to avoid conflict and avoid losing projects from the system.

The most complex trust fault in the system, however, arises from the problem of paying for goods to be manufactured. It takes irrecoverable time and energy to manufacture a good or provide a service. Payment in advance would solve this problem for vendors, but for donors, the problem would then be reliance upon vendors to deliver the requested product or service at a service-quality level that is appropriate for the money paid. Market forces will tend to force vendors to cut corners, and shoddy work may result if no direct feedback on service quality is provided. Again, however, there is a standard solution to this type of trust fault: an outside party, trusted by both sides can be chosen to hold the funds in escrow while the transaction is being completed. This provides assurance to the vendor that they will get paid if they deliver, but also assurance to the donor that payment will not be made if quality standards are not met. This introduces a new actor: the “Quality Assurance Authority” (QA).

Fair assessment of projects on an objective basis, and fair sharing of site resources are necessary to avoid conflict and avoid losing projects from the system

Specifications

Relying on quality assurance for payment, however, does of course increase the burden on the vendor to ensure that there are objective QA tests that they can pass. This in turn requires the project to provide unambiguous specifications and tests. Hopefully, developers familiar with “test-driven development” will find this a tolerable requirement. It also, of course, makes sense in terms of the project’s own reliability needs.

In order to clarify the process of creating these specifications, and to show that it is feasible to provide automated means of doing so, it’s necessary to segment the possible types of specifications that I anticipate. Naturally, all of these categories are really “services”, but there are policy and delivery issues unique to each:

- A general service spec requests a certain service such as professional (certified) engineering review or design-to-requirements be done for the project. Other examples include: simulation, computation services, and programming or documentation. The product falls under the project license as a work-for-hire and will be subsumed into the project.

- A standard service spec requests services which can be quoted automatically, such as notary services or engineering review of standard types of designs. Prices might be flat-rate or based on easy-to-measure factors such as “number of plan pages”, etc. Terms are otherwise the same as for a general service.

- A manufacture to plan spec requests that a project design be built to the specified plans and tolerances. The vendor assumes no responsibility for functionality, only that the manufacturing was done as specified. Since the design is the project’s, free-licensing is guaranteed and prior-art precludes patentability (assuming it was not previously patented).

- A manufacture to requirements spec requests that a product be made to meet certain functional requirements, but the implementation is left up to the vendor. In this case, the licensing is controlled by the vendor, within whatever vendor licensing policy is in effect on the site.

- A standard manufacture spec, like the standard service spec can be quoted automatically, but is otherwise similar to plan or requirements manufacturing. Examples include electric motors, gears, printed circuit boards, etc. Vendor warrants performance because design uses standard practice. Licensing is generally a non-issue because either the product is too standardized to be proprietary (e.g. a spur gear), or proprietary aspects of the design are hidden behind standard interfaces (e.g.electric motor).

- A standard supply spec is for a standardized part that is probably already stocked, such as discrete electronics, standard sized pulleys or belts, or even a whole personal computer. Note that in later generations of the Bazaar, a free-licensed design may be offered by vendors as a standard part in this way.

Each type of specification has particular special behaviors in the system from either the vendor or the project perspective. For example, prices on supply specs are likely to be fixed in bulk, and “standard” specs will probably allow vendors to provide scripts and standard specification content objects—the scripts would inspect the content object for the necessary information and generate a quote automatically.

Each type of specification has particular special behaviors in the system from either the vendor or the project perspective

Fuzzy MRP

Manufacturing resource planning (MRP) is the process by which companies try to control the costs and timescales associated with manufacturing parts which are made of parts which themselves must be manufactured or purchased, and so on. If properly done, MRP allows for “just in time” manufacturing and very reduced needs for warehousing space.

MRP for a free-licensed matter economy, however, introduces some special challenges, since the agents producing each component of a product are not internally controlled by any one organization. Instead, the application of market forces will determine estimated production timescales and costs. In all probability, this will actually be more efficient than centralized manufacturing in the average case; but the worst case scenario cannot be so easily constrained.

Fortunately, the Bazaar’s bargain transaction database should provide some basis for making statistical predictions about the time to deliver on particular products and services, and allow estimates to be made for new ones based on that data. Since times and costs will be tracked, it makes sense to think that predictions can be made in this way. Adapting MRP[8] systems to handle the intrinsic fuzziness of bazaar-type marketplaces will probably be an interesting challenge.

Finally of course, the higher levels of involvement of general services allow for involvement as extreme as writing pieces of software or designing major system components on a for-pay basis, to be incorporated into a free design. This is a likely place to find a “project acting as vendor” in the system—Bazaar will place no restrictions on users playing multiple roles, although when acting as a vendor one must follow vendor rules, and so on. In the interest of avoiding scams, such multiple-role cases will likely be flagged so that it is clear to all participants what is happening.

MRP for a free-licensed matter economy introduces some special challenges, since the agents producing each component of a product are not internally controlled by any one organization

Transactional specification

In addition to providing the above segmentation of specification types, it must also be noted that specifications will usually be multiple, with bargains requiring all to succeed in order for any to proceed (that is, they are “transactional”). There are two major use cases for this:

- Build and test—the cases where the QA can verify delivery by simple visual inspection are probably rare. In order to provide a meaningful assurance of quality, he will need to test data results. So for example, a critical welding job might need to be sent to a lab for X-rays, or a less critical one might simply need to be inspected by a trained welder. The QM must carefully determine what tests will be done, as they will be the main assurance of quality.

- Shopping list—for many jobs, there may be a need to collect a long shopping list of components. Clearly if they can’t all be purchased, just buying a few is a waste of resources. So, all of the components for one job might be combined into one transactional specification.

Placing a specification up for bid will be a task for the project QM, although she can obviously be assisted by other members of the project to clarify finer points. The specification will be created out of existing project content objects, designed to be adequate to the purpose.

Specifications will usually be multiple, with bargains requiring all to succeed in order for any to proceed

In addition to the individual specifications, the QM will have additional options available to her. The most important is probably the choice of QA authority to administrate the bargain. Clearly it must be someone that both potential vendors and project members trust. Choosing to let the QM or the prospective vendors themselves act as QA is also possible (and probably cheaper), but it clearly has certain risks. Another factor is the length of time to allow the bargain to continue—all bargains will have a finite time-limit, and whether the bargain should terminate as soon as a solution is found, or wait to see if a better deal is offered before the deadline runs out (is speed or lower price most important?). Other parameters include how fast delivery is to be made, what form of shipping is to be allowed, and so on.

Vendor constraints

One objection to this type of system is that it makes price the only factor in determining who gets a contract. This could result in poor quality standards, even with QA inspection. Since a system for rating vendors is envisioned, however, it seems reasonable to allow projects or donors to apply constraints on whom they are willing to do business with. Vendors below a certain rating might be rejected due to questions about their quality of service or sales practices, allowing a “reputation game” to exist among vendors.

There are other reasons for restricting vendors, too, such as shipping costs or customs problems. It may be desireable to ensure that a product will only have to be shipped within the QM’s home country, for example, or even that it is available from a supplier close enough for the QM to pick it up in person. Or, the supplier may have to provide particular shipping options suitable to the QM.

There are other reasons for restricting vendors, too, such as shipping costs or customs problems

Such a constraint system will need to be used by the QM when putting the specification up for bid.

Bargaining process

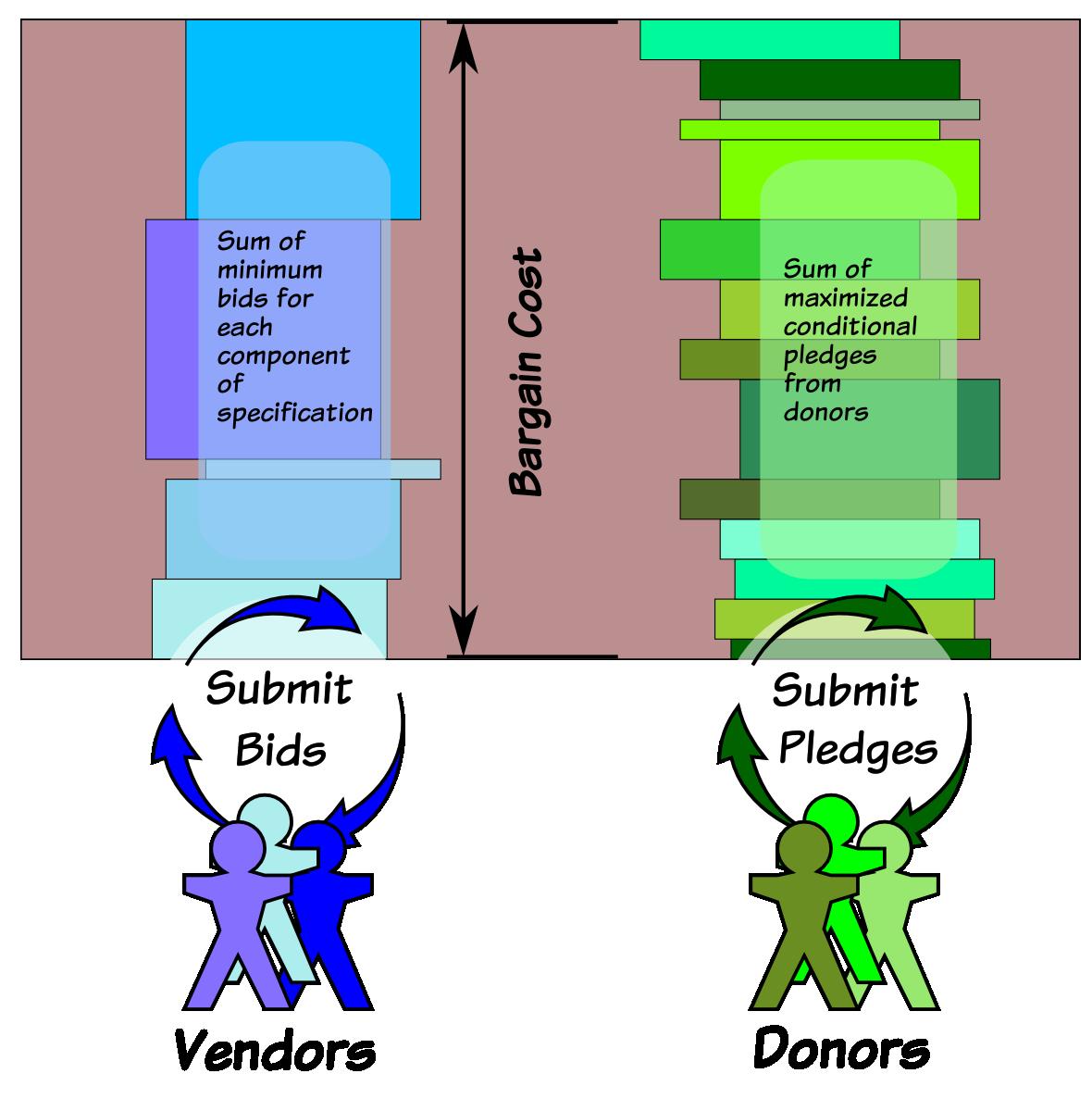

Once the specification has been created to the QM’s satisfaction, the bargain can proceed to bid. The strategy is a kind of “reverse auction” where vendors provide bids on each sub-specification (and possibly more than one if spec constraints allow it). As soon as at least one bid exists for each part of the spec, a “bargain cost” is established. After that, subsequent bids may lower, but not raise the bargain cost.

Meanwhile, RSPP pledging is allowed to start as well, so that donors can pledge support for the bargain. These are summed following a modified version of the original RSPP fund-raising algorithm. Pledges, once made, are not withdrawable until the bargain ends, so the available money to meet the bargain cost can go up, but not down.

Pledges, once made, are not withdrawable until the bargain ends

Both bidding and pledging continue at least until the available funds match the bargain cost. Calculations may be complicated a bit by constraints placed by donors on vendor-qualifications, since if a vendor is questionable to one donor, we have to consider both the solution without that donor and the solution without that vendor. Essentially, however, this is a simple comparison of two sums (see Figure 3).

If the QM has opted for “close on solution”, the bargain will end early if a solution is found. Otherwise, the bargain will persist until the prescribed deadline, waiting for the possibility that another vendor will underbid one of the current vendors in order to capture the contract, possibly reducing the cost.

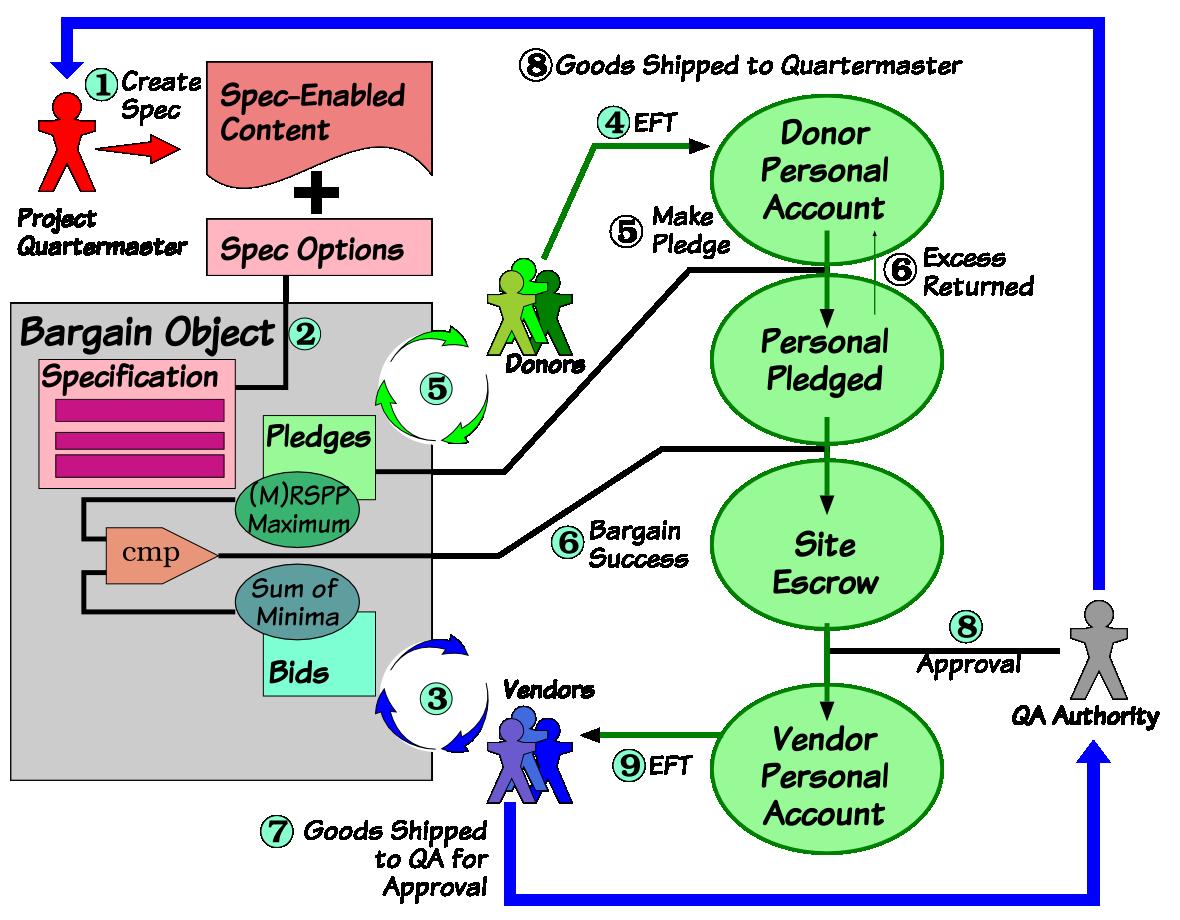

Quality assurance and delivery

The entire bargain protocol is summarized in Figure 4, which also shows the final steps taken once the bargain succeeds, as well as the flow of cash through the system. As soon as pledges have been made, an estimate of the maximum pledge amount is locked from the donor’s account to avoid potential overdrafts. If and when the bargain succeeds, the actual amount for each pledge is computed (using a modified version of the RSPP algorithm that avoids overshooting the bargain cost), and moved into a site escrow account reserved for this bargain. Any excess “pledged” money is returned to the donor’s account so they can use it elsewhere.

At this point, notices are sent to all parties that the money has been escrowed to pay for the contracted services. The vendor is cleared to begin work on delivering the order. As each vendor completes their work, the QA is notified and the project proceeds to the next vendor (if sequenced processing is required, otherwise all components can be processed in parallel), possibly requiring a shipping step. Finally, when all stages are complete, the QA receives all material and documentation results. Assuming that QA standards are met (e.g. tests confirm that the work is acceptable), then the QA releases the escrow, allowing all of the vendors to collect their payments. At the same time, the QA ships all product materials to the QM.

At this point, the QA collects a small transaction fee from the sale to compensate them for their service (this fee is included in the bargain cost computation and is advertised by the QA to the QM who chose him). Collection of QA transaction fees is one means by which a Narya Bazaar site owner might make revenue.

What if it didn’t work?

One of the other options for the QM is to constrain what sort of remedies are available if a product or service fails QA testing. In the worst case, the service is rejected, the bidding cycle must start again, and the vendor absorbs a loss. This is bad for the vendor, but is clearly the right behavior for critical components.

In the most lenient case, the QA may notify the QM of the problem, allowing the QM to accept the product anyway. At the same time, the vendor would be given the same information, with the option to rework the product or service to try to bring it up to spec.

One of the other options for the QM is to constrain what sort of remedies are available if a product or service fails QA testing

Clearly, there are other possibilities which can be resolved between the QA, QM, and vendor before giving up completely, but if all else fails, the bargain is rejected and must start again. In that case, funds are released from escrow back into the donors’ accounts. As a special exception, it might be possible to allow the bargain to revert to “open” again if its time has not yet expired (but this can only happen in the “close on solution” case).

A similar situation occurs if no solution is found before the bargain’s closing date. In that case, funds simply revert to the donors, and it’s up to the project to revise their specification to see if they can make it more attractive and try again.

Expediting the bargaining process

Given that many common classes of specification can be bid on automatically, it should be possible for the bargaining system to approach the simplicity and speed of a standard “shopping” or “requisitions” experience for some transactions, while retaining the flexibility to deal with more complex manually-quoted contracts. At least this will be so if adequate suppliers are available, and the investment is made in automated bidding scripts. Competition would occur through the proxy of the automated agents created by vendors. Many strategies are possible for maximizing the utility of this system, and it assures lower overall prices than can be expected from a standard “e-store” system. For common cases, the risks may be low enough that the reduced cost and greater convenience of allowing the vendor or project QM to act as QA will be desired, eliminating QA costs and double shipping.

The shape of things to come

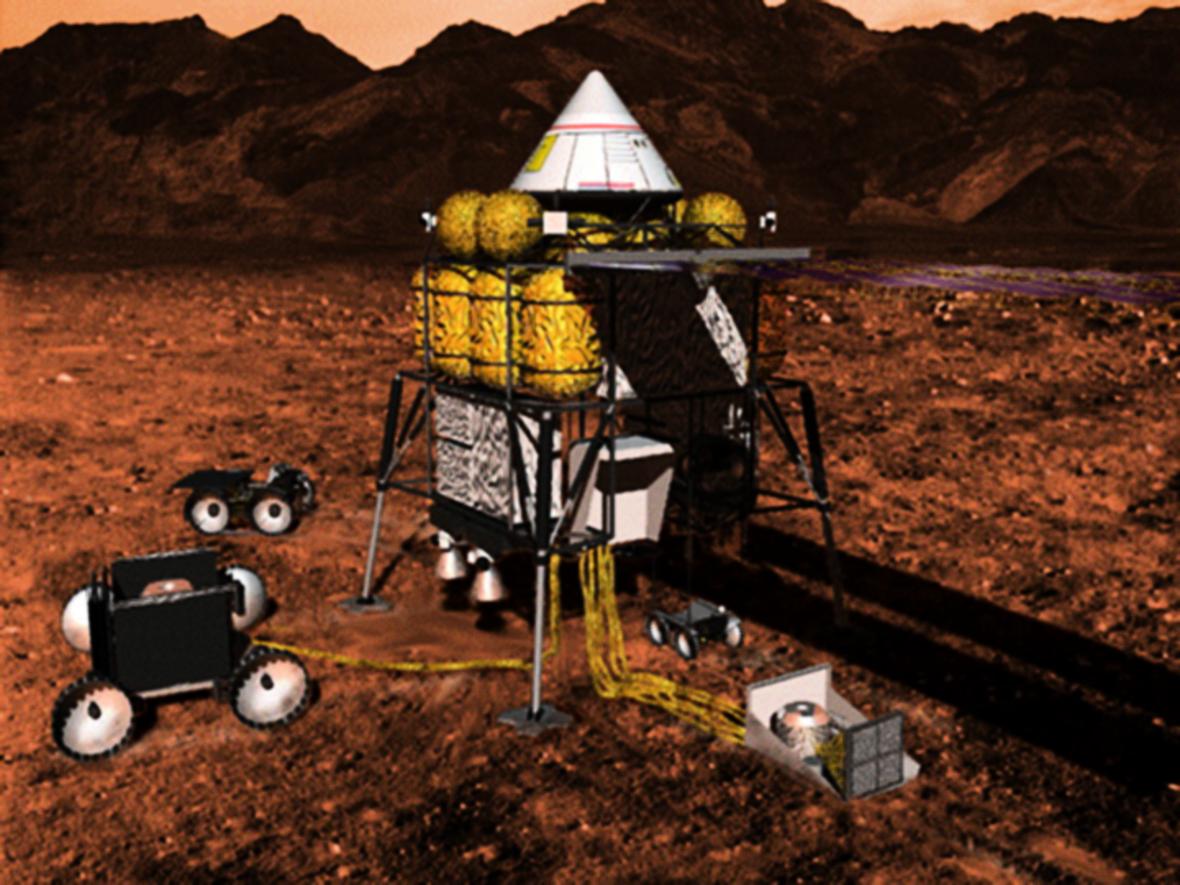

The future economy will deal with many realities that contrast with today’s close knit ship-to-anywhere world, especially as we move out into space. Present models for colonizing Mars, for example, rely heavily on concepts of In Situ Resource Utilization (ISRU), or “living off the land” as Dr. Robert Zubrin called it in The Case for Mars9, in order to avoid impossibly high expense. At the same time, there is a rising interest in commercial space development and dissatisfaction with today’s government subsidized programs, which do seem to be very stagnant. But how does ISRU work in a free market economy? The very nature of ISRU requires that products be manufactured on site, with manfacturing localized to the end-user (possibly done by the end-user). This is in stark contrast to our e-commerce mail-order economy where manufacturing localization is regarded as irrelevant, and it forces the question, “what will be sold by free market entrepreneurs in this coming interplanetary era?”

Which rules are we more willing to live by: those of _intellectual property_ or of _intellectual freedom_?

Clearly the delivery will not be products so much as the information required to make them, and this puts the matter economy on par with the information economy. Indeed, nearly all meaningful trade will be in information, while true material production is localized to the person who needs it, external to the trade economy. This places us in the position of deciding whether we want the hardware design economy to follow the model of the proprietary software giants or of the free-licensed software world. Which rules are we more willing to live by: those of intellectual property or of intellectual freedom?

If we choose freedom, we’re going to have to build the tools to make it work, and create a culture of people who know how to use those tools.

Bibliography

2(http://gforge.org/projects/gforge/)

[6] Paul Harrison, The Rational Street Performer Protocol

[9] Robert Zubrin, The Case for Mars, 1996.

10(http://www.marssociety.org/interactive/art/nasa_charts.asp)