This article compares two development platforms: Java and Mozilla. The object of this comparison is not to establish which one is best, but rather to measure the maturity, the advantages, and the disadvantages of Mozilla as a platform from the point of view of a Java programmer (as I am). Such a comparison is not a speculative exercise but it is the result of a process of technology scouting that I have performed during the last months with the objective being to find more effective tools, languages, and patterns for the development of distributed, pervasive, and location-aware internet applications. The article briefly introduces Java and Mozilla, and then points to similarities and differences. A detailed analysis of some important programming domains such as GUI, multitasking, remote applications, community process, and development tools are presented together with a comparison of functionalities provided by the respective API.

A short introduction to Java

Java is a multi-platform object-oriented language. In other words, you can use constructs and patterns of object-oriented world to write programs deployable in different operating systems without changing a line of code and without “recompiling”. Although this is quite common for interpreted languages, the Java code is not interpreted. Java compilers build binary code called bytecode, which is loaded and executed by a virtual machine, independently upon which the operating system is running in the “real” machine. Thus, a bytecode compiled under Windows can be loaded and executed by a virtual machine running on Unix. The Java virtual machine hides underlying system-related details and it is provided with a unified API, common to all platforms. This implies that only the functionalities that are common to all platforms can be exploited by Java programs. The idea of “virtual machines” is not a new one; older languages such as Smalltalk introduced this solution years before Java, but as often occurs, the best and the first are not automatically the most successful.

If the portability of bytecode is one of the key features of Java, another important feature is that at the beginning of its life Java was considered the “language for the web”. This was due to Applets—programs that can be downloaded and executed inside a web page. Since its birth, both of these features of Java have revealed their limits. On one hand, bytecode portability assumes that the footprint of different machines is equivalent: loading bytecode compiled for a desktop PC in a PDA or to a cellular phone is in general not possible. On the other hand, Java Applets have gained less success and diffusion than other competitor technologies such as Macromedia Flash. Nevertheless, Java has gained a huge popularity among research teams and also for proprietary software. Among the most noticeable applications are the tools for Java programming written in Java. Moreover, to extend the adoption of Java in small footprint devices, different “editions” of the Java platform were created: J2SE is the Java 2 standard edition virtual machine for the desktop computing and personal system applications; J2EE is the enterprise edition which comprises server side components such as Servlet and Enterprise Javabeans. The J2ME profile aims at small devices such as mobile phones and embedded systems. For a complete classification of Java virtual machines and API please refer to Java’s web site [1]. In the domain of web applications, even though Java applets lost the war against Flash on the client side, things evolved favourably to Java technology on server-side. The J2EE provides a robust framework for secure and scalable applications competing with the ASP and PHP technologies.

One of the success points of Java is its technology pervasiveness. Java programmers “make themselves at home” in a vast range of domains: they can write stand-alone programs, application plug-ins, applets for web pages, web applications either in the form of servlets (Java code which embeds HTML tags) or Java Server Pages (HTML which embeds Java expressions), and Enterprise JavaBeans which build the application logic in multi-tiered architectures. Furthermore, Java scales the OOP paradigm to distributed systems by means of RMI (Remote Method Interface) and Jini (a framework which makes a deep use of code mobility to build dynamic collection of distributed services). In the domain of “small footprint” devices, Java has its JVM tailored for cell phones, PDAs, and smart cards.

One of the success points of Java is its technology pervasiveness. Java programmers “make themselves at home” in a vast range of domains

A short introduction to Mozilla

Mozilla is not a language. It is a known free software suite of internet clients. However, looking under the hood, you can discover that Mozilla is not only a browser and a messenger, but it is a platform with a complete component-based architecture. You can develop new stand-alone programs, add-ons for the browser, and code that can be loaded from remote hosts.

The Mozilla project has quietly become a key building block in the open source infrastructure. (Tim O’Reilly )

The most remarkable elements of the Mozilla platform are its component architecture called XPCOM (which recalls Microsoft COM) and the Gecko layout engine, which can render both HTML and the XUL mark-up language—an XML language for the definition of rich (as opposed to poor HTML forms) graphical user interfaces. The entire GUI of Mozilla is written in XUL and rendered by the HTML/XUL Gecko rendering engine.

The XUL approach has produced two main results: Firefox and Thunderbird. Aside from these two software masterpieces there are hundreds of small third-party add-ons, which cover any possible requirement of final users.

Firefox nudged IE below the 90 percent mark for the first time since the height of the browser wars in the 1990s. (Ina Fried and Paul Festa [3])

It is worth noting that Microsoft is likely to adopt a XUL-like solution for its Longhorn operating system. The Microsoft solution consists of an XML language called XAML for the definition of graphical user interfaces integrated by C# scripting [4].

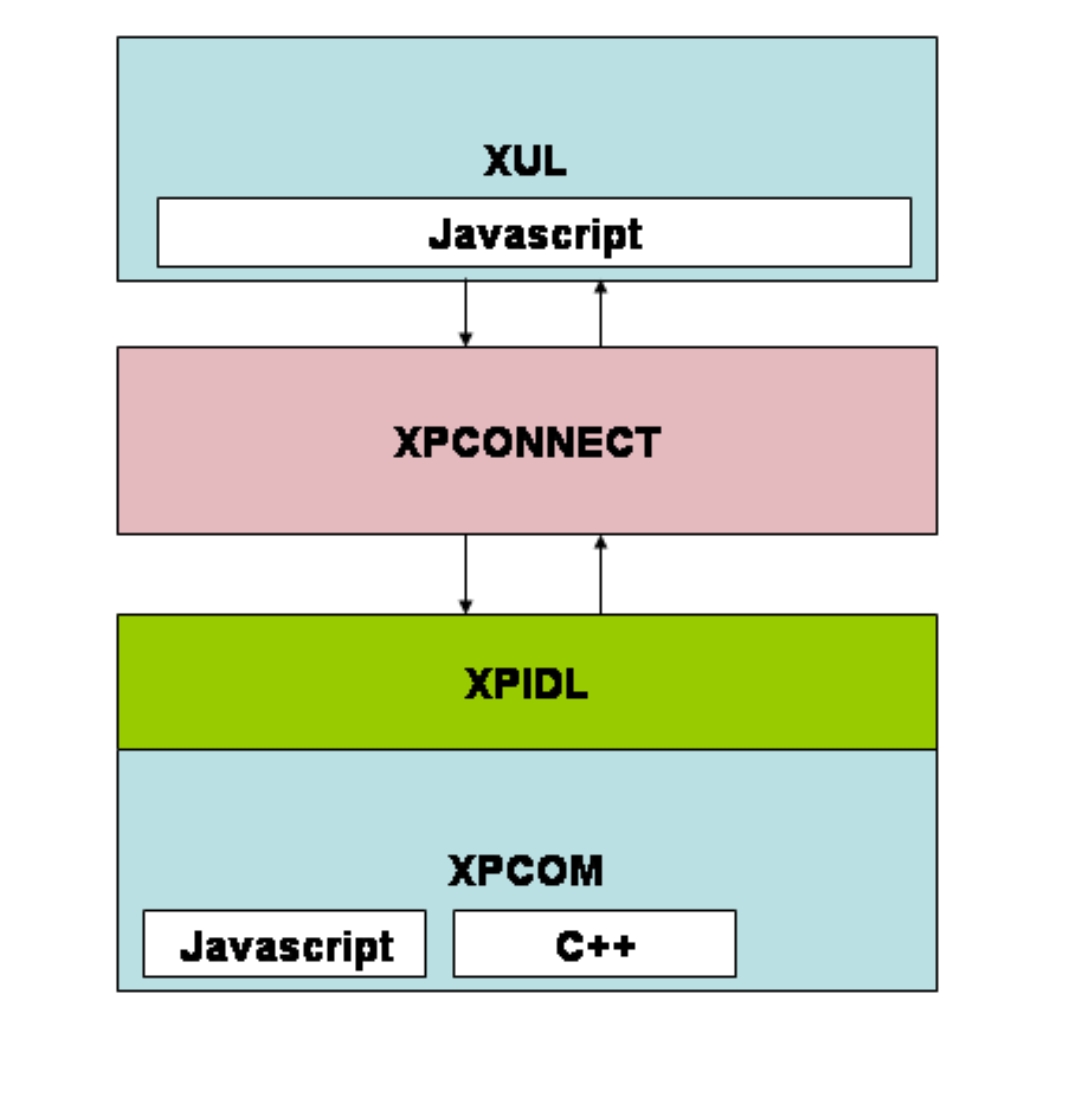

Differently from Java, Mozilla does not define a unique programming language. According to its philosophy, Mozilla exploits the best (or the worst, depending on the point of view) of existing languages and adds its own dialects. XUL is not a programming language but rather a GUI description language; events in the GUI are handled by Javascript scripts which can connect to the XPCOM architecture using the XPConnect bridge. New XPCOM components can be developed in both C++ and Javascript and their interfaces are defined by means of XPIDL which is the Mozilla dialect for IDL (Interface Description Language). Data sources and configuration files are written in RDF. Finally, although XUL is used to define the structure of user interface, the final visual appearance is defined using CSS.

Mozilla implements W3C standards and its architecture reflects this acquaintance giving a running environment and a framework in which processing HTML, RDF, CSS and connecting to HTTP servers is almost a “primitive” functionality. On the other hand, Mozilla is mainly an internet-client platform and it does not pervade other domains. So the only possible comparison is with the Java Standard Edition in the domain of desktop applications.

Differently from Java, Mozilla does not define a unique programming language. According to its philosophy, Mozilla exploits the best (or the worst, depending on the point of view) of existing languages and adds its own dialects

Similarities

Classes are a central concept in Java. Any Java project is a set of classes (and other files like properties and resources), and even the entry point of a standalone program is a class containing a method called main().

>java -cp $(CLASSPATH) bar.foo.MyClass

where MyClass “must” implement a method called main().

Similarly Mozilla can be launched and instructed to load a special kind of XML document using a protocol called “chrome”. The usage is:

>mozilla -chrome chrome://chatzilla/content/chatzilla.xul

The result is the opening of an application called ChatZilla without opening the Navigator window.

One of the characteristics of Java is the portability and the mobility of bytecode. This allows the deployment of Java applications in the form of applets. In other words, applications that are downloaded in the context of a web page and that can run using a portion of the web page as display. The receiving browser must be powered with an internal or external JVM to execute the bytecode.

In a similar way, you can write a XUL application for Mozilla, and publish it on a web server. A Mozilla browser can download the XUL file from the network and execute its code. A remarkable example of remote XUL is the Mozilla Amazon Browser [5] and some on line games [6].

The community

The community of Java programmers is huge: there are hundreds of web sites, forums, newsgroups and mailing lists. Java is a successful programming language and Java technologies are governed by the Java Community Process which is open to experts outside Sun. Nevertheless, a large number of hackers and programmers see the FLOSS (Free Libre Open Source Software) as the ultimate model for an open, dynamic, fair, and effective software development and distribution process. This group — the Open Source Initiative — claim that Sun holds the control of Java, and OSI’s popular founder, Eric Raymond asked Sun to “let Java go” [7].

Sun’s terms are so restrictive that Linux distributions cannot even include Java binaries for use as a browser plugin, let alone as a standalone development tool. (Eric Raymond [7])

From its side, Sun advocates its “Sun Community Source License” [8] and claims that the pure OS model has some disadvantages:

- There is no clear control over compatibility issues and there may, therefore, be fragmentation.

- There may be no responsible organization. Bugs introduced by one organization may be too difficult for another organization using it to fix and of too low a priority for the author to fix in a timely manner.

- Progress can be chaotic and have no direction.

- There are limited financial incentives for improvements and innovations, leading commercial developers to use the proprietary model.

The reaction of the FLOSS community to the strict control of Java is the development of new and free software Java platforms such as Kaffe and GNU/Classpath.

Mozilla is the result of opening Netscape to the public giving free access to the source code in the 1998. The first attempt to write a license for the free software community was a failure: the first draft of such a license was published to usenet and received a lot of negative feedback:

One section of the license acted as a lightening rod, catching most of the flames: the portion of the NPL that granted Netscape special rights to use code covered by the NPL in other Netscape products without those products falling under the NPL (Jim Hamerly and Tom Paquin and Susan Walton [9]).

Currently, Mozilla is distributed under MPL/GPL/LGPL triple license, allowing use of the files under the terms of any one of the Mozilla Public License, version 1.1 (MPL), the GNU General Public License, version 2 or later (GPL), or the GNU Lesser General Public License, version 2.1 or later (LGPL). The community was born and raised around the site mozilla.org.

Graphical user interfaces

Java has basically two different GUI toolkits: AWT and Swing. The first one is a bridge between native widgets of the underlying operating system and the Java library. The advantage of AWT is in good performance while the shortcoming is mainly poverty in terms of features and native components. Swing, on the other hand, doesn’t rely upon native components, but instead every widget is rendered by the JVM inside a canvas in the screen. The Swing API is far larger than AWT, and it provides a full object oriented and model-view-control oriented architecture but, compared to AWT, performances are poor.

In the middle between AWT and Swing, there is the SWT library. It provides a rich set of functionalities, and controls with good performance because low-level rendering is performed via C/C++ libraries.

The Mozilla approach is completely different: instead of defining widgets as components of a library in an object-oriented programming language, Mozilla programmers can define a GUI as an XML document.

Mozilla’s philosophy of using “the right tool for the right job” is manifested most prominently in the design of the user interface [10].

So, GUI’s are represented by a tree, and the DOM interface can be used to manage the item in the tree. The XML language used is called XUL and it goes beyond the simple HTML forms giving to the developer a full set of rich graphical components.

Under the hood of Mozilla there is a remarkable piece of software called Gecko which can perform both the rendering of HTML pages and the rendering of the XUL user interfaces.

Javascript, considered by many to be the best scripting language ever designed is ideal for specifying the behavior of your Interface widgets. Where speed is the foremost consideration, we provide C++ libraries with multi-language interfaces for comprehensive, performant access to networking, filesystem, content, rendering, and much more [10].

In fact, there are many browsers based on Gecko, some of them like Mozilla Navigator and Firefox use Gecko to render both GUIs and web pages, while others like Camino uses Gecko only for web pages while the GUI is rendered with Cocoa GUI toolkit.

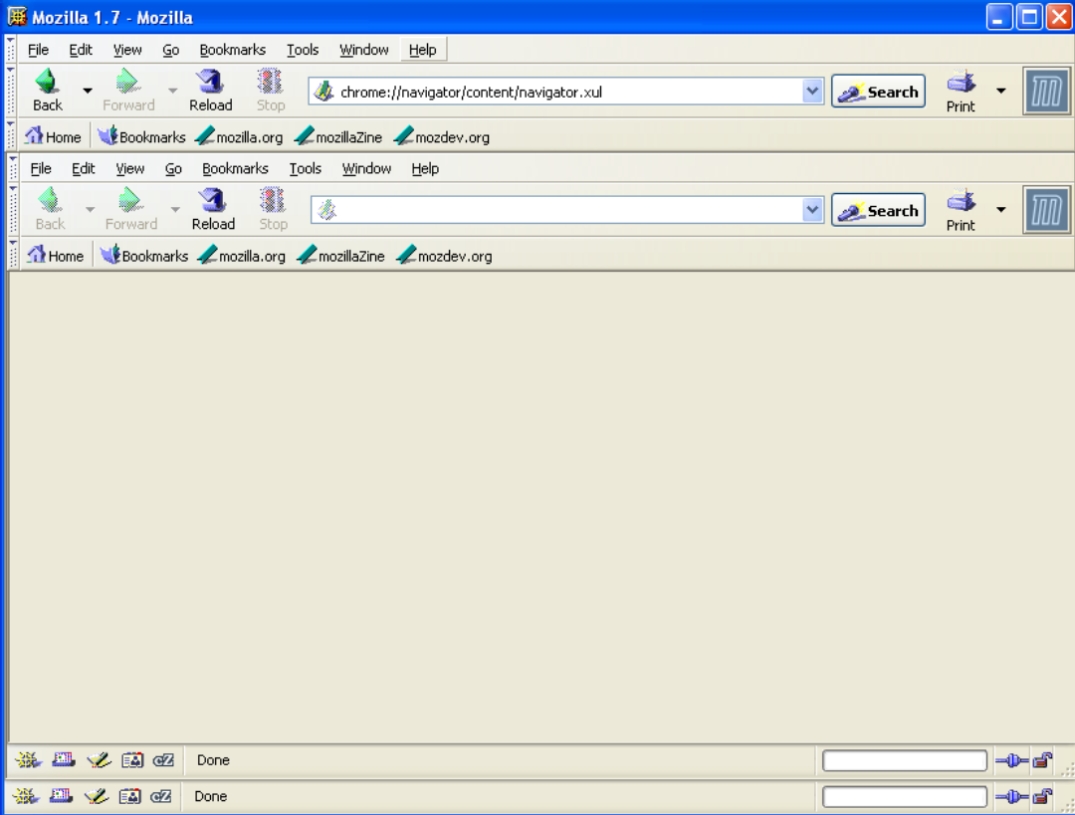

Thus, the Mozilla Navigator is a XUL document that can be loaded in the browser. In fact, if one tries to open the URL with Mozilla:

chrome://navigator/content

the result is quite amazing: an instance of a browser rendered inside another browser (figure 1).

Multithreading

Another interesting characteristic of Java is the support to concurrent programming. As Java programs are executed in a virtual machine, multi-programming is in theory possible even in those systems where multi-tasking and multi-threading is not supported by the kernel. In practice, today’s operating systems are all provided with a kernel able to schedule multiple threads and multiple processes. Another remarkable feature is that Java provides a single API for all platforms and thus a single construct for the concurrent programming which makes use of the object primitive functions wait, notify, and of the keyword synchronized. This construct is available from Java 1.0 to Java 1.4 and can be considered as a simplified form of the “monitor” construct. The model for concurrent programming has been improved since Java 1.5 to address some issues that are explained in [11].

Also Mozilla allows concurrent programming, but only by writing C/C++ code can you exploit the multi-threading API. In fact, an application written exclusively using XUL and Javascript is executed in a single threaded running environment, thus a blocking operation performed by our code cause the GUI to block. Javascript provides alternative tools like timers which are pieces of code executed at a given time with a given period, but in my opinion these are not as expressive as monitors and synchronized code in Java.

Portability

Portability is one of the key factors in both platforms. Java ensures the portability of the bytecode because the JVM provides a layer which isolates the code from the underlying machine. On the other hand, Mozilla applications are not homogeneous: they can contain XUL, Javascript, HTML, CSS, C/C++. The main issue is about the portability of C/C++ components. While binary portability is not ensured Mozilla, nevertheless, provides an API called Netscape Portable Runtime, which builds an abstraction layer between the C/C++ code and the underlying machine. Using this layer, the source code can be easily compiled in different operating systems.

Portability is an important value but it prevents the full exploitation of the underlying system, as code is portable only if it exploits those physical features which are common to all platforms. This is also a problem in mobile computing where Java provided API for Bluetooth and “mobile messaging” only when these features became “common” to many devices, causing the release of Java applications to be late in comparison with their C/C++ counterparts. The limited integration with the hosting system also affects the full exploitation of Desktop Managers like Windows and Gnome/KDE.

Portability is an important value but it prevents the full exploitation of the underlying system, as code is only portable if it exploits those physical features which are common to all platforms

Java API and XPCOM

Both platforms provide a rich set of API. The Java Development Kit provides the following categories of functionalities:

- GUI

- Images

- Input/Output on file/network/device

- Language Reflection

- Multithreading

- Network Datagram, Socket and ServerSocket

- Remote Method Interface

- Security

- Text manipulation

- Sound

- XML parsing

- Abstract database connections

On the other hand Mozilla provides a language neutral API. Components can be written and accessed in different languages while interfaces are defined with a common Interface Description Language called XPIDL (see figure 2).

The XPCOM API provides the following categories of functionality:

- Access to web platform components like address book, bookmarks, etc

- Multithreading

- Collections, Sets, Dictionaries

- LDAP

- Network

- RDF and XML

- SOAP, XML-RPC and WSDL.

SOAP and web services are directly supported in the Mozilla API, while in Java Standard Edition they can be used loading some additional libraries, or are alternatively bundled with the J2EE. On the other hand, Java provides the Remote Method Interface (RMI) which allows the building of distributed systems with object mobility and remote classloading.

Development tools

The luxuriant choice of tools for Java is probably the reason why Java programmers don’t migrate to other development platforms

The luxuriant choice of tools for Java is probably the reason why Java programmers don’t migrate to other development platforms.

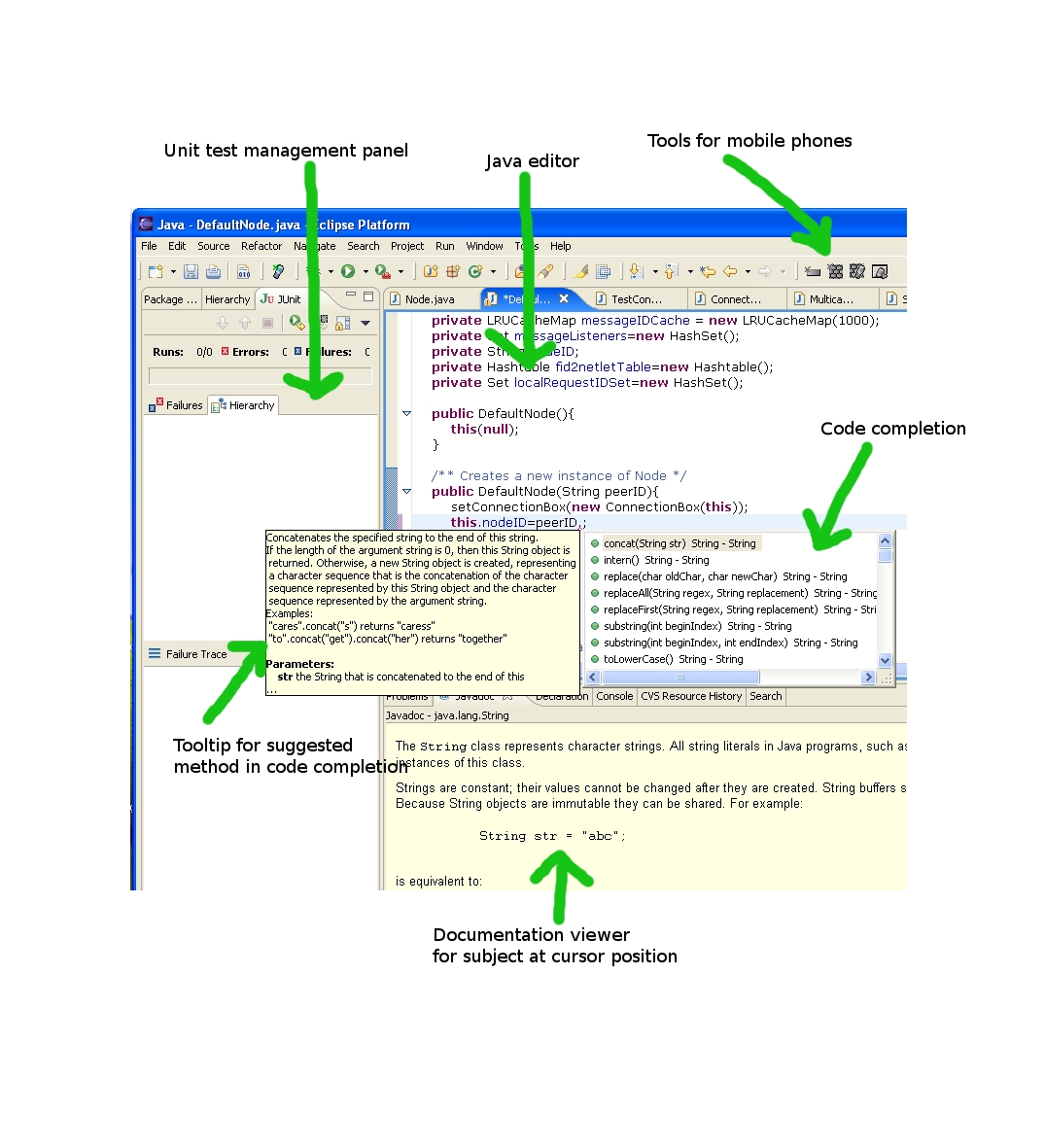

The quantity and quality of tools is impressive: code completion, refactoring tools, automatic generation of code portions, hyperlinking in source files, GUI visual editors, debuggers, test suites, build management, and automatic documentation. Moreover, integrated environments such as IntelliJ Idea, Eclipse, and others provide a single access point to all of the mentioned tools (figure 3) with quick access to CVS repositories.

So, the first problem for a Java programmer willing to experiment coding with Mozilla tools is “where is the IDE?”. Probably the main obstacle in having an IDE for Mozilla is the very heterogeneous nature of its languages, but in my opinion the Mozilla Foundation should focus in this direction to attract more developers.

Although an IDE for Mozilla is still missing, there are some interesting tools. Among others there are:

xpcshell: xpcshell is a command-line Javascript shell. It allows the testing of simple Javascript code snippets and also to load and test any kind of XPCOM. Unfortunately, the running environment of the xpcshell is not the same as a script in a XUL document, thus scripts that are expected to run in a GUI cannot be tested in the xpcshell.

jsshell [12]: jsshell is an interesting service which runs as a socket server in the Mozilla browser. It allows a TCP client to connect to the browser and prompts for Javascript commands. Differently from xpcshell, jsshell has the browser as the environment and it is very useful for testing extensions.

venkman [13]: venkman is a debugger for Javascript. It is installed as a tool in Mozilla and it is widely considered the best debugger for Javascript code.

Conclusion

The following table summarizes the comparison:

| Mozilla | Java | |

| Desktop | Good | Good |

| Mobile | Poor | Excellent |

| Server | Absent | Good |

| Web | Excellent | Good |

| License | Excellent | Poor |

| Community | Good | Good |

| Tools | Good | Excellent |

| Documentation | Good | Excellent |

| Portability | Good | Good |

| Multithreading | Poor | Good |

Comparison between Java and Mozilla

Assigning the scores: 0 to Absent, 1 to Poor, 2 to Good, 3 to Excellent, Java beats Mozilla 22 - 18. Nevertheless, the choice depends on the features you consider “really important” for your application.

Java is a language and on its platform you can build complete systems using Java for mobile client, desktop client, and server side components. Certainly, this is great for programmers, who can use a single development environment to code, test, debug, and deploy their application with an impressive productivity. Nevertheless, one characteristic of the internet is the “heterogeneity” and even if Java provides code mobility, this feature seems to have gained scarce popularity in the internet and it is limited in some niche of market and academia. So the Java bytecode has not become the lingua-franca; instead this role is probably assigned to XML.

Mozilla is open to inter-operability and is a language neutral platform as components can be written in any language (but to be honest they are consistently written in C++ and Javascript). Mozilla applications are often the integration of elements written in XUL, Javascript, RDF, HTML, CSS, and C++.

Maybe, the right question is “when should a programmer use Mozilla instead of Java?”. The ability to handle web content, GUIs, and multi-media inside Gecko is of course very interesting. Attempts to build an HTML layout engine in Java have never yielded good results (Sun HotJava has been discontinued, also the Netscape attempt to port the Navigator in Java failed. Currently, there is the Jazilla project which has the objective to build a Java version of Mozilla, but at the moment the result is quite poor).

As a last resort, it is possible to integrate Java and Mozilla: either embedding Gecko in a Java application or embedding Java applets in XUL documents. There is an on going project called blackconnect [14] which aims at the development of XPCOM in Java, but at the moment the project doesn’t seem very active.

In perspective, the internet is evolving from a web of documents to a web of services and the traditional HTML will become just one of the many ways to access the net. In any case Mozilla is ready to provide rich user interfaces for a satisfactory interaction with web services.

Bibliography

1(http://java.sun.com)/ Last visited 10/04/2005

[2] Tim O’Reilly. Mozilla.org Unleashes Mozilla 1.0 Last visited 15/04/2005

[3] Ina Fried and Paul Festa. Reversal: Next IE divorced from new Windows February 15, 2005.

4(http://www.ondotnet.com/pub/a/dotnet/2004/01/19/longhorn.html) Last visited 15/04/2005.

5(http://mab.mozdev.org) Last visited 15/04/2005.

6(http://games.mozdev.org/) Last visited 15/04/2005.

[7] Eric Raymond. Let Java go: an open letter to Scott McNealy, CEO of Sun Last visited 15/04/2005.

[8] Richard P. Gabriel and William N. Joy. Sun Community Source License Principles Last visited 15/04/2005.

[9] Jim Hamerly and Tom Paquin and Susan Walton. “Freeing the Source: The Story of Mozilla Open Sources”. Published in “Voices from the Open Source Revolution”. O’Reilly. ISBN 1-56592-582-3.

10(http://www.mozilla.org/why/framework-details.html) Last visited 15/04/2005.

[11] Qusay H. Mahmoud. Concurrent programming with J2SE 5.0 Last visited 15/04/2005.

12(http://www.croczilla.com/jssh) Last visited 15/04/2005.

13(http://www.hacksrus.com/~ginda/venkman/) Last visited 15/04/2005.

14(http://java.mozdev.org/blackconnect/) Last visited 15/04/2005.