In Chapter 1, I gave a brief overview of the Autotools and some of the resources that are currently available to help reduce the learning curve. In this chapter, we're going to step back a little and examine project organization techniques that are applicable to all projects, not just those whose build system is managed by the Autotools.

This chapter has downloads!

When you're done reading this chapter, you should be familiar with the common make targets, and why they exists. You should also have a solid understanding of why projects are organized the way they are. Trust me--by the time you finish this chapter, you'll already be well on your way to a solid understanding of the GNU Autotools.

The information provided by this chapter comes primarily from two sources:

In addition, you may find the GNU make manual very useful, if you'd like to brush up on your make syntax:

Creating a new project directory structure

There are two questions to ask yourself when setting up a new open source software (OSS) project build system:

- What platforms will I target?

- What do my users expect?

The first is an easy question to answer - you get to decide, but don't be too restrictive. Free software projects become great due to the number of people who've adopted them. Limiting the number of platforms arbitrarily is the direct equivalent of limiting the number of users. Now, why would you want to do that?!

The second question is more difficult, but not unsolvable. First, let's narrow the scope to something managable. We really mean to say, "What do my users expect of my build system?" A common approach for many OSS developers of determining these expectations is to download, unpack, build and install about a thousand different packages. You think I'm kidding? If you do this, eventually, you will come to know intuitively what your users expect of your build system. Unforutunately, package configuration, build and install processes vary so far from the "norm" that it's difficult to come to a solid conclusion about what the norm really is when using this technique.

A better way is to go directly to the source of the information. Like many developers new to the OSS world, I didn't even know there was a source of such information when I first started working on OSS projects. As it turns out, the source is quite obvious, after a little thought: The Free Software Foundation (FSF), better known as the GNU project. The FSF has published a document called The GNU Coding Standards, which covers a wide variety of topics related to writing, publishing and distributing free software--specifically for the FSF. Most non-GNU free software projects align themselves to one degree or another with the GNU Coding Standards. Why? Well...just because they were there first. And because their ideas make sense, for the most part.

Project structure

We'll start with a simple example project, and build on it as we continue our exploration of source-level software distribution. OSS projects generally have some sort of catchy name--often they're named after some past hero or ancient god, or even some made-up word--perhaps an acronym that can be pronounced like a real word. I'll call this the jupiter project, mainly because that way I don't have to come up with functionality that matches my project name! For jupiter, I'll create a project directory structure something like this:

$ cd projects

$ mkdir -p jupiter/src

$ touch jupiter/Makefile

$ touch jupiter/src/Makefile

$ touch jupiter/src/main.c

$ cd jupiter

$

Woot! One directory called src, one C source file called main.c, and a makefile for each of the two directories. Minimal yes, but hey, this is a new project, and everyone knows that the key to a successful OSS project is evolution, right? Start small and grow as needed (and, as you have time and inclination).

We'll start with support for the most basic of targets in any software project: all and clean. As we progress, it'll become clear that we need to add a few more important targets to this list, but for now, these will get us going. The top-level Makefile does very little at this point, merely passing requests for all and clean down to src/Makefile recursively. In fact, this is a fairly common type of build system, known as a recursive build system. Here are the contents of each of the three files in our project:

Makefile

all clean jupiter:

$(MAKE) -C src $@

src/Makefile

all: jupiter

jupiter: main.c

gcc -g -O0 -o $@ $+

clean:

-rm jupiter

src/main.c

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

int main(int argc, char * argv[])

{

printf("Hello from %s!\n", argv[0]);

return 0;

}

At this point, you may need to stop and take a refresher course in make syntax. If you're already pretty well versed on make, then you can skip the sidebar entitled, "Some makefile basics". Otherwise, give it a quick read, and then we'll continue building on this project.

Some makefile basics

For those like myself who use make only when they have to, it's often difficult to remember exactly what goes where in a makefile. Well, here are a few things to keep in mind. Besides comments, which begin with a HASH mark, there are only three types of entities in a makefile:

- variable assignments

- rules

- commands

NOTE: There are a half-dozen other types of constructs in a makefile, including conditional statements, directives, extension rules, pattern rules, function variables, include statements, etc. For the purposes of this chapter, we need not go into these constructs. This doesn't mean these other constructs are unimportant. On the contrary, they are very useful if you're going to write your own complex build system by hand. Our purpose here is to gain the background necessary for an understanding of the GNU Autotools, so I'll cover only that portion of make necessary to accomplish this goal. If you wish to have a much broader education on make syntax, please refer to the GNU make manual. Furthermore, if you wish to become a make expert, be prepared to spend a good deal of time on the project--there's much more to the make utility than is initially apparent on the surface.

Commands always start with a TAB character. Any line in a makefile beginning with a TAB character is ALWAYS considered by make to be a command. A list of one or more commands should always be associated with a preceeding rule.

NOTE: The fact that commands are required to be prefixed with an essentially invisible character is one of the most frustrating aspects of makefile syntax to both neophites and experts alike. The error messages generated by the legacy Unix make utility when a required TAB is missing, or when an unintentional TAB is inserted are obscure at best. As mentioned earlier, GNU make does a better job with such error messages these days. Nonetheless, be careful to use TAB characters properly in your makefiles--only before commands, which in turn immediately follow rules.

The general layout of a makefile is:

var1=val1

var2=val2

...

rule1

cmd1a

cmd1b

...

rule2

cmd2a

cmd2b

...

Variable assignments may take place at any point in the makefile, however you should be aware that make reads each makefile twice. The first pass gathers variables and rules into tables, and the second pass resolves dependencies defined by the rules. So regardless of where you put your variable definitions, make will act as though they'd all been declared at the top, in the order you specified them throughout the makefile.

Furthermore, make binds variable references to values at the very last minute--just before referencing commands are passed to the shell for execution. So, in general, variables may be assigned values by reference to other variables that haven't even been assigned yet. Thus, the order of variable assignment isn't really that important.

The make utility is a rule-based command engine. The rules indicate when and which commands should be executed. When you prefix a line with a TAB character, you're telling make that you want it to execute these statements from a shell according to the rules specified on the line above.

Of the remaining lines, those containing an EQUAL sign are variable definitions. Variables in makefiles are nearly identical to shell or environment variables. In Bourne shell syntax, you'd reference a variable in this manner: ${my_var}. In a makefile, the same syntax applies, except you would use parentheses instead of french braces: $(my_var). As in shell syntax, the delimiters are optional, but should be used to avoid ambiguous syntax when necessary. Thus, $my_var is functionally equivalent to $(my_var).

One caveat: If you ever want to use a shell variable inside a make command, you need to escape the DOLLAR sign by doubling it. For instance, $${shell_var}. This need arises occasionally, and it nearly always catches me off-guard the first time I use it in a new project.

Variables may be defined and used anywhere within a makefile. By default, make will read the entire process environment into the make variable table before processing the makefile. Thus, you can access any environment variables as if they were defined in the makefile itself. Note however, that variables set in the makefile will override those obtained from the environment. In general, it's a good idea not to depend on environment variables in your build process, although it's okay to use certain variables conditionally, if they're present. In addition, make defines several useful variables of its own, such as the MAKE variable, whose value is the file system path used to invoke the current make process.

Lines in my example makefiles that are not variable assignments (don't contain an EQUAL sign), and are not commands (are not prefixed with a TAB character), are all rules of one type or another. The rules used in my examples are known as "common" make rules, containing a single COLON character. The COLON character separates targets on the left from dependencies on the right. Targets are products--generally file system entities that can be produced by running one or more commands, such as a C compiler or a linker. Dependencies are source objects, or objects from which targets may be created. These may be computer language source files, or anything really that can be used by a command to generate a target object.

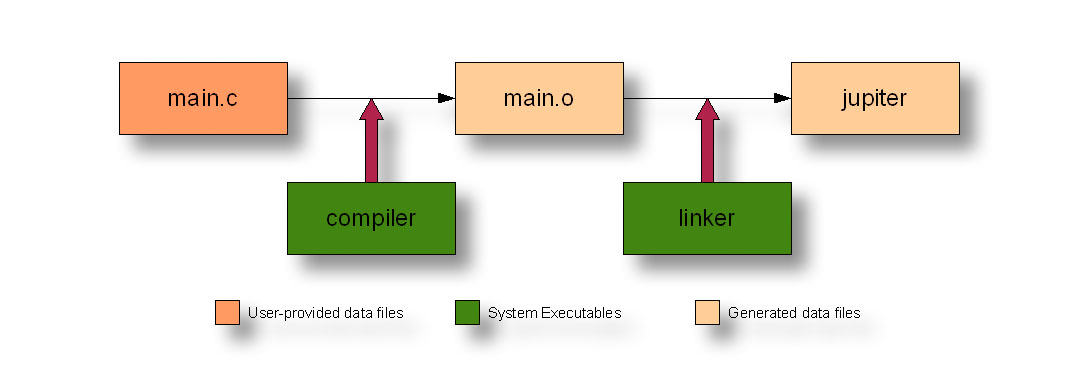

For example, a C compiler takes dependency main.c as input, and generates target main.o. A linker takes dependency main.o as input, and generates a named executable target, jupiter, in these examples:

The make utility implements some fairly complex logic to determine when a rule should be run based on whether the target exists or is older than its dependencies, but the syntax is trivial enough:

jupiter: main.o

ld main.o ... -o jupiter

main.o: main.c

gcc -c -g -O2 -o main.o main.c

This sample makefile contains two rules. The first says that jupiter depends on main.o, and the second says that main.o depends on main.c. Ultimately, of course, jupiter depends on main.c, but main.o is a necessary intermediate dependency in this case, because there are two steps to the process--compile and link--with an intermediate result in between. For each rule, there is an associated list of commands that make uses to build the target from the list of dependencies.

Of course, there is an easier way in the case of this example--gcc (as with most compilers) will call the linker for you--which, as you can probably tell from the elipsis in my example above, is very desirable. This alleviates the need for one of the rules, and provides a convenient way of adding more dependent files to the single remaining rule:

sources = main.c print.c display.c

jupiter: $(sources)

gcc -g -O2 -o jupiter $(sources)

NOTE: I should point out that using a single rule and command to process both steps is possible in this case because of the triviality of the example. In larger projects, skipping from source to executable in a single step is not possible. In these cases, using the compiler to call the linker can ease the burden in the second stage of determining all of the system objects that need to be linked into an application. And, in fact, this very technique is used quite often on Unix-like systems.

In this example, I've added a make variable to reduce redundancy. We now have a list of source files that is referenced in two places. But, it seems a shame to be required to reference this list twice in this manner, when the make utility knows which rule and which command it's dealing with at any moment during the process. Additionally, there may be other objects in the dependency list that are not in the sources variable. It would be nice to be able to reference the entire dependency list without duplicating that list.

As it happens, there are various "automatic" variables that can be used to reference portions of the controlling rule during the execution of a command. For example $(@) (or the more common syntax $@) references the current target, while $+ references the current list of dependencies:

sources = main.c print.c display.c

jupiter: $(sources)

gcc -g -O2 -o $@ $+

If you enter "make" on the command line, the make utility will look for the first target in a file named "Makefile" in the current directory, and try to build it using the rules defined in that file. If you specify a different target on the command line, make will attempt to build that target instead.

Targets need not be files only. They can also be so-called "phony targets", defined for convenience, as in the case of all and clean. These targets don't refer to true products in the file system, but rather to particular outcomes--the directory is "cleaned", or "all" desirable targets are built, etc.

In the same way that dependencies may be listed on the right side of the COLON, rules for multiple targets with the same dependencies may be combined by listing targets on the left side of the COLON, in this manner:

all clean jupiter:

$(MAKE) -C src $@

The -C command-line option tells make to change to the specified directory before looking for a makefile to run.

GNU Make is significantly more powerful than the original Unix make utility, although completely backward compatible, as long as GNU extensions are avoided. The GNU Make manual is available online. O'Reilly has an excellent book on the original Unix make utility and all of its many nuances. They also have a more recent book written specifically for GNU make that covers GNU Make extensions.

Creating a source distribution archive

It's great to be able to type "make all" or "make clean" from the command line to build and clean up this project. But in order to get the jupiter project source code to our users, we're going to have to create and distribute a source archive.

What better place to do this than from our build system. We could create a separate script to perform this task, and many people have done this in the past, but since we have the ability, through phony targets, to create arbitrary sets of functionality in make, and since we already have this general purpose build system anyway, we'll just let make do the work for us.

Building a source distribution archive is usually relegated to the dist target, so we'll add one. Normally, the rule of thumb is to take advantage of the recursive nature of the build system, by allowing each directory to manage its own portions of a global process. An example of this is how we passed control of building jupiter down to the src directory, where the jupiter source code is located. However, the process of building a compressed archive from a directory structure isn't really a recusive process--well, okay, yes it is, but the recursive portions of the process are tucked away inside the tar utility. This being the case, we'll just add the dist target to our top-level makefile:

Makefile

package = jupiter

version = 1.0

tarname = $(package)

distdir = $(tarname)-$(version)

all clean jupiter:

$(MAKE) -C src $@

dist: $(distdir).tar.gz

$(distdir).tar.gz: $(distdir)

tar chof - $(distdir) |\

gzip -9 -c >$(distdir).tar.gz

rm -rf $(distdir)

$(distdir):

mkdir -p $(distdir)/src

cp Makefile $(distdir)

cp src/Makefile $(distdir)/src

cp src/main.c $(distdir)/src

.PHONY: all clean dist

In this version of the top-level Makefile, we've added a new construct, the .PHONY rule. At least it seems like a rule--it contains a COLON character, anyway. The .PHONY rule is a special kind of rule called a "dot-rule", which is built into make. The make utility understands several different dot-rules. The purpose of the .PHONY rule is simply to tell make that certain targets don't generate file system objects, so make won't go looking for product files in the file system that are named after these targets. Normally, the make utility determines which commands to run by comparing the time stamps of the associated rule products to those of their dependencies in the file system, but phony targets don't have associated file system objects.

We've added the new dist target in the form of three rules for the sake of readability, modularity and maintenance. This is a great rule of thumb to following in any software engineering process: Build large processes from smaller ones, and reuse the smaller processes where it makes sense to do so.

The dist target depends on the existance of the ultimate goal, a source-level compressed archive package, jupiter-1.0.tar.gz--also known as a "tarball". I've added a make variable for the version number to ease the process of updating the project version later, and I've used another variable for the package name for the sake of possibly porting this makefile to another project. I've also logically split the functions of package name and tar name, in case we want them to be different later--the default tar name is the package name. Finally, I've combined references to these variables into a distdir variable to reduce duplication and complexity in the makefile.

The rule that builds the tarball indicates how this should be done with a command that uses the gzip and tar utilities to create the file. But, notice also that the rule has a dependency--the directory to be archived. We don't want everything in our project directory hierarchy to go into our tarball--only exactly those files that are necessary for the distribution. Basically, this means any file required to build and install our project. We certainly don't want object files and executables from our last build attempt to end up in the archive, so we have to build a directory containing exactly what we want to ship. This pretty much mandates the use of individual cp commands, unfortunately.

Since there's a rule in the makefile that tells how this directory should be created, make runs the commands for this rule before running the commands for the current rule. The make utility runs rules to build dependencies recursively until the requested target's commands can be run.

Forcing a rule to run

There's a subtle flaw in the $(distdir) target that may not be obvious, but it will rear its ugly head at the worst times. If the archive directory already exists when you type make dist, then make won't try to create it. Try this:

$ mkdir jupiter-1.0

$ make dist

tar chof - jupiter-1.0 | gzip -9 -c >jupiter-1.0...

rm -rf jupiter-1.0 &> /dev/null

$

Notice that the dist target didn't copy any files--it just built an archive out of the existing jupiter-1.0 directory, which was empty. Our end-users would have gotten a real surpise when they unpacked this tarball!

The problem is that the $(distdir) target is a real target with no dependencies, which means that make will consider it up-to-date as long as it exists in the file system. We could add $(distdir) to the .PHONY rule, but this would be a lie--it's not a phony target, it's just that we want to force it to be rebuilt every time.

The proper way to ensure it gets rebuilt is to have it not exist before make attempts to build it. A common method for accomplishing this task to to create a true phony target that will run every time, and add it to the dependency chain at or above the $(distdir) target. For obvious reasons, a commonly used name for this sort of target is "FORCE":

Makefile

...

$(distdir).tar.gz: FORCE $(distdir)

tar chof - $(distdir) |\

gzip -9 -c >$(distdir).tar.gz

rm -rf $(distdir)

$(distdir):

mkdir -p $(distdir)/src

cp Makefile $(distdir)

cp src/Makefile $(distdir)/src

cp src/main.c $(distdir)/src

FORCE:

-rm $(distdir).tar.gz &> /dev/null

-rm -rf $(distdir) &> /dev/null

.PHONY: FORCE all clean dist

The FORCE rule's commands are executed every time because FORCE is a phony target. By making FORCE a dependency of the tarball, we're given the opportunity to delete any previously created files and directories before make begins to evaluate whether or not these targets' commands should be executed. This is really much cleaner, because we can now remove the "pre-cleanup" commands from all of the rules, except for FORCE, where they really belong.

There are actually more accurate ways of doing this--we could make the $(distdir) target dependent on all of the files in the archive directory. If any of these files are newer than the directory, the target would be executed. This scheme would require an elaborate shell script containing sed commands or non-portable GNU make functions to replace file paths in the dependency list for the copy commands. For our purposes, this implementation is adequate. Perhaps it would be worth the effort if our project were huge, and creating an archive directory required copying and/or generating thousands of files.

The use of a leading DASH character on some of the rm commands is interesting. A leading DASH character tells make to not care about the status code of the associated command. Normally make will stop execution with an error message on the first command that returns a non-zero status code to the shell. I use a leading DASH character on the rm commands in the FORCE rule because I want to delete previously created product files that may or may not exist, and rm will return an error if I attempt to delete a non-existent file. Note that I explicitly did NOT use a leading DASH on the rm command in the $(distdir) rule. This is because this rm command must succeed, or something is very wrong, as the preceeding command should have created a tarball from this directory.

Another such leading character that you may encounter is the ATSIGN (@) character. A command prefixed with an ATSIGN tells make not to print the command as it executes it. Normally make will print each command as it's executed. A leading ATSIGN tells make that you don't want to see this command. This is a common thing to do on echo statements--you don't want make to print echo statements, because then your message will be printed twice, and that's just ugly.

Automatically testing a distribution

The rule for building the archive directory is the most frustrating of any in this makefile--it contains commands to copy files individually into the distribution directory. What a sad shame! Everytime we change the file structure in our project, we have to update this rule in our top-level makefile, or we'll break our dist target.

But, there's nothing to be done for it. We've made the rule as simple as possible. Now, we just have to remember to manage this process properly. But unfortunately, breaking the dist target is not the worst thing that could happen if we forget to update the distdir rule's commands. The dist target may continue to appear to work, but not actually copy all of the required files into the tarball. This will cause us some embarassment when our users begin to send us emails asking why our tarball doesn't build on their systems.

In fact, this is a far more common possibility than that of breaking the dist target, because the more common activity while working on a project is to add files to the project, not move them around or delete them. New files will not be copied, but the dist rule won't notice the difference.

If only there were some way of unit-testing this process. As it turns out, there is a way of performing a sort of self-check on the dist target. We can create yet another phony target called "distcheck" that does exactly what our users will do--unpack the tarball, and build the project. We can do this in a new temporary directory. If the build process fails, then the distcheck target will break, telling us that we forgot something crucial in our distribution.

Makefile

...

distcheck: $(distdir).tar.gz

gzip -cd $+ | tar xvf -

$(MAKE) -C $(distdir) all clean

rm -rf $(distdir)

@echo "*** Package $(distdir).tar.gz\

ready for distribution."

...

.PHONY: FORCE all clean dist distcheck

Here, we've added the distcheck target to the top-level makefile. Since the distcheck target depends on the tarball itself, it will first build a tarball using the same targets used by the dist target. It will then execute the distcheck commands, which are to unpack the tarball it just built and run "make all clean" on the resulting directory. This will build both the all and clean targets, successively. If that process succeeds, it will print out a message, telling us that we can sleep well knowing that our users will probably not have a problem with this tarball.

Now all we have to do is remember to run "make distcheck" before we post our tarballs for public distribution!

Unit testing anyone?

Some people think unit testing is evil, but really--the only honest rationale they can come up with for not doing it is laziness. Let's face it--proper unit testing is hard work, but it pays off in the end. Those who do it have learned a lesson (usually as children) about the value of delayed gratification.

A good build system is no exception. It should encorporate proper unit testing. The commonly used target for testing a build is the check target, so we'll go ahead and add the check target in the usual manner. The test should probably go in src/Makefile because jupiter is built in src/Makefile, so we'll have to pass the check target down from the top-level makefile.

But what commands do we put in the check rule? Well, jupiter is a pretty simple program--it prints out a message, "Hello from grep utility to test our assertion:

Makefile

...

all clean check jupiter:

$(MAKE) -C src $@

...

.PHONY: FORCE all clean check dist distcheck

src/Makefile

...

check: all

./jupiter | grep "Hello from .*jupiter!"

@echo "*** ALL TESTS PASSED ***"

...

.PHONY: all clean check

Note that check is dependent on all. We can't really test our products unless they've been built. We can ensure they're up to date by creating such a dependency. Now make will run commands for all if it needs to before running the commands for check.

There's one more thing we could do to enhance our build system a bit. We can add the check target to the make command in our distcheck target. Adding it right between the all and clean targets seems appropriate:

Makefile

...

distcheck: $(distdir).tar.gz

gzip -cd $+ | tar xvf -

$(MAKE) -C $(distdir) all check clean

rm -rf $(distdir)

@echo "*** Package $(distdir).tar.gz\

ready for distribution."

...

Now, when we run "make distcheck", our entire build system will be tested before packaging is considered successful. What more could you ask for?!

Installing products

Well, we've now reached the point where our users' experiences with our project should be fairly painless--even pleasant, as far as building the project is concerned. Our users will simply unpack the distribution tarball, change into the distribution directory, and type "make". It can't really get any simpler than that.

But still we lack one important feature--installation. In the case of the jupiter project, this is fairly trivial - there's only one executable, and most users could probably guess that this file should be copied into either the /usr/bin or /usr/local/bin directory. More complex projects, however could cause our users some real consternation when it comes to where to put user and system binaries, libraries, header files, and documentation, including man pages, info pages, pdf files, and README, INSTALL and COPYRIGHT files. Do we really want our users to have to figure all that out?

I don't think so. So we'll just create an install target that manages putting things where they go, once they're built properly. Why not just make installation part of the all target? A few reasons, really. First, build and installation are separate logical concepts. Remember the rule: Break up large processes into smaller ones and reuse the smaller ones where you can. The second reason is a matter of rights. Users have rights to build in their own home directories, but installation often requires root-level rights to copy files into system directories. Finally, there are several reasons why a user may wish to build, but not install.

While creating a distribution package may not be an inherently recursive process, installation certainly is, so we'll allow each subdirectory in our project to manage installation of its own components. To do this, we need to modify both makefiles. The top-level makefile is easy. Since there are no products to be installed in the top-level directory, we'll just pass on the responsibility to src/Makefile in the usual way:

Makefile

...

all clean check install jupiter:

$(MAKE) -C src $@

...

.PHONY: FORCE all clean check dist distcheck

.PHONY: install

src/Makefile

...

install:

cp jupiter /usr/bin

chown root:root /usr/bin/jupiter

chmod +x /usr/bin/jupiter

.PHONY: all clean check install

In the top-level makefile, we've added install to the list of targets passed down to src/Makefile. In both files we've added install to the phony target list.

As it turns out, installation was a bit more complex than simply copying files. If a file is placed in the /usr/bin directory, then the root user should own it so that only the root user can delete or modify it. Additionally, we should ensure that the jupiter binary is executable, so we use the chmod command to set the mode of the file to executable. This is probably redundant, as the linker ensures that jupiter gets created as an executable file, but it never hurts to be safe.

Now our users can just type the following sequence of commands, and have our project built and installed with the correct system attributes and ownership on their platforms:

$ tar -zxvf jupiter-1.0.tar.gz

$ cd jupiter-1.0

$ make all

$ sudo make install

All of this is well and good, but it could be a bit more flexible with regard to where things get installed. Some of our users may be okay with having jupiter installed into the /usr/bin directory. Others are going to ask us why we didn't put it into the /usr/local/bin directory--after all, this is a common convention. Well, we could change the target directory to /usr/local/bin, but then others will ask us why we didn't just put it into the /usr/bin directory. This is the perfect situation for a little command-line flexibility.

Another problem we have with these makefiles is the amount of stuff we have to do to install files. Most Unix systems provide a system-level program called "install", which allows a user to specify, in an intelligent manner, various attributes of the files being installed. The proper use of this utility could simplify things a bit. While we're adding location flexibility, I'll just go ahead and add the use of the install utility, as well:

Makefile

...

export prefix=/usr/local

all clean install jupiter:

$(MAKE) -C src $@

...

src/Makefile

...

install:

install -d $(prefix)/bin

install -m 0755 jupiter $(prefix)/bin

...

If you're astute, you may have noticed that I've declared and assigned the prefix variable in the top-level makefile, but I've referenced it in src/Makefile. This is possible because I used the export modifier in the top-level makefile to export this make variable to the shell that make spawns when it executes itself in the src directory. This is a nice feature of make because it allows us to define all of our user variables in one obvious location--at the top of the top-level makefile.

I've now declared the prefix variable to be /usr/local, which is very nice for those who want jupiter to be installed in /usr/local/bin, but not so nice for those who just want it installed in /usr/bin. Fortunately, make allows the definition of make variables on the command line, in this manner:

$ sudo make prefix=/usr install

...

Variables defined on the command line override those defined in the makefile. Thus, users who want to install jupiter into their /usr/bin directory now have the option of specifying this on the make command line when they install jupiter.

Actually, with this system in place, our users may install jupiter into any directory they choose, including a location in their home directory, for which they do not need additional rights granted. This is, in fact, the reason for the addition of the mkdir -p command. We don't actually know where the user is going to install jupiter now, so we have to be prepared for the possiblity that the location may not yet exist.

A bit of trivia about the install utility--it has the interesting property of changing the ownership of any file it copies to the owner and group of the containing directory. So it automatically sets the owner and group of our installed files to root:root if the user tries to use the default /usr/local prefix, or to the user's id and group if she tries to install into a location within her home directory. Nice, huh?

Uninstalling a package

What if a user doesn't like our package after it's been installed, and she just wants to get it off her system? This is fairly likely with the jupiter package, as it's rather useless and takes up valuable space in her bin directory. In the case of your projects however, it's more likely that she wants to install a newer version of your project cleanly, or she wants to change from the test build she downloaded from your website to a professionally packaged version of your project provided by her Linux distribution. We really should have an uninstall target, for these and other reasons:

Makefile

...

all clean install uninstall jupiter:

$(MAKE) -C src $@

...

.PHONY: FORCE all clean dist distcheck

.PHONY: install uninstall

src/Makefile

...

uninstall:

-rm $(prefix)/bin/jupiter

.PHONY: all clean check install uninstall

And, again, this particular target will require root-level rights if the user is using a system prefix, such as /usr or /usr/local. The list of things to maintain is getting a out of hand, if you ask me. We now have two places to update when changing our installation processes--the install and uninstall targets. Unfortunately, this is really about the best we can hope for when writing our own makefiles, without resorting to fairly complex shell script commands. Hang in there--in Chapter 6, I'll show you how this example can be rewritten in a much simpler way using Automake.

Finally, while we're at it, let's add testing the install and uninstall targets to our distcheck target:

Makefile

...

distcheck: $(distdir).tar.gz

gzip -cd $+ | tar xvf -

$(MAKE) -C $(distdir) all check

$(MAKE) -C $(distdir) prefix=\

$${PWD}/$(distdir)/_inst install uninstall

$(MAKE) -C $(distdir) clean

rm -rf $(distdir)

@echo "*** Package $(distdir).tar.gz\

ready for distribution."

...

To do this properly, I had to break up the $(MAKE) commands into three different steps, so that we could add the proper prefix to the install and uninstall targets without affecting the other targets. I'll have more to say on this topic in a few minutes.

Note also that I used a double DOLLAR sign on the $${PWD} variable reference. This was done in order to ensure that make passed the reference to the shell with the rest of the command line. I wanted this variable to be dereferenced by the shell, rather than the make utility. Technically, I didn't have to do this because the PWD variable was initialized for make from the environment, but it serves as a good example of this process.

The Filesystem Hierarchy Standard

By the way, where am I getting these directory names from? What if some Unix system out there doesn't use /usr or /usr/local? Well, in the first place, this is another reason for providing the prefix variable--to handle those sorts of situations. However, most Unix and Unix-like systems nowadays follow the Filesystem Hierarchy Standard (FHS), as closely as possible. The FHS defines a number of "standard places", including the following root-level directories:

/bin/etc/home/opt/sbin/srv/tmp/usr/var

This list is not exhaustive. I've only mentioned the ones most relevant to our purposes. In addition, the FHS defines several standard locations beneath these root-level directories. For instance, the /usr directory should contain the following sub-directories:

/usr/bin/usr/include/usr/lib/usr/local/usr/sbin/usr/share/usr/src

The /usr/local directory should contain a structure very similar to the /usr directory structure, so that if the /usr/bin directory (for instance) is an NFS mount, then /usr/local/bin (which should always be local) may contain local copies of some programs. This way, if the network is down, the system may still be usable, to some degree.

Not only does the FHS define these standard locations, but it also explains in fair detail what they are for, and what types of files should be kept there. All in all, the FHS leaves just enough flexibility and choice to you as a project maintainer to keep your life interesting, but not enough to make you lose sleep at night, wondering if you're installing your files in the right places.

Before I found out about the FHS, I relied on my personal experience to decide where files should be installed in my projects. Mostly I was right, because I'm a careful guy, but I have gone back to some of my past projects with a bit of chagrin and changed things, once I read the FHS document. I heartily recommend you become thoroughly familiar with this document if you seriously intend to develop Unix software.

Supporting standard targets and variables

In addition to those I've already mentioned, the GNU Coding Standards document lists some important targets and variables that you should support in your projects, mainly because everyone else does and your users will expect them.

Some of the chapters in the GNU Coding Standards should be taken with a grain of salt (unless you're actually working on a GNU sponsored project, in which case you're probably not reading this book because you need to). For example, you probably won't care much about the C source code formatting suggestions in Chapter 5. Your users certainly won't care, so you can use whatever source code formatting style you wish.

That's not to say that all of Chapter 5 is worthless. Sections 5.5 and 5.6, for instance, provide excellent information on C source code portability between POSIX-oriented platforms and CPU types. Section 5.8 gives some tips on using GNU software to internationalize your program. This is excellent material.

While Chapter 6 discusses documentation the GNU way, some sections of Chapter 6 describe various top-level text files found commonly in projects, such as the AUTHORS, NEWS, INSTALL, README and ChangeLog files. These are all bits that the well-read OSS user expects to see in any decent OSS project.

But, the really useful information in the GNU Coding Standards document begins in Chapter 7, "The Release Process". The reason why this chapter is so critical to you as an OSS project maintainer, is that it pretty much defines what your users will expect of your project's build system. Chapter 7 is the defacto-standard for user options provided by packages using source-level distribution.

Section 7.1 defines the configuration process, about which we haven't spent much time so far in this chapter, but we'll get to it. Section 7.2 covers makefile conventions, including all of the "standard targets" and "standard variables" that users have come to expect in OSS packages. Standard targets defined by the GNU Coding Standards document include:

allinstallinstall-htmlinstall-dviinstall-pdfinstall-psuninstallinstall-stripcleandistcleanmostlycleanmaintainer-cleanTAGSinfodvihtmlpdfpsdistcheckinstallcheckinstalldirs

Note that you don't need to support all of these targets, but you should consider supporting those which make sense for your project. For example, if you build and install HTML pages in your project, then you should probably consider supporting the html and install-html targets. Autotools projects support these, and more. Some of these are useful to users, while others are only useful to maintainers.

Variables that your project should support (as you see fit) include the following. I've added the default values for these variables on the right. You'll note that most of these variables are defined in terms of a few of them, and ultimately only one of them, prefix. The reason for this is (again) flexibility to the end user. I call these "prefix variables", for lack of a more standard name:

prefix = /usr/local

exec-prefix = $(prefix)

bindir = $(exec_prefix)/bin

sbindir = $(exec_prefix)/sbin

libexecdir = $(exec_prefix)/libexec

datarootdir = $(prefix)/share

datadir = $(datarootdir)

sysconfdir = $(prefix)/etc

sharedstatedir = $(prefix)/com

localstatedir = $(prefix)/var

includedir = $(prefix)/include

oldincludedir = /usr/include

docdir = $(datarootdir)/doc/$(package)

infodir = $(datarootdir)/info

htmldir = $(docdir)

dvidir = $(docdir)

pdfdir = $(docdir)

psdir = $(docdir)

libdir = $(exec_prefix)/lib

lispdir = $(datarootdir)/emacs/site-lisp

localedir = $(datarootdir)/locale

mandir = $(datarootdir)/man

manNdir = $(mandir)/manN (N = 1..9)

manext = .1

manNext = .N (N = 1..9)

srcdir = (compiled project root)

Autotools projects support these and other useful variables automatically. Projects that use Automake get these variables for free. Autoconf provides a mid-level form of support for these variables. If you write your own makefiles and build system, you should support as many of these as you use in your build and install processes.

To support the variables and targets that we've used so far in the jupiter project, we need to add the bindir variable, in this manner:

Makefile

...

export prefix = /usr/local

export exec_prefix = $(prefix)

export bindir = $(exec_prefix)/bin

...

src/Makefile

...

install:

install -d $(bindir)

install -m 0755 jupiter $(bindir)

uninstall:

-rm $(bindir)/jupiter

...

Note that we have to export prefix, exec_prefix and bindir, even though we only use bindir explicitly in src/Makefile. The reason for this is that bindir is defined in terms of exec_prefix, which is itself defined in terms of prefix. So when make runs the install command, it will first resolve bindir to $(exec_prefix)/bin, and then to $(prefix)/bin, and finally to /usr/local/bin--src/Makefile obviously needs access to all three variables during this process.

How do such recursive variable definitions make life better for the end-user? The user can change the root install location from /usr/local to /usr by simply typing:

$ make prefix=/usr install

...

The ability to change these variables like this is particularly useful to a Linux distribution packager, who needs to install packages into very specific system locations:

$ make prefix=/usr sysconfdir=/etc install

...

Getting your project into a Linux distro

The dream of every OSS maintainer is that his or her project will be picked up by a Linux distribution. When a Linux "distro" picks up your package for distribution on their CD's and DVD's, your project will be moved magically from the realm of tens of users to that of tens of thousands of users--almost overnight.

By following the GNU Coding Standards with your build system, you remove many barriers to including your project in a Linux distro, because distro packagers (employees of the company, whose job it is to professionally package your project as RPM or APT packages) will immediately know what to do with your tarball, if it follows all the usual conventions. And, in general, packagers get to decide, based on needed functionality, and their feelings about your package, whether or not it should be included in their flavor of Linux.

Section 7.2.4 of the GNU Coding Standards talks about the concept of supporting "staged installations". This is a concept easily supported by a build system, but which if neglected, will almost always cause problems for Linux distro packagers.

Packaging systems such as the Redhat Package Manager (RPM) system accept one or more tarballs, a set of patches and a specification file (in the case of RPM, called an "rpm spec file"). The spec file describes the process of building and installing your package. In addition, it defines all of the products installed into the targeted installation directory hierarchy. The package manager software uses this information to install your package into a temporary directory, from which it pulls the specified binaries, storing them in a special binary archive that the package installation software (eg., rpm) understands.

To support staged installation, all you really need to do is provide a variable named "DESTDIR" in your build system that is a sort of super-prefix to all of your installed products. To show you how this is done, I'll add staged installation support to the jupiter project. This is so trivial, it only requires three changes to src/Makefile:

src/Makefile

...

install:

install -d $(DESTDIR)$(bindir)

install -m 0755 jupiter $(DESTDIR)$(bindir)

uninstall:

-rm $(DESTDIR)$(bindir)/jupiter

...

As you can see, I've added the $(DESTDIR) prefix to the $(bindir) references in our install and uninstall targets that reference any installation paths. I didn't need to add $(DESTDIR) to the uninstall command for the sake of package managers, because they don't care how your package is uninstalled. Package managers only install your package while building it so they can copy the specified products from the temporary install directory, which they then delete entirely after the package is created. Package managers like RPM use their own rules for removing products from a system, and these rules are based on package manager databases, not your build system.

For the sake of symmetry and to be complete, it doesn't hurt to add $(DESTDIR) to uninstall. Besides, we need it to be complete for the sake of the distcheck target, which we'll now modify to take advantage of our staged installation functionality:

Makefile

...

distcheck: $(distdir).tar.gz

gzip -cd $+ | tar xvf -

$(MAKE) -C $(distdir) all check

$(MAKE) -C $(distdir) DESTDIR=\

$${PWD}/$(distdir)/_inst install uninstall

$(MAKE) -C $(distdir) clean

rm -rf $(distdir)

@echo "*** Package $(distdir).tar.gz\

ready for distribution."

...

Changing the prefix variable to the DESTDIR variable in the second $(MAKE) line above allows us to test a complete install directory hierarchy properly, as we'll see shortly here.

At this point, an RPM spec file (for example) could provide the following text as the installation commands for the jupiter package:

%install

make prefix=/usr DESTDIR=%BUILDROOT install

But don't worry about package manager file formats. Just focus on providing staged installation functionality through the DESTDIR variable.

You may be wondering why this functionality could not be provided by the prefix variable. Well, for one thing, not every path in a system-level installation is defined relative to the prefix variable. The system configuration directory (sysconfdir), for instance, is often defined simply as /etc by packagers. Defining prefix to anything other than / will have little effect on sysconfdir during staged installation, unless a build system uses $(DESTDIR)$(sysconfdir) to reference the system configuration directory. Other reasons for this will become more clear as we talk about project configuration later in this chapter.

Build versus installation prefix overrides

At this point, I'd like to digress slightly for just a moment to explain an elusive (or at least non-obvious) concept regarding the prefix and other path variables defined by the GNU Coding Standards document.

In the preceeding examples, I've always used prefix overrides on the make install command line, like this:

$ make prefix=/usr install

...

The question I wish to address is: What's the difference between using a prefix override for make all and make install? In our small sample makefiles, we've managed to avoid using prefixes in any targets not related to installation, so it may not be clear at this point that a prefix is ever useful during the build stages.

One key use of prefix variables during the build stage is to substitute paths into source code at compile time, in this manner:

main.o : main.c

gcc -DCFGDIR=\"$(sysconfdir)\" -o $@ $+

In this example, I'm defining a C preprocessor variable called CFGDIR on the compiler command line for use by main.c. Presumably, there's some code in main.c that looks like this:

#ifndef CFGDIR

# define CFGDIR "/etc"

#endif

char cfgdir[FILENAME_MAX] = CFGDIR;

Later in the code, the C global variable "cfgdir" might be used to access the application's configuration file.

Okay, with that background then, would you ever want to use different prefix variable overrides on the build and installation command lines? Sure--Linux distro packagers do this all the time in RPM spec files. During the build stage, the actual run-time directories are hard-coded into the executable by using a command like this:

%build

%setup

./configure prefix=/usr sysconfdir=/etc

make

The RPM build process installs these executables into a stage directory, so it can copy them out. The corresponding installation command looks like this:

%install

rm -rf %BUILDROOT%

make DESTDIR=%BUILDROOT% install

I mentioned the DESTDIR variable previously as a tool used by packagers for staged installation. This has the same effect as using:

%install

rm -rf %BUILDROOT%

make prefix=%BUILDROOT%/usr \

sysconfdir=%BUILDROOT%/etc install

The key take-away point here is this: Never recompile from an install target in your makefiles. Otherwise your users won't be able to access your staged installation features when using prefix overrides.

Another reason for this is to allow the user to install into a grouped location, and then create links to the actual files in the proper locations. Some people like to do this, especially when they are testing out a package, and want to keep track of all of its components. For example, some Linux distributions provide a way of installing multiple versions of some common packages. Java is a great example here. To support using multiple versions or brands (perhaps Sun Java vs IBM Java), the Linux distribution provides a script set called the "alternatives" scripts, which allows a user (running as root) to swap all of the links in the various system directories from one grouped installation to another. Thus, both sets of files may be installed in different auxiliary locations, but links in the true installation locations can be changed to refer to each group at different times.

One final point about this issue. If you're installing into a system directory hierarchy, you'll need root permissions. Often people run make install like this:

$ sudo make install

...

If your install target depends on your build targets, and you've neglected to build beforehand, then make will happily build your program before installing it, but the local copies will all be owned by root. Just an inconvenience, but easily avoided by having `make install' fail for lack of things to install, rather than simply jump right into a build while running as root.

Standard user variables

There's one more topic I'd like to cover before we move on to configuration. The GNU Coding Standards document defines a set of variables that are sort of sacred to the user. That is, these variables should be used by a GNU build system, but never modified by a GNU build system. These are called "user variables", and they include the following for C and C++ programs:

CC - the C compiler

CFLAGS - C compiler flags

CXX - the C++ compiler

CXXFLAGS - C++ compiler flags

LDFLAGS - linker flags

CPPFLAGS - C preprocessor flags

...

This list is by no means comprehensive, and ironically, there isn't a comprehensive list to be found in the GCS document. Interestingly, most of these user variables come from the documentation for the make utility. You can find a fairly complete list of program name and flag variables in section 10.3 of the GNU make manual. The reason for this is that these variables are used in the built-in rules of the make utility.

For our purposes, these few are sufficient, but for a more complex makefile, you should become familiar with the larger list so that you can use them as the occasion arises. To use these in our makefiles, we'll just replace "gcc" with $(CC), and then set CC to the gcc compiler at the top of the makefile. We'll do the same for CFLAGS and CPPFLAGS, although this last one will contain nothing by default:

src/Makefile

...

CC = gcc

CFLAGS = -g -O2

...

jupiter: main.c

$(CC) $(CFLAGS) $(CPPFLAGS) -o $@ $+

...

The reason this works is that the make utility allows such variables to be overridden by options on the command line. Make command-line variable assignments always override values set in the makefiles themselves. Thus, to change the compiler and set some compiler flags, a user need simply type:

$ make CC=gcc3 CFLAGS='-g -O0' CPPFLAGS=-dtest

In this case, our user has decided to use gcc version 3 instead of 4, and to disable optimization and leave the debugging symbols in place. She's also decided to enable the "test" option through the use of a preprocessor definition. Note that these variables are set on the make command line. This apparently equivalent syntax will not work as expected:

$ CC=gcc3 CFLAGS='-g -O0' CPPFLAGS=-dtest make

The reason for this is that we're merely setting environment variables in the local environment passed to the make utility by the shell. Remember that environment variables do not automatically override those set in the makefile. To get the functionality we want, we could use a little GNU make-specific syntax in our makefile:

CC ?= gcc

CFLAGS ?= -g -O2

The "?=" operation is a GNU Make-specific operator, which will only set the variable in the makefile if it hasn't already been set elsewhere. This means we can now override these particular variable settings by setting them in the environment. But don't forget that this will only work in GNU Make.

Configuring your package

The GNU Coding Standards document describes the configuration process in section 7.1, "How Configuration Should Work". Up to this point, we've been able to do about everything we've wanted to do with the jupiter project using only makefiles. You might be wondering at this point what configuration is actually for! The opening paragraphs of Section 7.1 state:

Each GNU distribution should come with a shell script named

configure. This script is given arguments which describe the kind of machine and system you want to compile the program for.The

configurescript must record the configuration options so that they affect compilation.One way to do this is to make a link from a standard name such as

config.hto the proper configuration file for the chosen system. If you use this technique, the distribution should not contain a file namedconfig.h. This is so that people won't be able to build the program without configuring it first.Another thing that

configurecan do is to edit the makefiles. If you do this, the distribution should not contain a file namedMakefile. Instead, it should include a fileMakefile.inwhich contains the input used for editing. Once again, this is so that people won't be able to build the program without configuring it first.

So then, the primary tasks of a typical configure script are to:

- generate files from templates containing replacement variables,

- generate a C language header file (often called

config.h) for inclusion by project source code, - set user options for a particular

makeenvironment--such as debug flags, etc., - set various package options as environment variables,

- and test for the existance of tools, libraries, and header files.

For complex projects, configure scripts often generate the project makefile(s) from one or more templates maintained by project developers. A makefile template contains configuration variables in an easily recognized (and substituted) format. The configure script replaces these variables with values determined during configuration--either from command line options specified by the user, or from a thorough analysis of the platform environment. Often this analysis entails such things as checking for the existence of certain system or package include files and libraries, searching various file system paths for required utilities and tools, and even running small programs designed to indicate the feature set of the shell, C compiler, or desired libraries.

The tool of choice here for variable replacement has, in the past, been the sed stream editor. A simple sed command can replace all of the configuration variables in a makefile template in a single pass through the file. In the latest version of Autoconf (2.62, as of this writing) prefers awk to sed for this process. The awk utility is almost as pervasive as sed these days, and it much more powerful with respect to the operations it can perform on a stream of data. For the purposes of the jupiter project, either one of these tools would suffice.

Summary

At this point, we've created a complete project build system by hand--with one important exception. We haven't designed a configure script according to the design criteria specified in the GNU Coding Standards document that works with this build system. We could do this, but it would take a dozen more pages of text to build one that even comes close to conforming to these specifications.

There are yet a few key build system features related specifically to the makefiles that are indicated as being desirable by the GNU Coding Standards. Among these is the concept of VPATH building. This is an important feature that can only be properly illustrated by actually writing a configure script that works as specified by the GNU Coding Standards.

Rather than spend this time and effort, I'd like to simply move on to a discussion of Autoconf in Chapter 3, which will allow us to build one of these configure scripts in as little as two or three lines of code, as you'll see in the opening paragraphs of that chapter. With that step behind us, it will be trival to add VPATH building, and other features to the jupiter project.

Source archive

Download the attached source archive for the original sources associated with this chapter.