I’m sure everyone reading this has heard the debate over whether that top dog free operating system should be called “Linux” or “GNU/Linux”, but how big a contribution is GNU or Linux to that operating system? As conventional wisdom has it, it’s the availability of applications that make a system valuable, and this is where free software really shines. Linux contributes only about 6% to the cost value of a full operating system, but then again, GNU contributes only about 15%—who do we have to thank for the remaining 79%?! And why don’t we hear them complaining about what it’s called?

This isn’t really about “GNU/Linux”, it’s really about asking “Where does free software come from?” In order to answer that question in any really definitive way, of course, you first have to collect all the relevant free software applications into one giant collection so you can do statistical analysis on them. Wouldn’t it be nice if somebody would do that for us?

Oh, yeah... ;-)

Debian GNU/Linux represents the largest such collection in existence, and with something like 15,000 packages, it comes pretty close to representing the “universe” of free software (or at least, “working” free software, there’s plenty more that isn’t ready for prime time yet, as a quick look at Sourceforge will tell you). Debian will do nicely.

Meanwhile David Wheeler (who you may recall is an occasional contributor to Free Software Magazine), wrote a package called SLOCCount to count “physical source lines of code” (SLOC) in software projects, as well as evaluate them in terms of their “estimated replacement cost if they had to be redeveloped from scratch according to proprietary methods”, represented by their “COnstructive COst MOdel” (COCOMO) costs (which was, of course, originally developed to help managers estimate the cost of proprietary software development projects). This model is convenient to use, because it only needs physical source lines of code as an input, and that’s the easiest thing to collect. There are more sophisticated cost models out there (COCOMO II for a start), but they require more sophisticated input, and are therefore harder to use on a large automated estimation project. So COCOMO I it is.[1]

Observing these two wonderful facts, a group of researchers in Spain decided to have a go at Debian with SLOCCount, and published their results. Their interests are in things like what programming languages were used, but the complete data set can be used to answer some other questions, too. Including the question of who writes free software.

The dataset lists SLOC, package size, and COCOMO estimated cost for each package considered. The packages are meant to cover the entire bulk of Debian source packages, but without overly duplicating code (for example, if two closely related branches exist, pick only one of them). This makes sense, because presumeably the code was only developed once, and so copying didn’t cost much (some would say that's the whole point of free software).

So, in the end, they have 8,560 packages listed for Sarge (not the entire set, but fairly close). Less for earlier distributions, of course.

Now where do they come from? One way to estimate affiliation is by looking for dashed package names: for example, it’s probably fair to count, say, mozilla-thunderbird and mozilla-suite as both being products of the Mozilla project. Even if such a package is actually maintained by a third party, it’s still part of the “Mozilla culture” surrounding the Mozilla project. Many large free software projects are like that: a well organized core with a halo of unaffiliated supporters.

For the GNU project, however, there is a simpler way: they have a list. Which is nice, because they have quite a few projects. Fortunately, Debian is pretty conservative with package names, so if they package, say, “gcc”, there’s a strong chance the package name will contain the string “gcc”, so we can filter. Also, all Debian package names are strictly lowercase (this is policy), so we know exactly what to do to compare. This makes it a snap to cross-reference the GNU package list against the Debian collection.

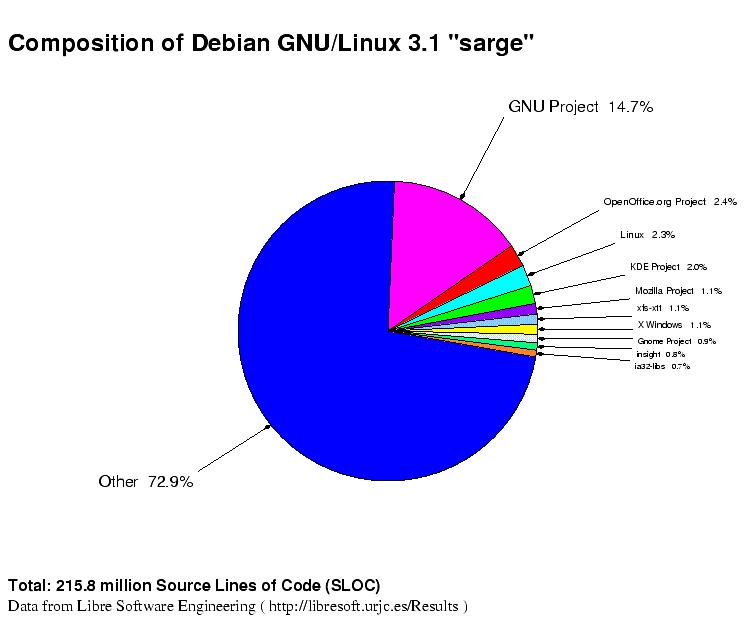

Combining the two techniques, we can get a good picture of who’s behind all those packages. Here it is:

This estimate is by total accumulated SLOC, so it doesn’t draw any distinction between lots of small packages and one giant package. This means, for example, that it overestimates the value of GNU versus Linux. Both are underestimated against the field of smaller independent packages. However, SLOC are a nicely objective measure, so it’s good to start with this.

To get a better picture of the division by value, however, we can use the COCOMO estimated replacement cost numbers. These are a kind of lower limit to the value: because presumeably, you would have to spend this much to create these packages in order to use them. If they were developed by a proprietary organization and then sold, they would have to be sold at prices that would raise at least this much (distribution costs and profits would probably at least double these costs).

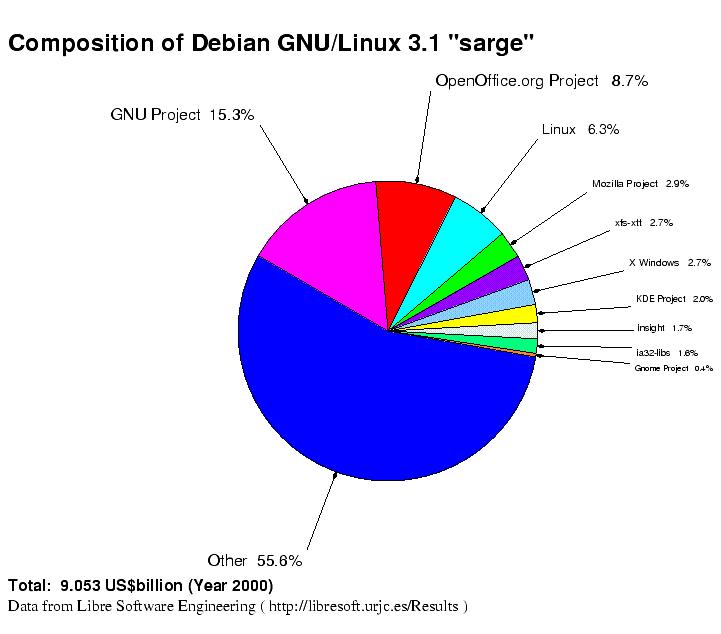

In any case, here’s what that valuation looks like:

You may be a little surprised by the total cost figure at the bottom of the chart. Yep. That's in adjusted Year 2000 US dollars, and is equivalent to approximately one half of the cost to develop the first Space Shuttle [2]. That’s a lot of value. Note of course, this is not necessarily what it actually cost to develop: we assume that free software methods are considerably more cost-efficient, and most of the contributions were “in kind” donations of time, so actual cost is much harder to compute.

But this chart is really about the pie slices: GNU, while being the single largest contributor, still only accounts for 15.3%. Meanwhile, Linux isn’t even number two—that honor goes to a set of desktop applications, OpenOffice.org. More to the point, more than half of the applications come from “the field”—thousands of individual applications created by individuals or companies for their own reasons, not backed by any of the high-profile, high-mindshare free software organizations.

I don’t mean to diminish the importance of the flagship organizations in maintaining free software. But it’s the fleet backing them up that makes the system into the powerful force that it is. The fairest term for what we like about “GNU/Linux” is probably neither “GNU” nor “Linux”, but rather just the “Free Software Operating System”. Free software operating systems are made valuable principally by the contribution of individual developers.

Notes

[1] I should probably mention that David originally used SLOCCount to analyze the Red Hat distribution, and while that’s interesting, it’s not as up to date or as comprehensive as the research I refer to here. Maybe I’ll write about that on another day.

[2] I got this information from transcripts from the Columbia Accident Investigation Board, reviewing the program. The cost adjustment is my own, based on government tables for adjusting the cost of large scale projects (not the consumer price index, which is inaccurate for these kinds of figures). The actual cost in 1980 dollars, was actually less than the figure for Sarge, but that’s just because of inflation. This is the cost to the first flight (of Columbia), and does not include program maintenance costs, which, over some 25+ years of flight is obviously much higher. That’s the fairest comparison I can make because it compares development to development in adjusted dollars. Gives you pause, doesn’t it?

License

Copyright ©2007 Terry Hancock / Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)

Originally published at www.FreeSoftwareMagazine.com.

You must retain this notice if you reprint this article.

Unless otherwise noted, the illustrations in this piece have the same attribution and licensing.