So far, I've identified examples of free, commons-based production of just about every category of pure information product which exists. And that leads to the next question: what about the material marketplace? Can community methods be used to design, prototype, and manufacture physical products? The answer, according to a growing group of open hardware developers is a resounding "Yes!" From computer hardware to automobiles, the open hardware revolution is on.

Myth #1

"Free software works only because software is a 'pure information product'—it can't possibly work for hardware."

Part of this myth is true, of course: you can't really share physical products the way we do with free-licensed information products. That's a fundamental property of information. However, the designs for physical products are just a special kind of information product, and they can be shared.

Open Hardware Electronics

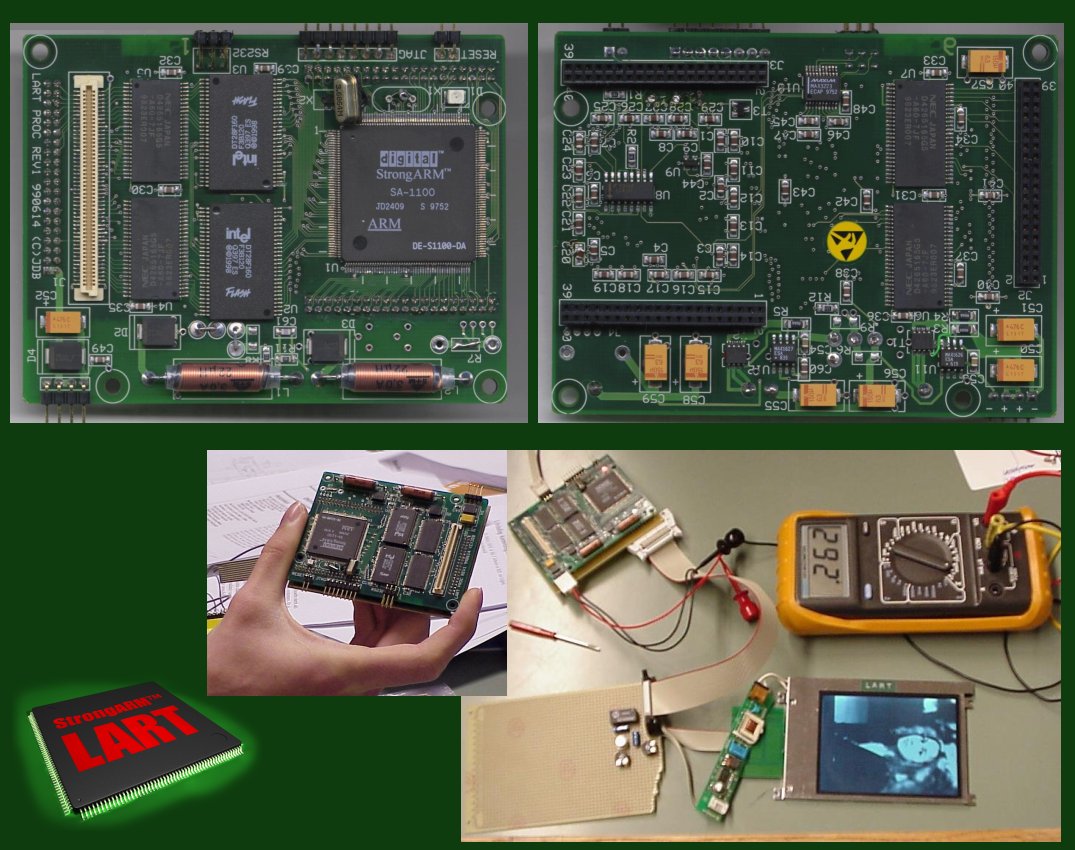

Although there have been "homebrew" projects for many years, one of the first really successful complex electronic designs to be released under a free-license was the LART[1]. It was an embedded ARM-based computer designed for set-top multimedia boxes (but of course, it could be adapted to many uses). The complete design was released under a GPL license, including all of the plans and CAD/CAM files used to construct it.

There was one problem, which was that the CPU itself was not a free-licensed product, and it was eventually discontinued, which essentially orphaned the LART design. Although work continued for some time on new designs, the project's website hasn't been updated since 2003. Closed design and limited availability of important components is a serious problem for higher level designs.

Getting Inside the Chip: FPGA Designs

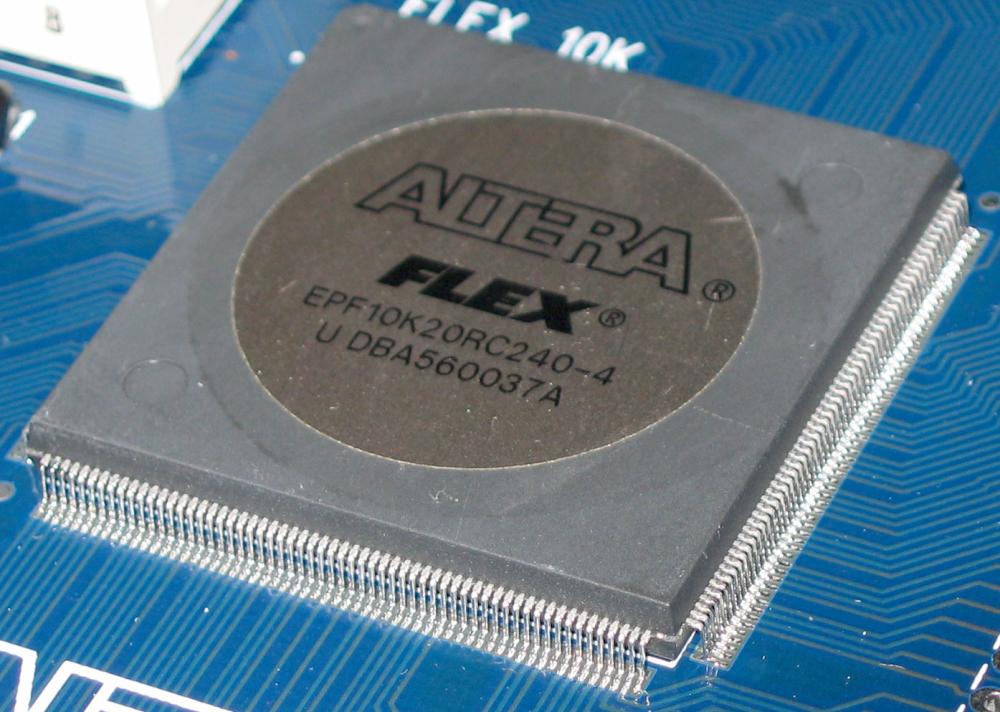

Much of the recent success of popularizing free hardware design has come from the introduction of "Field Programmable Gate Arrays" (FPGA). These chips store huge arrays of logic gates whose connectivity and functionality can be altered in software as if they were memory addresses. This allows hardware description languages (HDL) to be used to describe the functionality of a circuit, then compile (or "synthesize") the result into an actual gate layout which can be loaded onto one of these chips. Xilinx and Altera are the biggest names today in FPGA manufacturing. Once a design has been tested in FPGA, it is possible to create "Application Specific Integrated Circuits" (ASIC) made for much lower unit costs. Thus an FPGA serves a similar role for chip designers as breadboarding does for printed circuit board designers.

Joseph Black, a developer on the Open Graphics project described the experience of working with FPGA designs and hardware description languages in 2008:

"When I did a short course about FPGAs and VHDL (a hardware language) I found to my surprise that I could download a datasheet of any chip I found and make my FPGA do the same job. And this is not very difficult. I tried a certain 8 bit RISC processor, and after two months of work, I realized that I had implemented a sizable portion of it. And it ran fast! So fast, I could envision that it was possible to run their chip faster on my FPGA. Then I searched the net and found others had already begun similar work on other chips and designs and I then had a lightbulb moment. Hardware design was now possible for the average man.

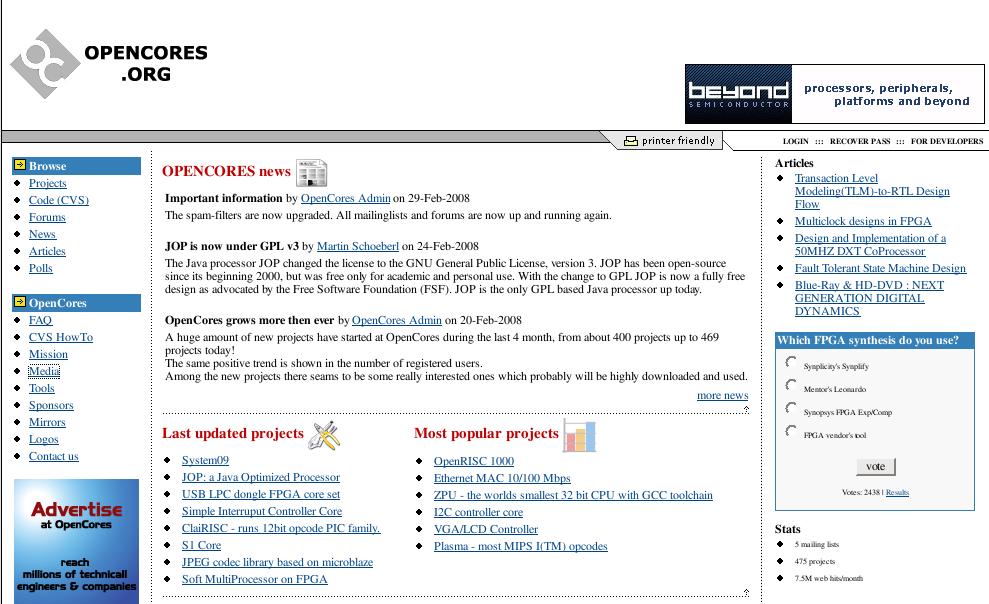

"With the ability to create and test open hardware designs, it's possible to develop a bazaar development community around open hardware chip designs. Such a site is Open Cores." —— Joseph Black

Closed design and limited availability of important components is a serious problem for higher level designs

The Open Cores[2] project now hosts approximately 280 open hardware chip "cores", varying in complexity from frequently-used interface and register logic up to entire microcontroller and microprocessor systems (several legacy processor specifications have been implemented as well as some new designs such as the "OpenRISC 1000" CPU, which has already seen some commercial applications).

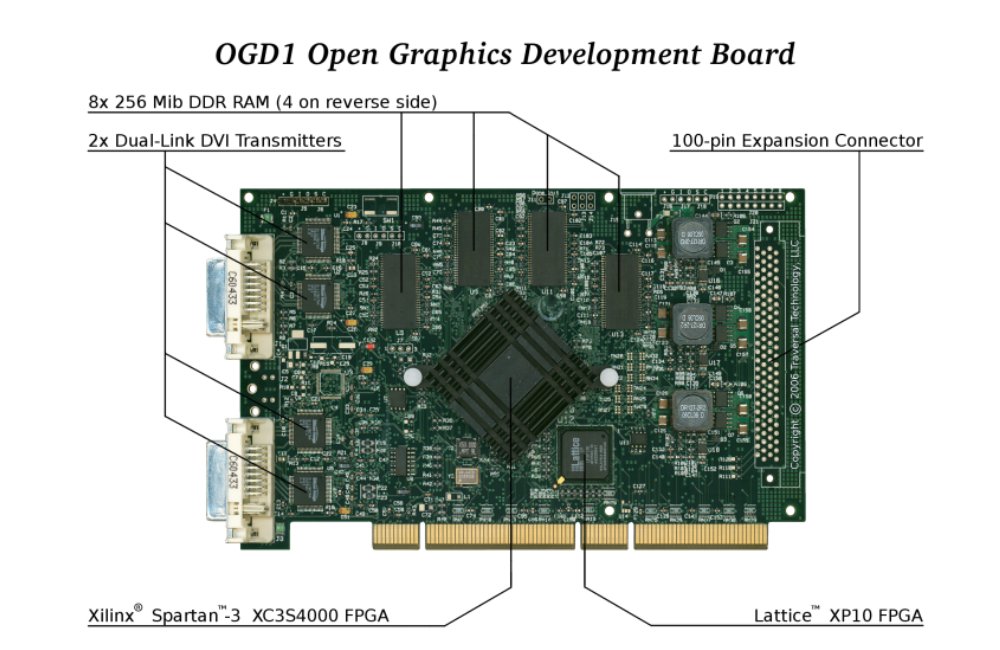

Taking FPGA a step further, the Open Graphics project, started by Timothy Miller of Tech Source (and now of Traversal Technology), aims to design a high-speed 3D-accelerated graphics subsystem, for tasks such as 3D design, data visualization, and desktop support (as well as some games). As a first step in the project, the Open Graphics community has completed design of a specializaed FPGA development board that will be usable as a graphics card when its FPGA is loaded with the Open Graphics Architecture (OGA).

Once the OGA is reasonably complete, Miller plans to raise funds to produce the design in a much cheaper and somewhat faster ASIC version, which his company will sell primarily to embedded computer manufacturers. As a spin-off, however, the project will also design a 3D graphics adapter board targeted at free software operating systems, since it will have complete free-licensed documentation and free software drivers.

Realizing Open Hardware

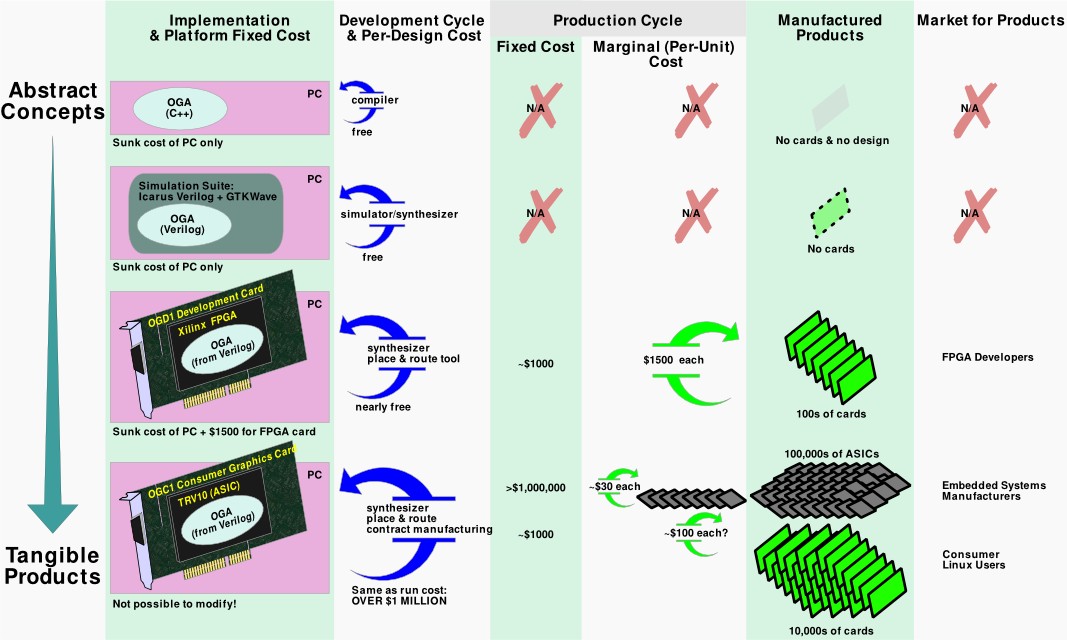

Because of the realities of hardware manufacturing and the resulting cost structures, it's often a challenge to actually get open hardware made, once it's been designed. This is usually because manufacturing setup costs are high, while marginal production costs are low: the classical reason for mass production.

Strategies differ, but the Open Graphics project presents a practical example, illustrated in figure 5.5.

First the project will create the OGD1 (this was essentially completed in 2008, although at the time of this writing in 2009, the project is still raising funds to build the first run). Then the project will develop the Open Graphics Architecture on this platform, while selling the OGD1 cards (which are powerful, low-cost general-purpose FPGA boards in addition to their special input/output features).

Once the architecture is complete, the project hopes to use seed capital from the OGD1 sales and venture capital investment to produce a modest-sized run of ASIC chips based on the design. These will be sold mostly to embedded developers, for whom the open source design is a strong selling point.

Even a small number of these chips will provide ample supplies for short runs of an ASIC-based "Open Graphics Card", designed to be competitive enough to attract the market of free software operating system users.

Production runs and collective purchasing are a common problem for open hardware projects. Even runs of circuit boards often need to be in the hundreds or thousands in order to be cost-effective (figure 5.6). Despite the difficulty, however, a number of projects manage to get their products manufactured.

Less and Less Ephemeral: Open Hardware Cars

So far, however, we haven't strayed far from the realm of computers and computing. These are still quite ephemeral "high information content" designs. But open hardware can go much further.

So far, few projects self-consciously identify themselves as "open hardware": there are a lot of "homebrew" designs out there for technology ranging from windmills to airplanes which are usable for hobbyists, but limited somewhat in collaboration because no consideration has been made of the licenses.

Three separate groups have hit upon the idea of developing a next-generation automobile design using open source methods

However, some people are getting the idea. For example, three separate groups have started attempts to develop a next-generation automobile design using open source methods: the "OScar" project, the "Open Source Green Vehicle", and the "C,mm,n" project. Arising from different communities, each has a unique character which is worth exploring.

OScar[3] is a true community-driven project, very much in the amateur spirit. The project's originator, Markus Merz, was motivated to do the project largely out of a desire to create something physical using bazaar methodology. The result is less a car development project, and more a forum for sharing ideas on car design and construction. Very likely, the result (or results) of the OScar project will be in the form of "kit cars" which can be manufactured using fairly simple tools, by individuals or small organizations, though it's still unclear exactly what the project will try to produce.

The Society for Sustainable Mobility has proposed creating an "Open Source Green Vehicle" (OSGV[4]) primarily out of a self-conscious desire to counter perceived market pressure for the status quo, and the community reflects this outlook. The license is not a true free-license, as it prohibits manufacture of the design (although it's not clear that such restrictions are enforceable). The rationale for this is based in liability and safety concerns (and a faith in professional training): they claim that only "professionals" should do such tasks and fear that people might "kill themselves" by attempting to manufacture the cars themselves.

"These laws are not designed with the Open Hardware ecosystem of loosely organized design groups and small, independent manufacturers in mind, and they could well become an obstacle"

This attitude is a big contrast from the do-it-yourselfer attitude of the OScar project, but it is not an unfounded fear, and something that free-licensed hardware designers must consider in licenses for high-powered equipment. As Lourens Veen of the Open Hardware Foundation reflected in a 2008 interview:

"One possible problem is a legal one. As the devices we buy have become more complex and more proprietary, their manufacturers have become more powerful. In response to that, consumer protection laws have become more and more strict, especially in the European Union. These laws are not designed with the Open Hardware ecosystem of loosely organized design groups and small, independent manufacturers in mind, and they could well become an obstacle. There are precedents for more Open Hardware-friendly legislation however, such as the Single Vehicle Approval that is required for kit cars in the UK, and the 'experimental' category air worthiness certificate in the US." —— Lourens Veen

The OSGV site does suggest that its restrictions might be lifted in the future, and the overall focus on community involvement in the engineering process merits mentioning on the subject of open hardware. The OSGV focuses on a "kernel" of drive train development, with localized projects developing the "look and feel" of the designs with a focus on regional car markets.

Finally, the C,mm,n[5], with its too-clever-for-its-own-good name, was born in a university engineering environment at TU Delft in Holland, providing it with a strong brick-and-mortar support system. Thus, although the project started later than OScar, it was able to produce a non-working prototype of the design for display at the Dutch biannual AutoRAI show in 2007. The group hopes to have a working prototype for the 2009 show.

Open Hardware Goes Mainstream

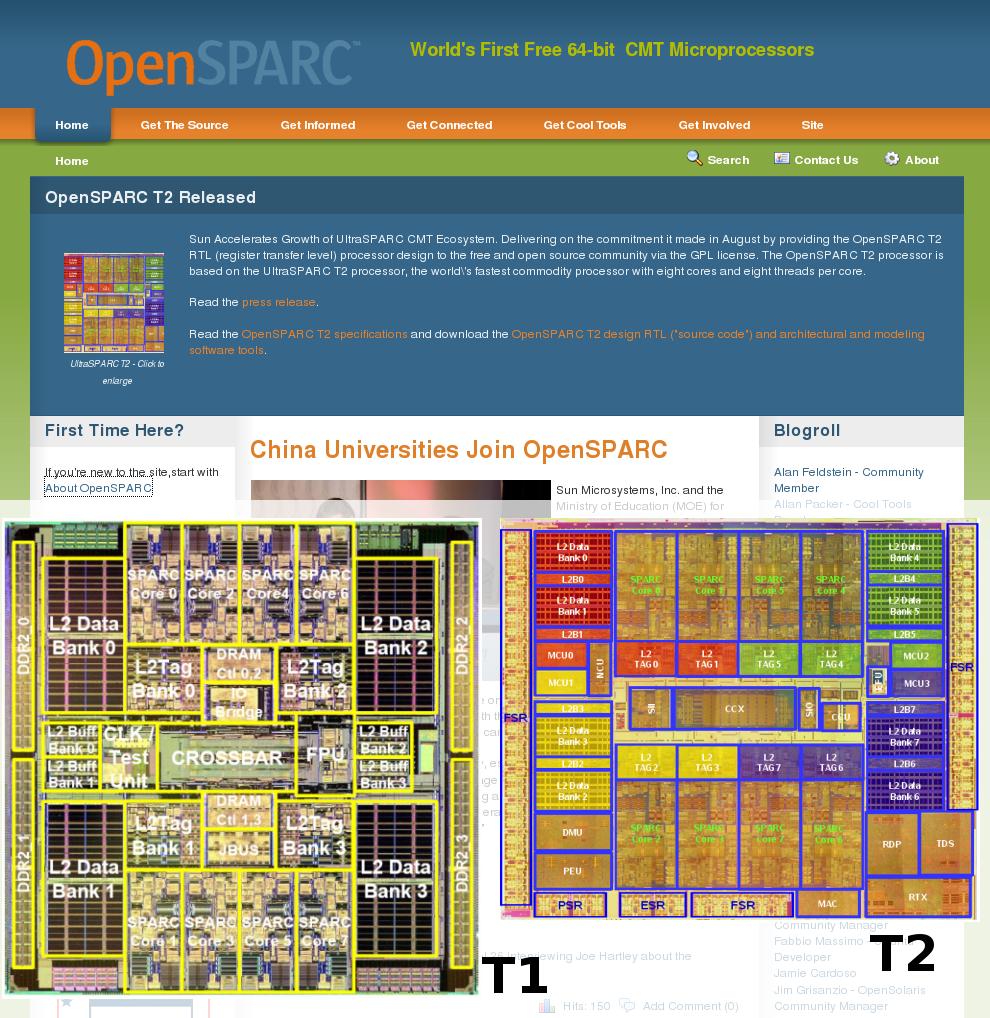

With so may pioneering new projects out there already, it shouldn't come as a huge surprise that some major companies have decided to join the bandwagon. Sun recently released the source code for their "UltraSPARC T1" and "UltraSPARC T2" multi-core microprocessors under the GPL. The resulting design is the OpenSPARC, which has now grown a small hardware design community.

Although it is clear that open hardware has some special challenges, real projects succeed at overcoming them, and open hardware is clearly a growing phenomenon. The strongest areas have understandably been in the area of computer hardware, but there's no fundamental limit to what can be created by commons-based communities using free-licensed hardware designs. The same bazaar development rules apply to hardware as for software: both provide a smoother environment for collaboration on truly innovative designs.

Notes

3(http://www.theoscarproject.org)

Terms

ASIC: An Application Specific Integrated Circuits is a chip which has an orderly array of logic devices on it, which can be "programmed" at the factory, using a hardware description language, similar to the ones used for FPGAs

FPGAs: Field Programmable Gate Arrays

hardware description languages or HDL: Formal languages for specifying the requirements for a logic circuit. Specialized programs can "synthesize" a circuit which meets the specification, following formal design rules, in much the same way that a compiler can create binary code from source code. Thus, HDLs can be thought of as "source code" for digital integrated circuits

open hardware: Open Hardware is hardware whose design documentation is available under a free license, an analog to free software