For many years, there has been a growing concern about the emergence of a "digital divide" between rich and poor. The idea is that people who don't meet a certain threshold income won't be able to afford the investment in computers and internet connectivity that makes further learning and development possible. They'll become trapped by their circumstances.

Under proprietary commercial operating systems, which impose a kind of plateau on the cost of computer systems, this may well be true. But GNU/Linux, continuously improving hardware, and a community commitment to bringing technology down to cost instead of just up to spec, has led to a new wave of ultra-low-cost computers, starting with the One Laptop Per Child's XO. These free-software-based computers will be the first introduction to computing for millions of new users, and that foretells a much freer future.

Myth #4

"You and whose army? There just aren't enough people into this kind of thing."

Free culture is no longer a fringe phenomenon.

One Laptop Per Child

Kofi Annan, former Secretary General of the United Nations, suggested the idea a few years ago: a project to change the way that children around the world learn. Nicholas Negroponte, a professor at MIT decided to tackle the problem, and in time, after much review of the options, this turned to a constructivist learning solution: provide the children with a tool for "learning learning" (as education expert Seymour Papert would put it). The design selected is a "laptop" computer, though the term has to be used somewhat loosely, because the OLPC XO 1, being designed for a totally different mission than the typical business traveller's laptop, is not like any prior design[1].

One of its principle design criteria is that it must be very, very inexpensive. The target was US$100. The first units cost closer to US$200, though it is hoped that the cost will drop as the component prices come down and the design is further stabilized. The project has committed to lowering costs rather than increasing performance, since the whole point of the OLPC laptop is to create something that Third World countries' education ministries can afford to purchase for the children in their countries.

Every single piece of software on the machine will be free-licensed open source software—right down to the firmware BIOS, which will be OpenFirmware, written in Forth

It's not such a good idea to make a computer like this using proprietary software for several reasons. First of all, you obviously can't afford to pay the licensing fees on 100 million copies of Windows—such fees would cost more than the hardware! Second, even if subsidies were offered to make it affordable, the choice would introduce new constraints on the design and the brittleness intrinsic to any single-supplier system. Finally, since the whole point is to help kids in exploration learning, it's counterproductive to hide the mechanism—open source for the operating system is just another part of the learning experience.

So, it should be no surprise that the OLPC laptop will run Linux. In fact, the machines contain a complete free software system—right down to the firmware BIOS, which will be OpenFirmware[2], written in Forth. Because of the complexity of shipping source code for all of the software on such tiny, storage-constrained computers, the team also decided to write a huge amount of the system in Python, an interpreted programming language that greatly simplifies this requirement. With Python, the source is the working program, so there is only one thing to distribute; the source is particularly easy to read, even for grade schoolers; and no compiler or build system is required for them to modify and use the software on the computer. Changes are reflected immediately, at run time.

In fact, the OLPC laptops are designed to facilitate this kind of exploration as much as possible. Developing software is one of many "activities" which a child is invited to explore through the machine's "Sugar" user interface[3]. Every running program will be designed to allow the child to press a simple "view source" key to see the Python code behind it (you may have noticed that most web browsers have a feature like this, making HTML highly accessible even to "non-programmers" around the world).

Developing software is one of many "activities" which a child is invited to explore through the machine's "Sugar" user interface

The consequences of this design decision are staggering and inspiring. Around the world, perhaps by 2020, there may be as many as 100 million children, ages six to ten, with a complete, easy-to-use Python programming environment and an operating system full of fun programs to tinker with. It's hard to imagine any child that wouldn't be drawn into that.

For the sake of argument, though, imagine that in fact only one child in a thousand genuinely gets involved and reaches a point were we would legitimately call them an "open source developer". That's 100,000 people. Remember: Debian GNU/Linux, which we've already seen could be valued at $10 billion or more, was built by many fewer people.

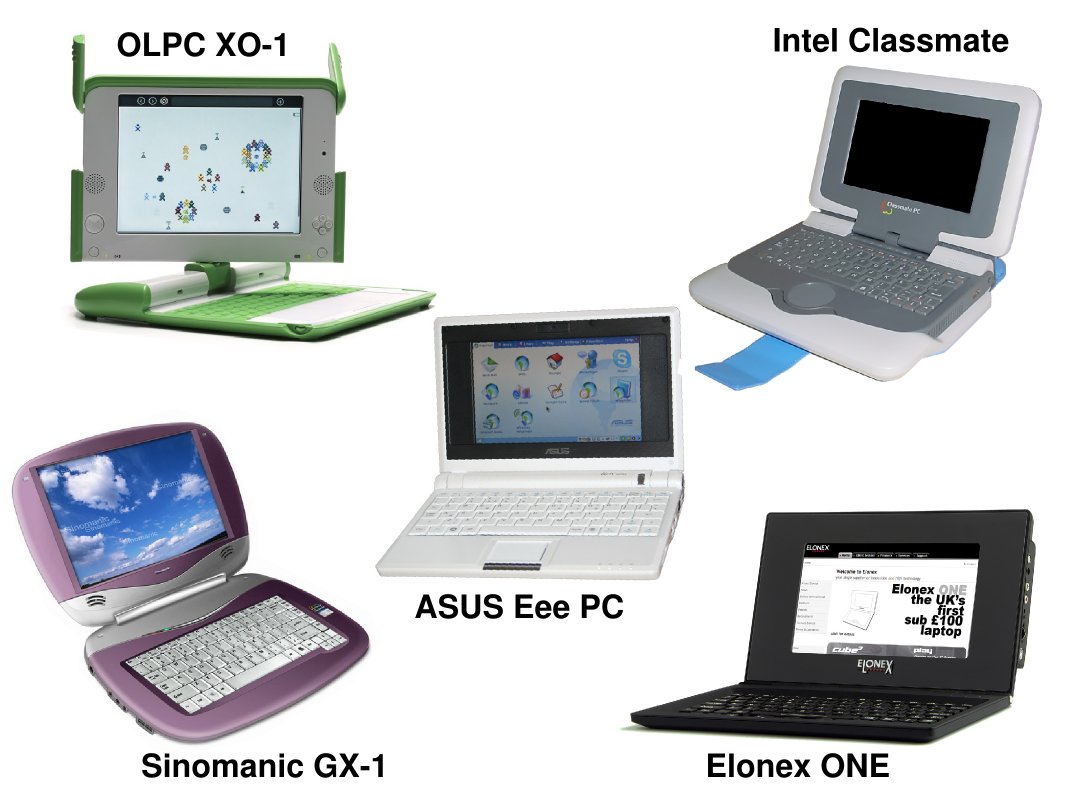

Still, the OLPC project itself has also been in the press for less positive reasons. There have been some accusations of mismanagement, and personality conflicts have arisen. There was a falling out with Intel, and the organization is currently planning some management reorganizations. Some fear that it won't attain its lofty goals. But in the long run these are not very important considerations, because even if OLPC itself fails, the mission concept has already been proven, and it's the mission that matters. If not the XO, then some other ultra-low-cost machine will be deployed throughout the world to fill the same niche: several competitors have already entered the market.

A Whole New Kind of Computer Market

Enough people in the developed world have been impressed with the XO's design to make mainstream manufacturers and designers take notice. Clearly, there is demand for a $200 to $400 computer that does what the XO does. And since the production and distribution chain for the OLPC is hampered somewhat by the specifics of its mission, commercial developers are stepping in to close this market gap.

A new array of low-end laptop computers, based on flash-memory, power-miser CPUs, extremely rugged design, and GNU/Linux operating systems are being built and marketed to supply the new demand.

Fortunately, these computers will have almost the same impact in richer countries that the XO will have in poor ones: millions and millions of people will be exposed to an out-of-the-box experience driven by GNU/Linux and free software. Such users won't ask "why should I switch to free software?", but "why would I ever switch to anything else?" The stick-with-what-you-know motivation is strong, and that advantage will now apply to free software.

Millions and millions of people will be exposed to an out-of-the-box experience driven by GNU/Linux and free software

But what's more interesting is that, with so many more people (and so many more kinds of people) exposed to it, the potential for new involvement, new ideas, and new software development also increases. With ten-fold more users, comes ten-fold more potential new developers. And, of course, every itch scratched serves ten times as many people: which means there's also a larger pool from which foundation activities can draw.

The OLPC in 2009

In 2008, OLPC found itself considerably short of its goals, and much finger pointing and acrimony ensued. It was probably inevitable that something like this would come up eventually. The OLPC project operates in one of the harshest political environments imaginable: not just education and not just the developing world, but both in one package!

The OLPC project compromised ideological purity by offering laptops with a dual-boot GNU/Linux and Windows XP system to those potential buyers who insisted on being able to run Windows. This may well have been the right decision, too, though it heartily annoyed some people in the free software community.

Tensions between industrial sponsors, the OLPC organizers, and the community of free software developers produced some sparks, and the result was a substantial reorganization. Sugar left the official OLPC project, becoming an independent project operated by Walter Bender and others as "Sugar Labs"[3]. This was almost certainly the right move, since it put the community in charge of the community project, as well as increasing its visibility.

Nevertheless, the OLPC project—and now I am speaking of the whole movement surrounding the One Laptop Per Child mission, not just the organization that started the project—is getting back on track, and may do much better after this transition, though as of this writing in 2009, it's really too early to tell for sure).

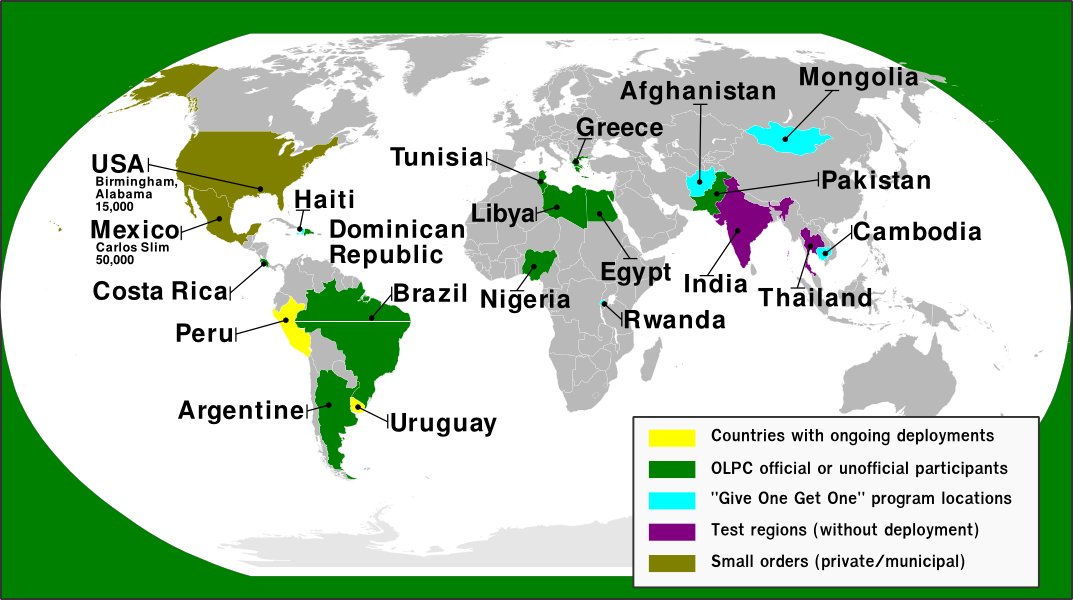

Right now, the OLPC project stands at about half a million units either deployed, or in the process of being deployed worldwide. That's about 5% of the stated target for the end of 2007 (over a year ago), and only about 0.5% of the original stated objective of the OLPC project, which was closer to 100 million (about 1/60th of the population of Earth). Presumably the real target (every child on Earth) is an even higher figure. Clearly OLPC has fallen far short of its progress goals.

Nevertheless, a lot of good has been done, and it's likely that a lot more will be.

-

OLPC's XO is still the freest thing going: free BIOS, free operating system, free window manager, free applications. That some of them will carry Windows as well is a detail: deploying free software is a lot more important than hurting Microsoft

-

Sugar has broken away from the OLPC organization, taking Walter Bender and others with it, as a new entity called "Sugar Labs". It has its own independent online presence and community now. A series of more portable builds has been an outcome of this process.

-

Nevertheless, we now have choices. The XO was popular enough in the developed world to spawn a raft of imitators: a whole new class of computer, popularly called "netbooks".

-

Sugar runs on those imitators, on the XO, and on refurbished or new computers anywhere in the world. Whatever you might think of the XO as the deployment vector, Sugar is a free software tool that all free software advocates can support

-

Sugar is 100% free software. Even the Squeak/Etoys package has gotten over whatever licensing quibbles it was encumbered with. Today, it's even being admitted into Debian main, although the administrative hurdles will take a few months to clear.

-

OLPC is seeing bigger orders. Evidently, Negroponte's Windows gambit is working.

The break-up itself is somewhat enlightening for the purposes of this book. Note that the community needed to get better control of the software development effort in order to feel ownership of the project, and therefore more of a responsibility to update it. Note the tension created by the different cultures of the business and commons-based enterprised worlds. Finally, notice how the independence created by free licensing allowed the software project to migrate smoothly to community control, thus surviving what might have become a disastrous failure had the whole thing been managed as a proprietary enterprise.

Pioneers and the New Wave

What this will mean, of course, is that the present "free culture" is really just the "pilot project". The real social phenomenon is yet to come. And if the present array of free software developers, open hardware hackers, and free culture producers can shake the world as much as we have already seen that it has, then it's clear that this new wave of more than an order-of-magnitude in scale will quite simply re-make the world.