A constant pattern in the corporate environment is the gathering of resources, but with the free exchange of information inherent in commons-based projects, the pattern of choice is the dispersal of resources. This presents certain design challenges, which manifest themselves in the Unix-style "small sharp tools" approach to specialization; encourage "bottom-up design"; and most importantly require easy-to-obtain, shared, free standards for data interchange between programs. When every train car is to be made by a separate builder, it is essential that the rail gauge is constant and known.

RULE #3: Divide and Conquer

For large projects, establish a platform and interface standard, making it easy to contribute small, independent, pluggable elements

Concentrate on just one of these elements yourself

Community based project participants only tolerate very limited "buy-in" to platforms and standards and thus seek systems that will let them work more or less independently, with only the minimal interface requirements being placed on them by the platform.

Whatever interface requirements do exist must be explained succinctly and clearly so as to make the barrier to the platform as low as possible.

As much as possible, all new platforms should take advantage of existing interface standards, both to allow direct use of existing design resources targeted for those standards, and to minimize the learning curve of new standards as they arise.

Single projects should try to do just one thing very well, rather than trying to provide lots of features. This promotes use of the package as well as the platform it is built on, and encourages other features to be contributed by others.

Deconstructing "GNU/Linux"

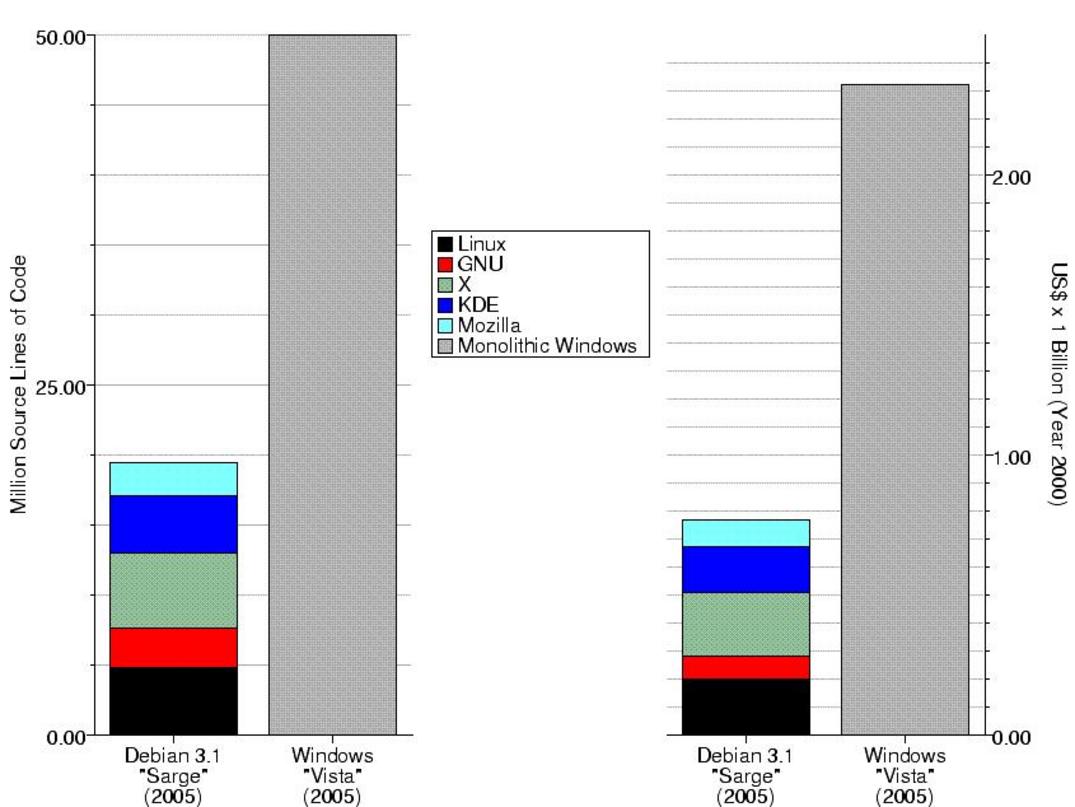

When I tried to compare the size in "source lines of code" (SLOC) between "Debian GNU/Linux 'Sarge'" and "Windows Vista", the first problem to arise was that there really is no direct free software analog to the "Windows operating system". Instead of one single monolithic development project, the free community produces a swarm of smaller projects. However, by choosing a popular selection of projects, it's possible to build an "equivalent function" alternative to Windows, as presented in figure 10.1.

This figure certainly dispels the notion that Windows code might be smaller than Debian because of inefficiency in the free software code (indeed it suggests the opposite might be true), but what it also shows is a pattern of specialization wherein functionality is separated as much as technically possible and each functional unit is provided by separately-managed projects. Instead of one "operating system" project (for an ever-expanding definition of "operating system") like the proprietary "Windows Vista", the equivalent free software functionality is a "stack" of several completely-independent projects, each with a more narrowly-defined range of functionality.

Instead of one single monolithic development project, the free community produces a swarm of smaller projects

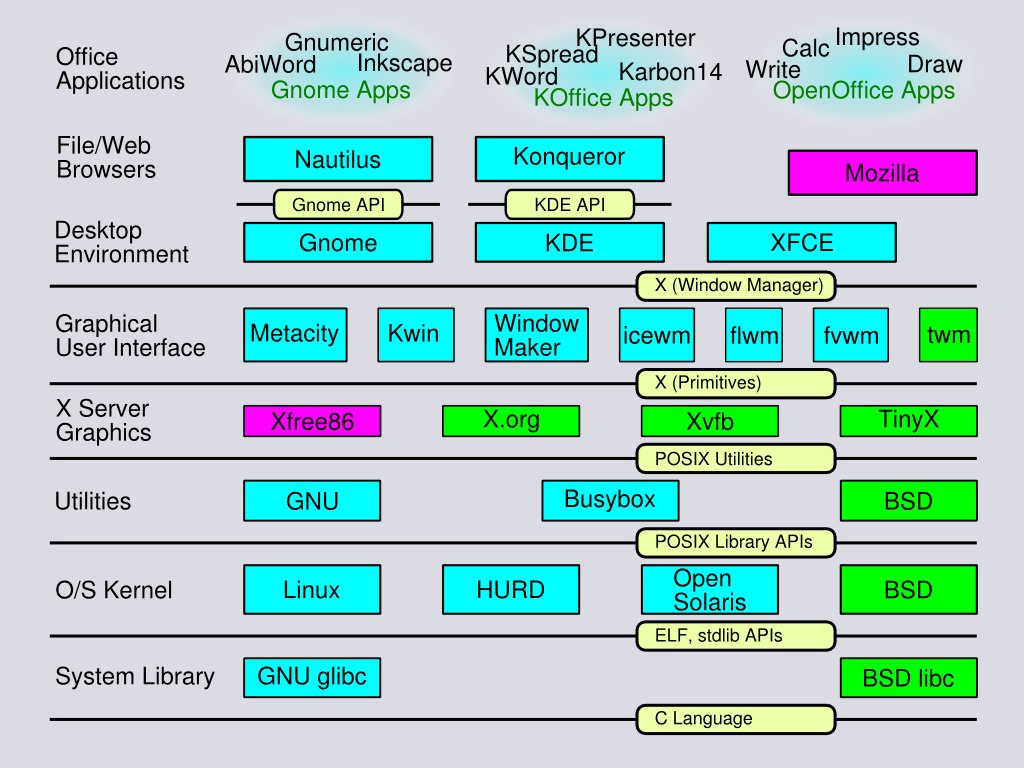

One thing figure 1 does not show is the range of choice that is also possible. This particular stack (glibc + Linux + GNU utilities + X.org + KDE + Mozilla) is only one popular choice out of many. This choice is made possible by the fact that each layer in the stack adheres closely to published interface standards. With relatively few problems, any of the stack layers can be swapped out with alternative programs providing similar functionality. Figure 10.2 shows an assortment of the options available. Even considering that this not a complete list of objects, the number of possible combinations (over 2000) is staggering!

Some of the combinations shown (e.g. BSD libc + HURD + Xvfb + Kwin + XFCE + Nautilus) are pretty unlikely to be in actual use and therefore may be very buggy, but they should be possible. The greatest bottleneck is actually the X Windows system, since all of the examples given here are really forks or parts of the same project. Of course, given that these are free-licensed projects, one might wonder why anyone bothers creating "duplicate" functionality.

The truth is, though, that as with programming languages or word processors, there are a lot of fine differences which affect personal preferences among users, and there are fundamental differences in design philosophy and tools among developers. Additionally, there are disagreements about which licenses are "free enough" for certain parties' interests (e.g. there probably wouldn't have been a separate BSD libc, except for the desire of BSD developers to avoid dependencies on GPL software).

The use of smaller, more highly specialized programs, rather than big flagship applications, is a long-standing Unix environment tradition

The use of smaller, more highly specialized programs ("small sharp tools"), rather than big flagship applications, is of course a long-standing Unix environment tradition (even for proprietary Unix). It represents good engineering design in any context. But the pressures of expediency near the end of release cycles in the commercial proprietary software world tend to cause a breakdown in this engineering discipline. At the same time, the distributed and relatively disorganized community development environment, lacking any formal command structure, cannot sustain much in the way of large-scale coordination efforts. Thus, the community's very nature tends to reinforce the important engineering design principle of "separation of concerns".

"Too Many Cooks Spoil the Broth"

The wisdom of capitalist/corporate industry is to gather resources and put them under the control of one strong leader. Regimented control of the entire industrial process is thought to be essential to avoid conflict and waste when many people are trying to work together. Our capitalist economic system is designed to support this idea by providing means to concentrate wealth in the hands of those who are perceived as having the best chance of using the resources successfully and beneficially for society. Indeed, the system is named after this practice of "gathering capital".

In addition of course, the system is competitive, creating a situation where corporate entities with sufficient capital often reproduce the same basic effort and the redundant products compete for market share. The theory is that the one that wins the competition will be a better product, thus encouraging corporate entities to put in their best effort and the public is provided with superior products.

Unfortunately, this depends on the public being able to tell when one product is genuinely better than another, and with things as complex as software, the comparison process can be extremely difficult. As a result, various proxies and superficial comparisons become more important than the core functionality of the software, and maintaining the extra burden of "feature wars" detracts from the engineering effort to produce good code and concentrate on the features which are most needed. Perceived value also relies heavily on "psychic value" established through advertising and on "network effects" after a winner begins to emerge. Thus a product may emerge quickly on the basis of a completely irrational value proposition, then hold that position due to the need for compatibility with others who are already sold on it.

The wisdom of capitalist/corporate industry is to gather resources and put them under the control of one strong leader

The most familiar example is probably the Microsoft Windows operating system, but there are many others. This is not a peculiarity of bad business practices from just one company, but rather a broad systemic fault caused by the incentive system and poor metrics available to the consumer—simply because the product is so complex and its inner workings are so secret that it is really impossible for a buyer to make an intelligent decision about which system to buy into.

In software, this approach leads to enormous flagship software applications with highly complex internal structure, great difficulty of maintenance, and poor interoperability with competitors (probably by design).

"Many Hands Make Light Work"

The wisdom of commons-based peer production is to require few common resources and make the ones that are needed as publicly-documented as possible and as available as possible to as many people as possible. This eliminates barriers to entry and participation on projects—which, without a strong profit motive (lost because copy sales are not profitable for free-licensed information products), is essential to the success of community-based projects.

Money can be made by users of a free licensed product, but they have limited ability to profiteer from it because they cannot exclude others from competition in order to maintain the limited monopoly position required to raise prices and thus offset their capital investment in the product. Instead, the contribution of individual participants in a free design project has to be regarded as part of their simple "overhead" costs, and thus, each individual can only afford a much smaller investment.

This makes it essential both to contain the effort required so that it does not undermine the participant and also to leverage that effort as highly as possible by exploiting the contributions of others. By contrast, competitive advantage in the design serves little purpose since it has already been given away. As a result, the participants are motivated to minimize their collective redundant effort and maximize interoperability and extensibility of their contributions.

The wisdom of commons-based peer production is to require few common resources and make the ones that are needed as publicly-documented as possible and as available as possible to as many people as possible

This makes it critical to divide projects up into small manageable chunks; to make those chunks independent enough to allow development by unaffiliated parties; and to make all remaining interdependencies readily-available public knowledge. These requirements impose strict engineering disciplines of "separation of concerns" and "design by contract" in project designs.

Even in the case of "competing" packages like KDE and Gnome, which do essentially the same thing, there is communication of ideas. If something works well enough in Gnome, it will tend to be borrowed into KDE. Thus while competition does serve a positive role in allowing different ideas to be tried, and in serving different users with different needs and preferences, it does not lead to the negativity of a "zero sum game". Instead, a new "competitive advantage" may simply be ported from one package to another (as a quick example, look how quickly "window tabs" spread among major free software applications).

Common gauges and social codes

Standards-based interface design and high levels of component-ization mean that projects which might otherwise be seen as single very large projects deconstruct into dozens or even thousands of tiny projects. Ideally each such project falls within the capability of a single independent developer (in reality some engineering problems are hard to break down, and small formal or informal teams are needed).

Of course this imposes a kind of design discipline which is extremely beneficial to the long-term engineering stability of the systems so-designed, and which is nevertheless extraordinarily rare in the products of corporate industry. It is this design discipline which is largely responsible for the perception of engineering superiority and practical robustness of open source software designs: systems of many interacting, interchangeable parts are much more fault-tolerant than "brittle" systems designed as monolithic pieces with high levels of interdependence between separately developed components.

Ideally each project falls within the capability of a single independent developer

As a result, the free software community is largely organized around data standards (like XML, HTML, SVG, ATOM, JSON, or ODT etc) rather than individual software packages (like MS Word or Adobe Illustrator). To hide such a standard or obfuscate it any way is seen as obstructionist and unconscionable (an attitude which is unfortunately not so prevalent in other engineering disciplines where standards are often only available for purchase—and are sometimes very expensive, effectively shutting-out small-scale developers).

Troubleshooting Tips

#Factor, Factor, Factor

Especially if you come from a systems-engineering background, you may have thought of your project as one giant machine to be built. Dividing the problem up into functional blocks is something you usually think of as an internal engineering problem.

Unfortunately, such projects require a lot of "buy-in" from potential developers. They have to overcome the learning curve before they can begin to contribute to your project (or even use it). This puts off a lot of potential contributors who might really support your project if they could try it a little piece at a time.

Spend some time brainstorming about the various pieces of your project. What else can these things do? Try to break the project up into a lot of smaller, multi-purpose tools; make them as independent as possible; and present each of these to the community as a separate project (this kind of reorganization is called "re-factoring").

It's okay to describe your "master plan" somewhere, but keep the emphasis on the individual components. Other people will contribute to them for their own reasons.

By far, my own most successful projects have been "spin-off" projects like this: ideas I developed because I needed them as components, but which could be re-used by others.

Putting It All Together

It has been said that the structure of programs mirrors the structure of the organizations that created them, and this is true of free software as well as proprietary. A loose aggregation of developers with different interests and needs and very limited individual resources naturally tends to produce a large collection of narrowly-focused programs. A practical necessity of this structure is the use of well-defined, freely-available, and easy-to-implement standards.

These two patterns of design, imposed by the natural structure of commons-based development, happen to coincide with important principles of good engineering design (particularly the separation of concerns and well-defined interfaces) which can be hard to enforce in a commercial environment where time-pressure and expediency of communication can put short-term gains ahead of long-term stability.

With such a chaotic sea of unaffiliated project development, though, how is it that large scale structures (such as entire operating systems and distributions) arise in free software?

It has been said that the structure of programs mirrors the structure of the organizations that created them, and this is true of free software as well as proprietary

In the commercial environment, organization comes first: A "manager" sets goals, makes guesses about the difficulty of implementation, and assigns various "teams" to overcome them. By contrast, in the community environment, organization comes last: vague goals are suggested (often by high-profile community opinion leaders), self-selected "developers" choose to solve some of the intervening problems, and then finally "packagers" search for already existing packages; test and ensure interoperability with other packages according to selected standards and policies; and then build a "distribution" or "stack" which combines them into a working whole.

Hard as this is in practice, it is remarkable that it is generally feasible. As long as the individual pieces have been designed against good interface specifications and tested against good implementations of them, the chance of fitting the pieces together into compiled, consistent, and functional code is quite high. Clearly some software-writing must happen in this adaptation task, and occasionally requests get back to the original developers, but for the most part the integration process is kept simple.

"Packagers" like the Debian Project are, in a way, the greatest heroes of the free software movement, because they are the ones who make the system "just work", despite its patchwork origins.