In a recent article, Ryan Cartwright argued that free software isn't playing the "same game" as proprietary software is. He's right—but that begs the question: what game is GNU/Linux playing?

Thirty years of proprietary software thinking have conditioned us to think that marketshare is a critical measure of success, and so we've convinced ourselves that we have to "win" against Windows in order to "succeed". But this is simply not true. GNU/Linux can be a very great success even if it never achieves more than 1% of the installations in the world. The reason is the difference between "power" and "freedom".

The freedom metric

"Success" means something very different when your goal is "freedom" than it does when your goal is "power". Proprietary companies exist to make money, thus power over the marketplace—the ability to demand tribute (in the form of Windows license fees paid to Microsoft)—is the essential definition of success. For free software, however, the goal is to provide the freedom to choose and use free software (the GNU/Linux operating system and its associated universe of applications). For those who seek to create freedom, such monetary tribute is a nice form of applause, but it is not essential to success.

"Success" means something very different when your goal is "freedom" than it does when your goal is "power"

Freedom cannot be forced on people. Freedom to choose GNU/Linux means also the freedom to choose Windows as well. We can argue that it's a bad deal, but we don't have the right to force people to choose one over the other. Nor should we pass value judgements on them for their choice: we don't know the basis of their decisions, nor can we claim superior knowledge of their business. In brief, we don't need power over them! Seeking it is actually counter-productive to our goal of creating a more free software ecosystem.

Hence, we have no obligation nor need to eradicate Windows in the marketplace nor to consume marketshare. That's because we aren't a massive multi-national corporation which must exercise power over people in order to survive. Marketshare: defined either as sales of services or as total numbers of installations is a nice sign of success for GNU/Linux, but it is in no way essential to the end goal of achieving freedom.

Self-reliance

Freedom is primarily achieved by providing the means for self-reliance. When individuals can provide for their own needs independently, without placing burdens on others, they are more free.

Freedom is primarily achieved by providing the means for self-reliance

GNU/Linux provides self-reliance in the form of software you have complete control over. Instead of having to pay a tribute in order to receive a benefit from a corporate provider, you are able to provide for your own needs using a freely-available product. In practice, of course, you really do this through voluntary sharing networks or "the community" of open source users and developers, rather than trying to operate on your own. However, you are by no means required to participate in this community, and of course, there may very well be more than one such community if one is not universally appealing (as a simple example, there are lots of Linux user groups divided by geography or language).

What does matter: sharing and standards

So what makes you free to choose free software? Essentially, what you need are quality and stability. There is also the touchier matter of interchangeable data format standards. To explain these criteria, let's consider the reasons you might be un-able to use a free software application to do a job:

- Software crashes due to bugs (quality)

- Software is too out of date (stability)

- Can't open the files (data standards)

The first two problems have nothing to do with marketshare for free software programs. They have to do with the level of development activity: How many different platforms and configurations has the software been tested in; how many people are finding bugs; and how much time is being spent on fixing them once they are found?

All of these have to do not with the percentage of people merely using the software in the marketplace, but with the absolute number of people developing and testing the program. In other words, a niche program that less than 1% of the public is using, but which has a strong, highly-motivated group of developers and users may be more successful than a package which is used by 99% of the population, but has few people interested in keeping it working (of course, it's unlikely that such a popular program would not find dedicated users, but this is by no means a closely-correlated relationship).

what matters is the people who are sharing their time to work on the project

In other words, what matters is the people who are sharing their time to work on the project. And that is enabled by the nature of the license, which allows the software itself to be shared. In other words, the strength providing the quality and stability of free software comes from the sharing of community effort and of the software itself. Marketshare, as such, has a limited impact on this for free software (the major exception is when a company makes significant money from the product and therefore decides to share developer time to work on it—but again, there is no strong correlation here: a company is free to free-ride or contribute, regardless of its income from the software).

So why do people quote marketshare as if it were the absolute most important metric? Because, for proprietary software it is: if only 1% of the public buys licenses for software A, but 99% buy licenses for software B, then B has 99 times as much money to pay developers. And that's really important for proprietary development projects, because they don't share. By not sharing the code, they not only discourage the desire to share effort, but they actually make it much more difficult (or even impossible) to do. As such, all development and testing time on proprietary software must be paid for. Thus, it is the availability of funds, driven entirely by marketshare, that determines the quality and stability of proprietary software. That's why it's sensible for proprietary software developers to quote marketshare as a selling point.

But those rules don't apply to free software—it relies on voluntary sharing to achieve the same ends. And it turns out that that is much more cost-effective.

The third item, data standards, does have a connection to marketshare, albeit it a tenuous one. If a single supplier wields effective monopoly control of the marketplace, it can also monopolize the formats of data that are used for communications. For example, when Microsoft had such total domination of the word processing marketplace, it created a situation in which a proprietary data format—MS Word DOC format—became a de facto interchange standard. Since this format was secret and only fully supported by MS Word, it created an obstacle to people wanting to use free software. A similar situation exists with respect to various DRM encrypted file formats and video codecs used today.

If a single supplier wields effective monopoly control of the marketplace, it can also monopolize the formats of data that are used for communications

Avoiding monopolies

These are openly hostile attacks on market freedom by those companies. They are, as the law puts it, "anti-competitive", because they put competitors at an unfair disadvantage. This creates a situation in which quality is not sufficient to allow a product to be used. It isn't just free software that suffers from this! This is a problem for all competing software.

Thus, in the interest of promoting both freedom and market efficiency, such tactics, whether intentional or not, should not be permitted. This can be achieved through legal means, primarily by not granting monopoly copyright nor trade secrecy protections for such standards. It can also be achieved by social movements to use standards which are freely available. Finally, having more than one effective competitor in the marketplace will result in natural market forces to encourage use of open formats.

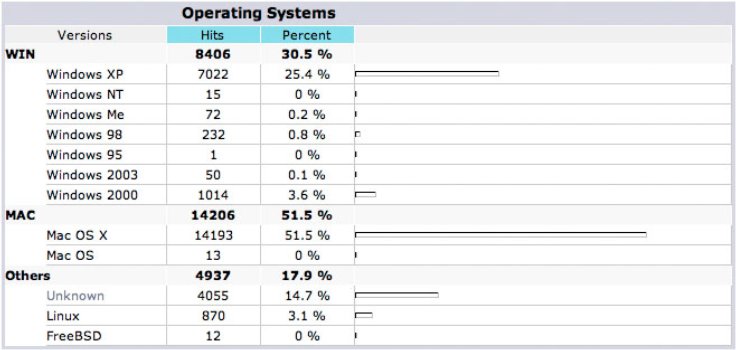

However, even where marketshare matters, it matters only in the need to avoid extreme monopoly: it is not that GNU/Linux needs to have a 90% or even a 50% marketshare to be a "success", it is only that allowing one other software (Microsoft Windows) to have a 90% or 99% marketshare is damaging. A 10% or 15% share of the marketplace would be completely sufficient. More importantly, that 10% or 15% needn't belong to GNU/Linux—it just can't belong to Microsoft (or any other single provider). We're perfectly fine if that marketshare is controlled by Apple's OS X or Free BSD, or some other operating system, so long as it really is independent of Microsoft control.

Success for free software is having the freedom to use it

This is a very different situation than with proprietary software, where "success" is directly proportional to marketshare (or absolute market size). In the end, for the cause of freedom, we don't need a strong marketshare. We just need a free market and enough sharing to get the software developed.

Of course, freedom may not be everyone's goal for free software. Some people may simply want market domination, and there are companies like Canonical (maker of Ubuntu) who will benefit from increased adoption of GNU/Linux. Their financial successes—at whatever level—are beneficial to the overall success of GNU/Linux, because they mean that more money will be spent on developing GNU/Linux. However, even if such companies fail, GNU/Linux will not: development will continue whether there is financial backing from sales of services or not, so long as there are enough people who need the software enough to share their time in keeping it working and providing new capabilities.